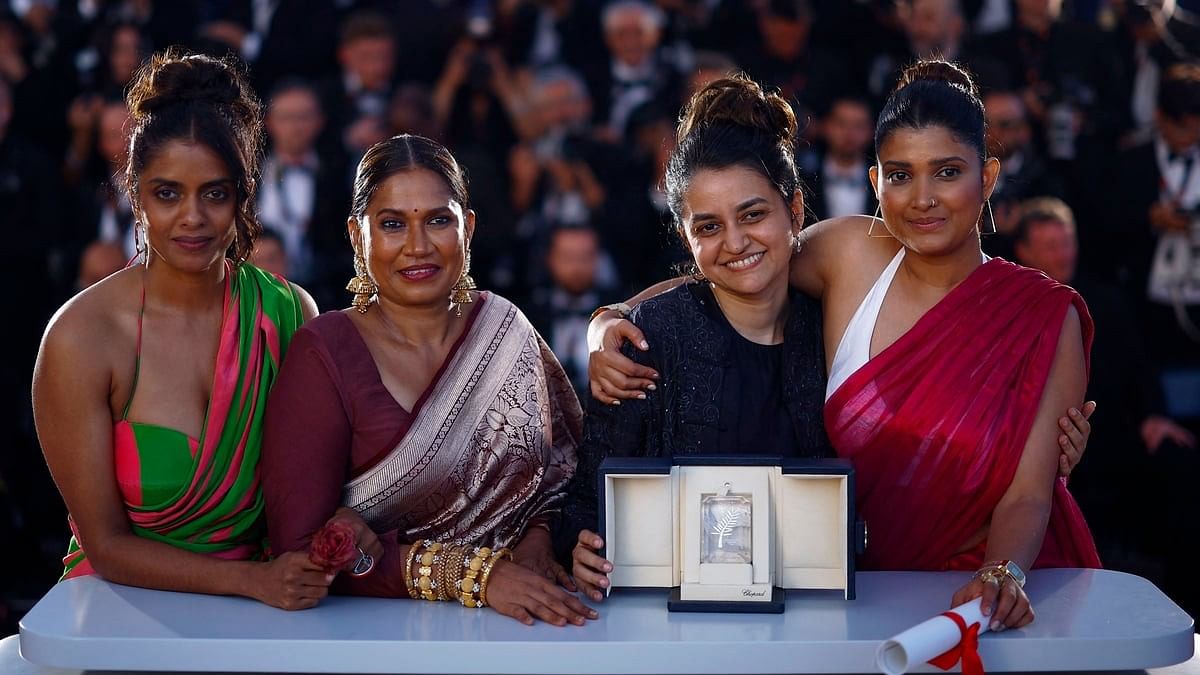

Director Payal Kapadia, Grand Prix award winner for the film "All We Imagine as Light" poses with cast members Divya Prabha, Kani Kusruti and Chhaya Kadam during a photocall after the closing ceremony of the 77th Cannes Film Festival in Cannes, France.

Credit: Reuters Photo

It was a dreary beginning at the competition section of the Cannes Film Festival this year. Despite their grand entry on the red carpet and a standing ovation at the end of the screenings, the likes of Francis Ford Coppala, David Cronenberg, Paul Shrader and Ali Abbasi were all disappointing in their latest works. It was a mere celebration of their reputation.

It was not enough to enthuse the discerning audiences at the Theatre Grand Lumiere where cineastes gather in large numbers to access contemporary world cinema. Even the better ones of the lot by eminent Greek director Yorgos Lanthimos, Chinese director Jia Zhangke, French realisateur Jacques Audiard and the Italian master Paolo Sorrentino were all patchy and inconsistent. The redeeming features were found only in other sections like Un Certain Regard, Critics Week and Directors Fortnight. In those were small independent films like the French ‘L’Histoire the Souleymane’, the Chinese ‘Black Dog’, the Italian film ‘The Damned’, Bulgarian film ‘The Shameless’ and the first Saudi Arabian film ‘Norah’ among a few others.

Amidst all this, in the last two days of the event, the young Indian filmmaker Payal Kapadia brightened up the proceedings with her debut feature film ‘All We Imagine As Light’. She was joined by Miguel Gomes, the Portuguese filmmaker with his classical film ‘Grand Tour’ and the celebrated Iranian director and political dissenter in exile Mohammad Rasoulof, with ‘The Seed of the Sacred Fig’. His film, along with Payal’s restored the credibility of the competition section. The festival was back on track by the last day.

The context under which Rasoulof appeared at the festival forum escaping imprisonment in Iran added to the democratic spirit of the festival. The Cannes festival is known for its celebration of life and artistic freedom. Recognising these films in the face of stiff competition from big filmmakers escalated the festival’s value.

Though Sean Baker’s ‘Anora’ (from the US) won the top prize at the event, it was Kapadia and Rasoulof who stole the show. The overwhelming media attention and positive critical response to the films of the two filmmakers from Asia not only shifted the limelight to artistic expressions of the region but also underlined the socio-political realities that shape contemporary arts and cinema in particular.

The Best Actress award to a non-celebrity Indian actor Anasuya Sengupta in the Un Certain Regard section of the festival — in a film with Indian content by a Bulgarian auteur — and the Best Student Film award conferred on Dr Chidananda Naik, a Film and Television Institute of India student from Mysuru are also proof of the arrival of a new generation of film artistes from the Indian subcontinent.

What ‘All We Imagine As Light’, which won the Grand Prix (second highest awards at the festival), does is historically significant. It decodes the western sensibilities in a way the eminent filmmaker Satyajit Ray did with his early films in the last century. Almost all the western critics invoked his name in their reviews of Payal’s film. If Peter Bradshaw of the UK-based newspaper Guardian described it as “glorious, fluent and absorbing story full of humanity,” Indiewire critic Sophie Monk Kauffman highlighted the vignettes of sensuality and rhythm of life the film casually uncovers in its narrative.

However, one need not be carried away by these expressions of western adoration and sensibilities. Payal’s film does really project an Indian identity in a sea of films in the Indian marketplace though it is not known whether it has a separate Indian title. The film demands and deserves acceptance of the global movie scene of new Indian form of independent film makers.

‘All We Imagine As Light’ goes beyond the social realism genre of the Indian independent cinema vibrant mostly in regional films. It also places Indian reality in a universal context and explores both the social reality of the external world and the inner conflicts of the soul of India. It paradigmatically shifts the film form of Indian realist cinema from the shadows of the school of Italian Neorealism to its own post colonial search for a new film theory and practice. This had become evident in Indian indie cinema’s recent past. Some film critics even invoked the contribution of the eminent filmmaker Wong Kar Wai to mainland Chinese cinema in juxtaposing the proletarian concerns of the needs of the body and bourgeois spiritual search and how portraying the body and mind are integrated into the narration of a film.

If the Palme D’Or award winning film ‘Anora’ indulges in bold images of sensual and erotic search of the human body, Payal’s film balances the needs of the body and the mind in a calm and stoic way. It demands from the audience a greater understanding of hope in an illusory life of contemporary Indian reality. It does not evade any issues of that reality. The reality of deprivation, political agendas of organised religions and patriarchy, economic clichés of development and consumerism is evident. But then there is an intellectual and philosophical tone to it as well. When one of the characters exclaims that life in the metropolis (Mumbai) is not a dream but an illusion, it is a philosophical statement rather than a response to the clichéd expression for Mumbaikars resilience in the face of adversity, both natural and man made.

It is this philosophical assertion of the film and it’s efficient film making techniques that pushed out of competition Coppola’s ‘Megalopolis’, a story of overindulgent and narcissistic notion of the cities of the world, David Cronenberg’s weird and unimpactful futuristic tale ‘Shrouds’ and the self effacing drama of Paul Schrader ‘Oh Canada’.

The banal autobiographical works on the maverick former president of US Donald Trump, the Punk writer and Russian anarchist Eduard Limonov and the light hearted pointless replication of legendary Italian actor Marcello Mastroianni’s life faded into oblivion in the context of social impact of ‘All We Imagine As Light’ and ‘The Seed of the Sacred Fig’.

Despite the excessive marketing and commodification of cinema and parading celebrities on the over publicised red carpet, the core of the festival still remains strong. Though the western sensibilities are still averse to the emotionally driven stylistically performed cinemas of the east, the realities cannot be overlooked. Thus the festival had to include more cultures and forms. Films like ‘All we Imagine as Light’ demands inclusivity.

The film also brings to notice the aspiring young Indian filmmakers, the nature of film production and distribution in today’s movie business. It has in its title credits, production houses from France, Netherlands, Luxembourg and India as producing partners. This is the reality of almost all the films in the competition section of the festival. This indicates that art of the cinema can survive only through international cooperation and multilateral economic resources but that is another story ‘All we Imagine as Light’ is trying to convey.