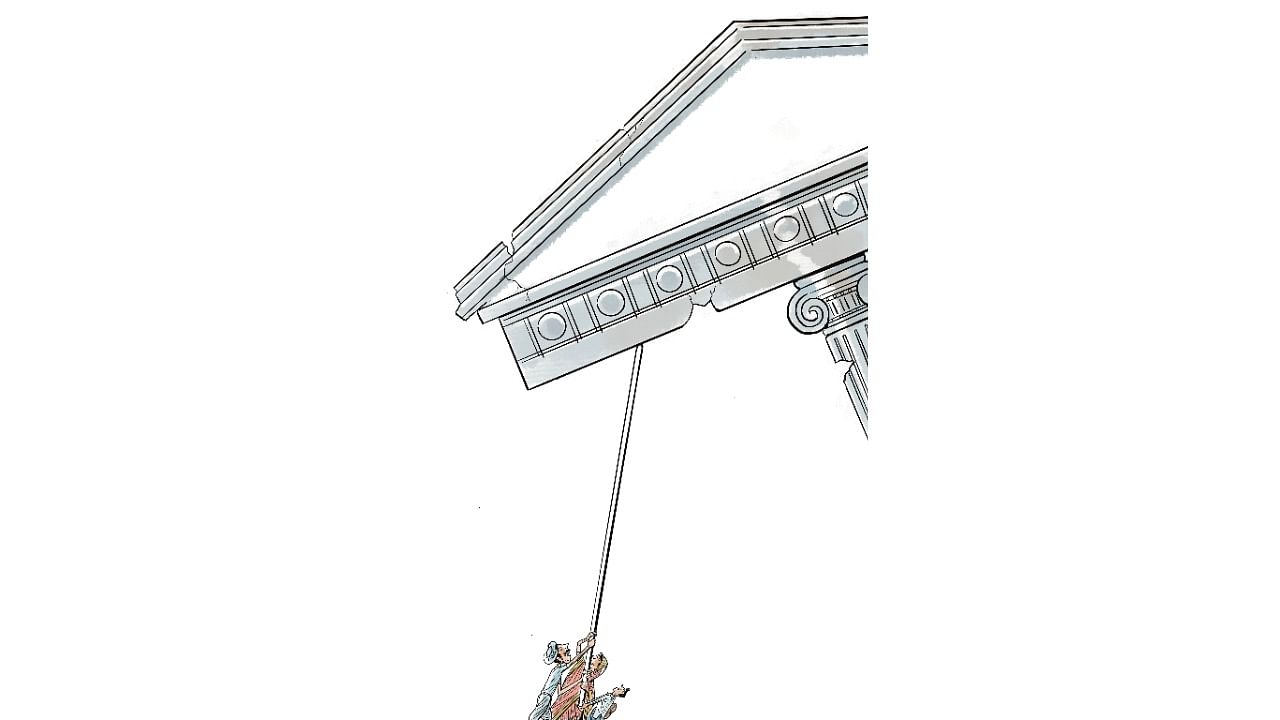

Hope floats...

Credit: Dh Illustration

The turn of the second millennium had appeared promising for democracy. More people than ever before lived under governments that committed to involve them in running the affairs of their country. Elections, freedom of association and expression, and the rule of law were guaranteed — at least on paper — by these governments as a gesture towards recognising their populations’ political rights. Authoritarian governments — China, Saudi Arabia, Belarus — appeared to be anomalies: anachronistic regimes that had somehow survived the test of time but whose time was up. Democracy was here to stay, we were told, as all other forms of government stood discredited.

A stark contrast

Two decades on, the contrast cannot be starker. Democracies everywhere are mired in crisis. In some cases, democratic gains made at the close of the 20th century face outright reversal: think about Russia and Venezuela. In others, countries transitioning from authoritarianism don’t quite seem to make it to democracy and are stuck in what one political analyst called a “grey zone”: Central Asian successor states to the Soviet Union fall under this category.

A third source of crisis in democracies stems from their inability to deliver basic services: democracies in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa have long been in this category of difficult democracies. Yet another cause of worry for democracies stems from their inability to contain economic volatility that is fundamentally ingrained in capitalism: while the world is richer than ever before, ever fewer people share in its income and wealth. To be sure, democracies do not cause economic troubles but they appear unable to contain such troubles when they occur, fomenting discontent.

A final source of anxiety for democracy is far more insidious. Countries that have retained the shell of democracy but have hollowed it out of any substance. Here, one is not talking about entities such as the self-styled Democratic People’s Republic of Korea whose authoritarian character is plain to any observer.

Their claims to being a democracy are so patently ridiculous that no reasonable observer would characterise them as one.

Rather than such obviously authoritarian examples, consider countries where rituals associated with democracy are routinely followed, but the substantive practice of democracy is barely respected. Examples that spring to mind include Turkey, Hungary, Brazil, the Philippines, South Africa, the USA and India where elections are routinely conducted and their verdicts respected.

In the name of the people

Politicians seek power in the name of the people. In other words, power is legitimated in people’s names. However, electoral mandates are interpreted as enabling those in power to do as they please, all in the name of the people. Once in power, politicians treat rivals as enemies. The press is muzzled. Dissent is stifled. Courts are co-opted. Bureaucracies are bent to the whims of those in power. Liberals and leftists often find themselves at the receiving end of politicians’ attacks while immigrants make for easy scapegoats. Any criticism of the government is condemned as a criticism of the nation, and worse, as a criticism of the people in whose name politicians rule.

In a subset of these countries, furthermore, the idea of “the people” takes on quite exclusive forms. A supremacist ethic is nurtured. Members of specific social groups are constructed as core to the nation. Others are identified as marginal or peripheral to it. They are regarded as alien to the nation and even dangerous to it. The basis of this distinction varies.

It could be racial, as in the USA under Donald Trump when its white population was identified as core to the country’s nationhood. Alternatively, it could be religious as in Turkey, Brazil (till 2020) and India where Recep Erdogan, Jair Bolsanaro and Narendra Modi respectively upheld their countries’ Muslim, Christian and Hindu religious identities to the exclusion of others. Critics of the government find themselves branded not only as enemies of the people but also as enemies of the majority religion professed by their countrymen.

The case for according respect

Democracy is often thought to mean the mere conduct of routine elections. Sometimes it is confused with imposing the will of the majority. But it means so much more than elections and the will of the majority. Democracy is, more importantly, a social process in which people can assert their equality before one another and before the law. Democracy is about treating people, even political adversaries, with respect. It is about affording dignity to people, irrespective of their social backgrounds and political opinions. Democracy welcomes, rather than stifles, dissent. These trends are evident worldwide.

Reasons for democratic breakdowns vary. In many cases, democracy is unable to contain inequality. So those who find themselves economically and socially marginalised support authoritarian rulers who promise against “elites”: this seems to explain the support for Donald Trump and Recep Erdogan from among the poorest parts of their countries. Elsewhere, democracy is unable to accelerate economic growth.

Democratic governments seek to include diverse social constituencies in attaining economic growth fomenting resentment among elites: this could explain the support for Narendra Modi and Jair Bolsanaro in among the richest parts of their respective countries.

Across the board, groups that fear a loss of social status, such as Whites in the USA, observant Muslims in Turkey, and “upper-caste” Hindus in India grow suspicious of what they would consider “too much democracy.”

Lessons from history

There was a time when we associated a crisis in democracy with spectacular events. Men in jackboots parading public squares, armed folks storming homes or offices of politicians and arresting them, abrupt suspensions of normal broadcasts that announced the suspension of democracy: these images came to mind when we heard about democracy in crisis.

Often, it was the military that overthrew elected politicians on grounds of incompetence, corruption or ideological deviance. Sometimes, elected politicians themselves suspended democracy citing internal disturbance or foreign aggression. A single event defined democratic breakdown.

Take Pakistan. In the wee hours of July 5, 1977, Pakistan’s elected Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto found himself under arrest. The Pakistani army, under General Zia ul-Haq, was taking over the country. General Zia promised to hold elections within three months.

He even released Bhutto so he could campaign. However, he changed his mind upon seeing Bhutto’s popularity. Bhutto was arrested again. Elections were postponed. Legal charges were brought against the former Prime Minister. An elaborate trial lasting almost eighteen months was staged. Bhutto was found guilty and hanged. Pakistan’s democracy had been strangled to death.

Military generals are not the only ones who have annihilated democracy. Elected politicians too have been culpable. Like the generals, they too have cited a combination of internal disturbances, social unrest, economic crisis and political uncertainty to suspend democratic principles and practices.

On March 23, 1933, Adolf Hitler persuaded fellow parliamentarians in Germany’s Reichstag to pass the Enabling Act. His party had emerged as the single largest party in the elections held earlier that month but fell far short of a majority. Although appointed Chancellor, Hitler’s Nazi party found itself hamstrung by coalition partners and a variety of opposition parties. The Enabling Act freed Hitler from these constraints. It gave him the right to pass laws without the Reichstag’s approval for the next four years, effectively destroying all institutional opposition to Hitler’s rule. The Reichstag barely met during the remainder of Hitler’s rule.

Many triggers

A few minutes before the clock struck midnight on June 26, 1975, a state of Emergency was proclaimed across India. Unlike Hitler, India’s Indira Gandhi had decisively won a national election three years prior, on the back of a crushing military victory against arch-rival Pakistan.

That did not prevent her from suspending India’s parliament. Opposition leaders were jailed. Elections were cancelled. Civil rights were suspended. State legislatures were dissolved. Gandhi appropriated all power and ruled by decree, advised by a coterie that included her younger son. Throughout the nineteen months of the Emergency, democracy in India gasped for breath.

Democratic breakdowns may be triggered by the disenfranchisement of some sections of the national population.

Such disenfranchisement could be initiated by military rulers: Myanmar’s 1982 Citizenship law which effectively stripped that country’s Rohingya minority of their citizenship comes to mind.

However, it is not only authoritarian rulers who divide their populations thus. Elected politicians have been just as culpable, if not more.

The spirit of South Africa’s Apartheid legislation resonated with the Jim Crow laws that segregated racial groups in the United States of America (USA). These laws were introduced by elected politicians across the southern States of the USA in the aftermath of the Civil War. Several US States — in the South but also the North — continued to pursue policies of racial segregation through most of the 20th century. Despite its proclamations of freedom, the USA was a democracy only in name till the civil rights movement compelled the dismantling of segregation laws after 1965.

Hopelessness is a luxury

That said, no autocrat is ever unchallenged. Often, such challenges are mounted by ordinary people who appear weak, meek and powerless in the first instance. Their challenges may not always be successful. Indeed, they may be utter failures in changing the regime. But they show the continued importance of hope, as every autocrat in history, discovered.

Indeed, as the last decade has shown us, Indians are not letting their democracy quietly slip away without putting up a good fight. The actions of countless Indians — ranging from farmers to students, politicians to artistes, social activists, and daily wage labourers — show the many ways in which they are resisting the onslaught on their freedom. Their immense courage and fortitude warn observers that fixating on democracy’s collapse in India (or anywhere else for that matter) is not only counter-productive but extremely unfair to their increasingly desperate attempts at salvaging their democracy. To say that there is no hope for democracy’s survival in India is to mirror the actions of those who seek to strangle it. Hopelessness is a luxury no Indian who cares about their democracy can afford.

(The writer is a Professor of Global Development Politics in the Department of Politics and International Relations at the University of York. He specialises in the study of Indian politics from comparative and historical perspectives. He has recently authored Audacious Hope: An Archive Of How Democracy Is Being Saved In India, published by Westland.)