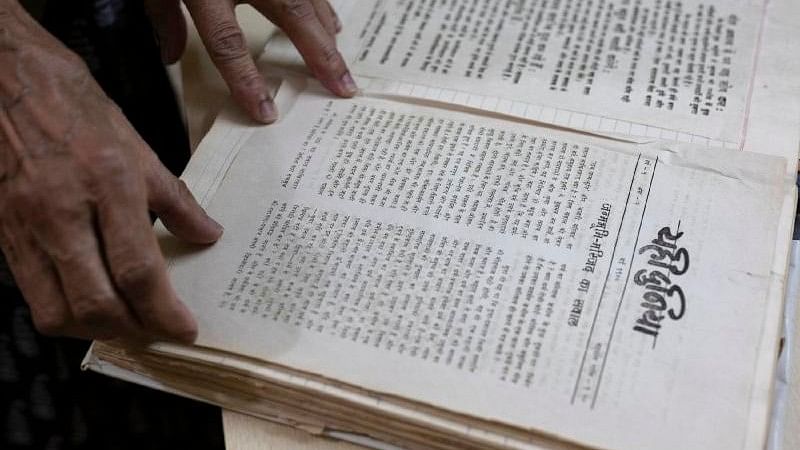

The use of posters and pamphlets to raise public awareness is a time-tested practice among Indian activists.

Credit: International New York Times

Lucknow: One recent morning, Roop Rekha Verma, an 80-year-old peace activist and former university leader, walked through a neighborhood prone to sectarian strife and parked herself near a tea shop.

From her sling bag, she pulled out a bundle of pamphlets bearing messages of religious tolerance and mutual coexistence and began handing them to passersby.

“Talk to each other. Don’t let anyone divide you,” one read in Hindi.

Spreading those simple words is an act of bravery in today’s India.

Verma and others like her are waging a lonely battle against a tide of hatred and bigotry increasingly normalized by India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party, or BJP.

As Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his deputies have vilified the country’s minorities in a yearslong campaign that has escalated during the current national election, the small band of ageing activists has built bridges and preached harmony between religious groups.

They have continued to hit the pavement even as the price for dissent and free speech has become high, trying to keep the flame alive for the nonsectarian ideal embedded in India’s Constitution and in their own memories.

More than three dozen human rights defenders, poets, journalists and opposition politicians face charges, including under anti-terrorism laws, for criticizing Modi’s divisive policies, according to rights groups. (The government has said little about the charges, other than repeating its line that the law takes its own course.)

The crackdown has had a chilling effect on many Indians.

“That is where the role of these civil society activists becomes more important,” said Meenakshi Ganguly, a deputy director at Human Rights Watch. “Despite a crackdown, they are refusing to cow down, leading them to hold placards, distributing flyers, to revive a message that once was taken for granted.”

The use of posters and pamphlets to raise public awareness is a time-tested practice among Indian activists. Revolutionaries fighting for independence from British colonisers employed them to drum up support and mobilise ordinary Indians. Today, village leaders use them to spread awareness about health and other government programs.

Such old-school outreach may seem quixotic in the digital age. Every day, India’s social media spaces, reaching hundreds of millions of people, are inundated with anti-Muslim vitriol promoted by the BJP and its associated right-wing organizations.

During the national election that ends next week, Modi and his party have targeted Muslims directly, by name, with brazen attacks both online and in campaign speeches. (The BJP rejects accusations that it discriminates against Muslims, noting that government welfare programs under its supervision assist all Indians equally.)

Those who have worked in places torn apart by sectarian violence say polarisation can be combated only by going to people on the streets and making them understand its dangers. Merely showing up can help.

For Verma, the seeds of her activism were planted during her childhood, when she listened to horror stories of the sectarian violence that left hundreds of thousands dead during the partition of the Indian subcontinent in 1947.

Later, as a university philosophy professor, she fought caste discrimination and religious divides both inside and outside the classroom. She opposed patriarchal attitudes even as slurs were thrown at her. In the early 1980s, when she noticed that the names of mothers were excluded from student admission forms, she pressed for their inclusion and won.

But more than anything else, it was the campaign to build a major Hindu temple in the town of Ayodhya in her home state of Uttar Pradesh that gave Verma’s life a new meaning.

In 1992, a Hindu mob demolished a centuries-old mosque there, claiming that the site had previously held a Hindu temple. Deadly riots followed. This past January, three decades later, the Ayodhya temple opened, inaugurated by Modi.

It was a significant victory for a Hindu nationalist movement whose maligning and marginalizing of Muslims is exactly what Verma has devoted herself to opposing.

The Hindu majority, she said, has a responsibility to protect minorities, “not become complicit in their demonization.”

While the government’s incitement of religious enmity is new in India, the sectarian divisions themselves are not. One activist, Vipin Kumar Tripathi, 76, a former physics professor at the prestigious Indian Institute of Technology in New Delhi, said he had started gathering students after classes and educating them about the dangers of “religious radicalization” in the early 1990s.

Today, Tripathi travels to different parts of India with a message of peace.

Recently, he stood in a corner of a busy train station in northeastern New Delhi. As office workers, students and laborers ran toward platforms, he handed information sheets and brochures to anyone who extended a hand.

His materials addressed some of the most provocative issues in India: the troubles in Kashmir, where the Modi government has rescinded the majority-Muslim region’s semiautonomy; the politics over the Ayodhya temple; and ordinary citizens’ rights to question their government.

“To respect God and to pretend to do that for votes are two different things,” read one of his handouts.

At the station, Anirudh Saxena, a tall man in his early 30s with a pencil mustache, stopped and looked Tripathi straight in the eyes.

“Sir, why are you doing this every week?” Saxena asked.

“Read this,” Tripathi told Saxena, handing him a small 10-page booklet. “This explains why we should read books and understand history instead of reading WhatsApp garbage and extracting pleasure out of someone’s pain.”

Saxena smiled, nodded his head and put the booklet in his handbag before disappearing into the crowd.

If just 10 out of 1,000 people read his materials, Tripathi said, his job is done. “When truth becomes the casualty, you can only fight it on the streets,” he said.

Shabnam Hashmi, 66, another activist based in New Delhi, said she had helped distribute about 4 million pamphlets in the state of Gujarat after sectarian riots there in 2002. More than 1,000 people, most of them Muslims, died in the communal violence, which happened under the watch of Modi, who was the state’s top leader at the time.

During that period, she and her colleagues were harassed by right-wing activists, who threw stones at her and filed police complaints.

In 2016, months after Modi became prime minister, the government prohibited foreign funding for her organization. She has continued her street activism nonetheless.

“It is the most effective way of reaching the people directly,” she said. “What it does is, it somehow gives people courage to fight fear and keep resisting.”

“We might not be able to stop this craziness,” she added, “but that doesn’t mean we should stop fighting.”

Even before Modi’s rise, said Verma, the activist in Uttar Pradesh, governments never “showered roses” on her when she was doing things like leading marches and bringing together warring factions after flare-ups of religious violence.

Over the decades, she has been threatened with prison and bundled into police vehicles.

“But it was never so bad,” she said, as it has now become under Modi.

The space for activism may completely vanish, Verma said, as his party becomes increasingly intolerant of any scrutiny.

For now, she said, activists “are, sadly, just giving proof of our existence: that we may be demoralized, but we are still alive. Otherwise, hatred has seeped so deep it will take decades to rebuild trust.”