In a scene in Gulzar’s ‘Mere Apne’ (1971), a group of unemployed youth are tasked with canvassing for a local politician in an upcoming election. He assures amazing guarantees to these young men hoping they’d galvanise sufficient support for him. “Mere pinjre ka panchchi jeet jaaye,” he tells them referring to his poll symbol — a caged bird. An apt symbol, the group’s leader jokes, hinting at the lofty promises political candidates make to entice the public. The politician laughs and in fake modesty calls his life in politics a bondage he’s unable to escape — “Ek pinjre ka panchchi.”

This is one of the few instances in Hindi cinema where a filmmaker refers to an election symbol. In our films, election symbols have typically appeared as background props, even in the ones with political themes and characters. They’re used arbitrarily with no connection or impact on the story. Flora, fauna, and fowls are the most commonly deployed ones — a banyan tree in ‘Hu Tu Tu’ (1999), a rose in ‘Satta’ (2003) and ‘Shorgul’ (2016), sugarcane and peacock in ‘Fukrey 3’ (2023) to name a few. In other instances, there are inanimate objects: a remote control (‘Gulaab Gang’, 2014), a boat (‘Jallaad’, 1995), and even a liquor bottle (‘Mard’, 1998). The symbols and slogans of real political parties are also common background sights, often clashing with fictitious ones. Additionally, when they are unable to use the real ones, films inspired by political events (‘Bombay’, 1995; ‘Satyagraha’, 2013) and figures (‘Thalaivii’, 2021) try to use party symbols as creatively as possible to make them seem similar.

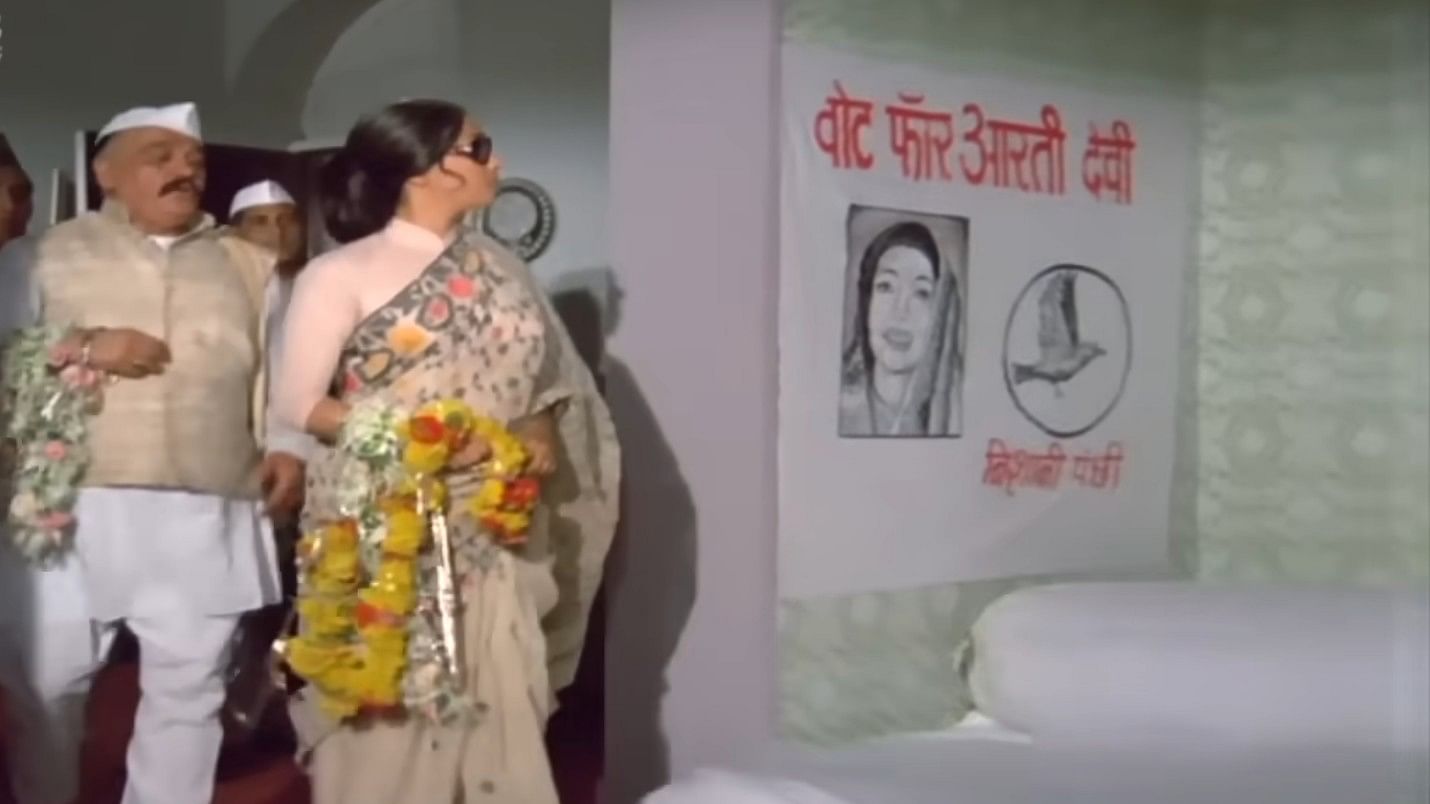

On occasions where these electoral emblems are purposefully used on screen, they’ve served as effective metaphors. In ‘Aandhi’ (1975), Gulzar’s other important work with a political backdrop, the heroine’s introduction as a high-aiming, hard-nosed leader is done with her election symbol: a flying bird. Her political opponent sees her as a ‘helicopter candidate’ and uses a lantern to symbolise his austerity. Similarly, a rising sun signifies the growing stature of a young, popular leader in ‘Raajneeti’ (2010).

Sometimes these symbols are woven into the narrative for relevance. In ‘Ishaqzaade’ (2012), an intense election battle is vital to the central love story of the scions of two rival political families of different faiths. The heroine leads a spirited campaign for her father, the incumbent. Highlighting the technological advancements her father has brought about in their constituency, she points at the aptness of his election symbol: a computer. The hero canvasses for his political heavyweight grandfather whose emblem is a cell phone. In ‘Dasvi’ (2022), a wily, semi-literate politician forced to pursue an education, discovers its transformative power and the true meaning of public service. His newly floated party’s symbol, a pencil, is dedicated to this new learning. The irony isn’t lost on anyone that ‘Gangs of Wasseypur’’s (2012) ruthlessly exploitative coal mafia boss forays into politics with a miner’s pickaxe as his symbol to appear relatable.

The egalitarian porter hero from Manmohan Desai’s ‘Coolie’ (1983) uses his fabulous feathered friend Allah Rakha (a hawk) as his poll symbol. Pitted against him is a shrewd industrialist (played by Kader Khan) who isn’t above using unscrupulous means to win an election. His flaming torch accompanied by an inspiring slogan ‘Gareebi ka andhera hataao, mashaal pe mohar lagaao’ for his blue-collar voters is mere lip service.

Remarkably, in Khan’s other films dealing with politics too, the party symbols always had an interesting bearing. As he’s often the dialogue writer in them, Khan’s signature wit and humour shine through. Most famously in ‘Inquilaab’ (1984) where a political party comprising crooks, dishonest politicians, and wealthy businessmen is ironically named Gareebon Ki Party with an impoverished family as its symbol.

In other cases, these symbols became a tool for socio-political commentary. The corrupt and self-seeking side of politics is explored in Rajesh Khanna-led satire ‘Aaj Ka M.L.A Ram Avtar’ (1984). As several ideologically disparate political parties band together to form ‘Akhil Bhartiya Bahurupi Sangath’, their supremo Ram Avtar proposes a trishul (trident) as their party logo. Putting aside its religious significance, the three prongs would represent the basic issues of ‘roti, kapda aur makaan’, he suggests cunningly. The scene is a hat tip to the famous party meeting scene from ‘Kissaa Kursee Kaa’ (1978) — Amrit Nahata’s Emergency-era cult parody — which drew the ire of Congress leader and then prime minister Indira Gandhi’s son Sanjay, who infamously had the movie’s prints trashed. Here, a group of power-hungry people launch a new political outfit, ‘Kaali Party’. Satirising Indira’s famous slogan and Sanjay’s controversial ‘people’s car’ manufacturing project, they pick ‘Garibi Hatao’ as their slogan and a small car as their symbol.

The political signs of Dibakar Banerjee’s ‘Shanghai’ (2012) subtly add to its commentary. A dynamic, development-focused chief minister’s party has allied with a nationalist side to establish a special economic zone (SEZ) that threatens to displace marginalised locals. A frenzied election rally presents an unsettling picture of the might of capitalist forces and political self-interest. The symbolic dissonance between the growth-oriented CM’s party, represented by a sapling, and their jingoistic coalition partner’s “mukka nishaan” (a punch), underscores the opportunistic nature of the game. On the contrary, Mani Ratnam’s ‘Yuva’ (2004) that’s heavily focused on the youth’s participation in electoral politics and unfolds in Kolkata, a city renowned for its political consciousness, refrains from using any titles or symbols.

Capturing the minutiae of conducting a ‘free and fair’ election in an insurgency-affected remote village of central India, Amit Masurkar’s ‘Newton’ (2017) delivers the most profoundly incisive and empathetic view of the Indian electoral process and the electorate. In a telling scene, a uniformed officer patronisingly explains the EVM to petrified, perplexed villagers who are unaware of the voting procedure and have never seen any of the candidates before. They’ve simply been rounded up to make the polling look like a success. The machine is a toy with a bunch of symbols in it, he tells them. “Gaajar hai, motorcycle hai, jahaaz hai, jaanwar hai, phool hai, lota hai, NOTA hai… jo pasand aaye, button dabaa do.” A sobering realisation of the potential democracy holds and how distant and foreign it remains to its most vulnerable.