For example, while conceptually the debt must be low enough such that government revenues (from oil or tax revenues, for example) must be able to service payments on the debt, the question still remains as to why Japan is able to service a debt of over 200% of GDP, while Greece buckled with a similar debt-GDP ratio?

And that is just one illustrative example of the nuances of public debt. Among economists, there are those that are deficit hawks, and others who believe if the debt were held in the domestic currency, it doesn’t really matter to a certain extent, since the government has the power to pay off the debt by printing money. Of course, that may have other consequences, but the immediate consequence is that the debt can be serviced.

In India, Parliament has passed the fiscal responsibility and budget management Act, giving targets for the fiscal deficit. But why was that necessary? What was going wrong before the Act was passed that made it necessary? One way to frame the question here is by asking whether India can also sustain a debt like Japan’s and, even if the capacity exists, whether it is even desirable to maintain such a debt.

Of course, at some point, this is a moral question – that of whether it is fair for the current generation of politicians to burden future generations with the burden of debt. Perhaps this is the primary purpose of the FRBM Act – that is, to safeguard future governments from being laden with debt from present governments.

None of this is to deny that fiscal responsibility of some kind is necessary for growth, particularly in a modern capitalist economy. A high fiscal deficit, depending on how it is financed, either crowds out private investment at times of high capacity utilisation or leads to inflation if financed by monetising the debt.

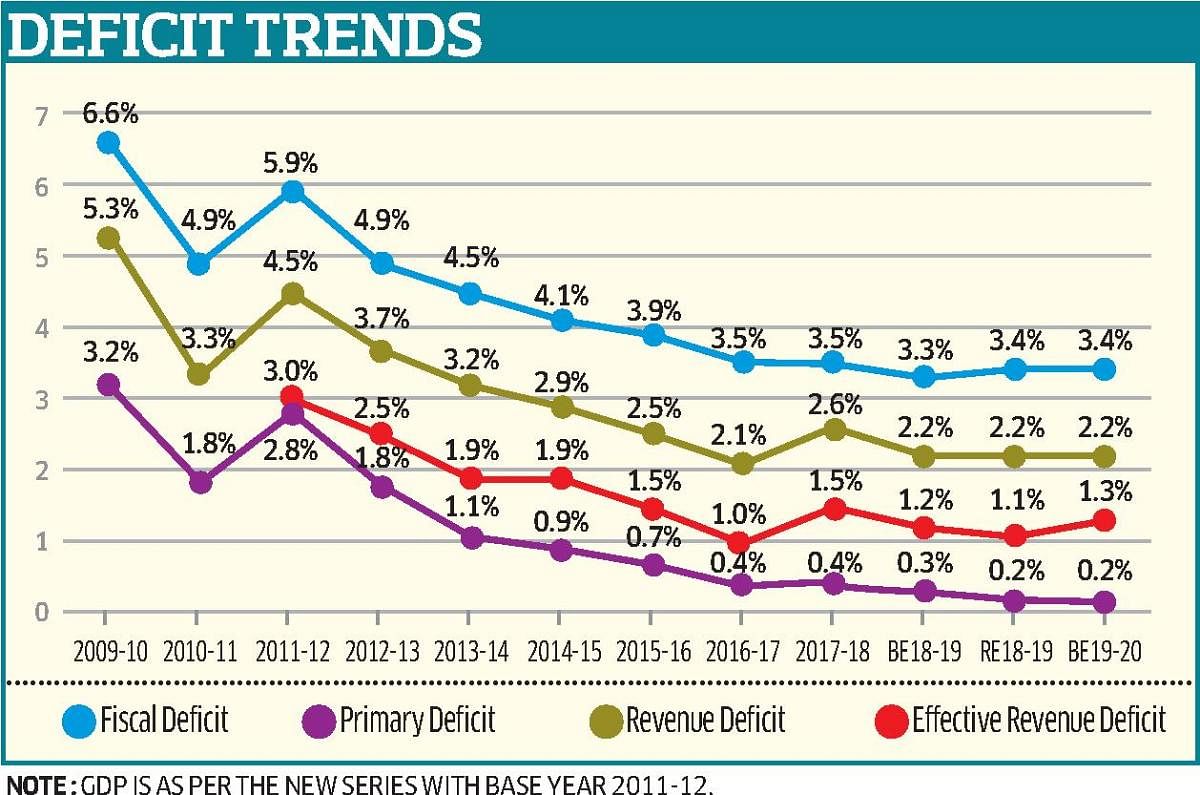

However, as advanced economies like Japan have experimented with fiscal deficits as high as 8%, it is unclear whether the danger line starts at 3% as the FRBM Act stipulates as the maximum.

Indeed, it seems like the aim of the FRBM Act was simply to reduce the debt burden without much regard to the question of why it is desirable. Of course, rating agencies are another factor in the equation here. Rating agencies typically use their own logic – not necessarily sound logic one might add – to upgrade and downgrade sovereign debt, thereby making it easier and cheaper for a fiscally prudent government to borrow. The question then becomes whether one wants to be held at the mercy of rating agencies or follow an independent path.

The conclusion one can draw from this is that various strategies have been tried the world over, ranging from a balanced budget to high budget deficits and high public debt. To take an example frequently cited in this article, in the case of Japan, the high public debt came about due to repeated fiscal stimulus packages in a time of inadequate demand in the 90s.

It is debatable whether the strategy worked, but nonetheless, it was still a conscious decision taken by a sovereign state to increase its national debt, albeit in a time of underemployment and capacity underutilisation.

Therefore, it is possible to have a strategy different from the one laid out in the FRBM Act which is to reduce public debt to 40% of GDP and the fiscal deficit to 3%, which seems, therefore, to be somewhat though not wholly arbitrary.

Finally, ideology undoubtedly plays a role in your preference for low or large fiscal deficits. While staying within the bounds of sustainability of the debt, it is possible to have a preference for larger or smaller deficits. Small government and free enterprise proponents would naturally gravitate towards smaller fiscal deficits on the grounds that smaller fiscal deficits lead to increased private investment and a larger space in the economy for a private business while socialists would prefer larger fiscal deficits to fund welfare schemes and public investment.

There is, however, a large body of consensus within the Keynesian tradition of economics that in times of recessions or depressions, larger fiscal deficits do not crowd out private investments and are necessary to stimulate the economy.Given this fact and given the fact that reasonable people may disagree on the optimal quantum of fiscal deficits, it is somewhat strange that the government has decided to tie its own hands, and the hands of future governments, as to the fiscal space available to it in order to implement welfare schemes and stimulate the economy in times of crisis.