Even to someone who is deep into world cinema ‘KGF: Chapter 2’ is a difficult film to make sense of, given its incoherence. The same was true of the first chapter of ‘KGF’ but that film, ultimately meant less than this one since it was only about goons battling it out for control of a mythical space called KGF.

In actuality ‘KGF’ stands for Kolar Gold Fields, a sad town where they once mined gold, until the cost made extraction unviable. In ‘KGF: Chapter 2’, it is a secret industrial empire controlled by Rocky (Yash), who rules it.

The story does not bear recounting but it contains an excess of colourful personalities with names like Adheera (Rocky’s principal adversary), Vijayendra Ingalagi (whose father’s book ‘El Dorado’ chronicled the history of ‘KGF’), Shetty and Inayat Khalil who are rivals in the gold smuggling trade (India and Dubai), Kanneganti Raghavan, director of the CBI, Guru Pandian and Ramika Sen, successive Prime Ministers of India.

The film must be among the noisiest ever and digital effects produce the impressions of a vast and terrifying landscape in which forests and mines abound. An army of workers — numbering a million or more — willing to give their lives for Rocky also fill the frames.

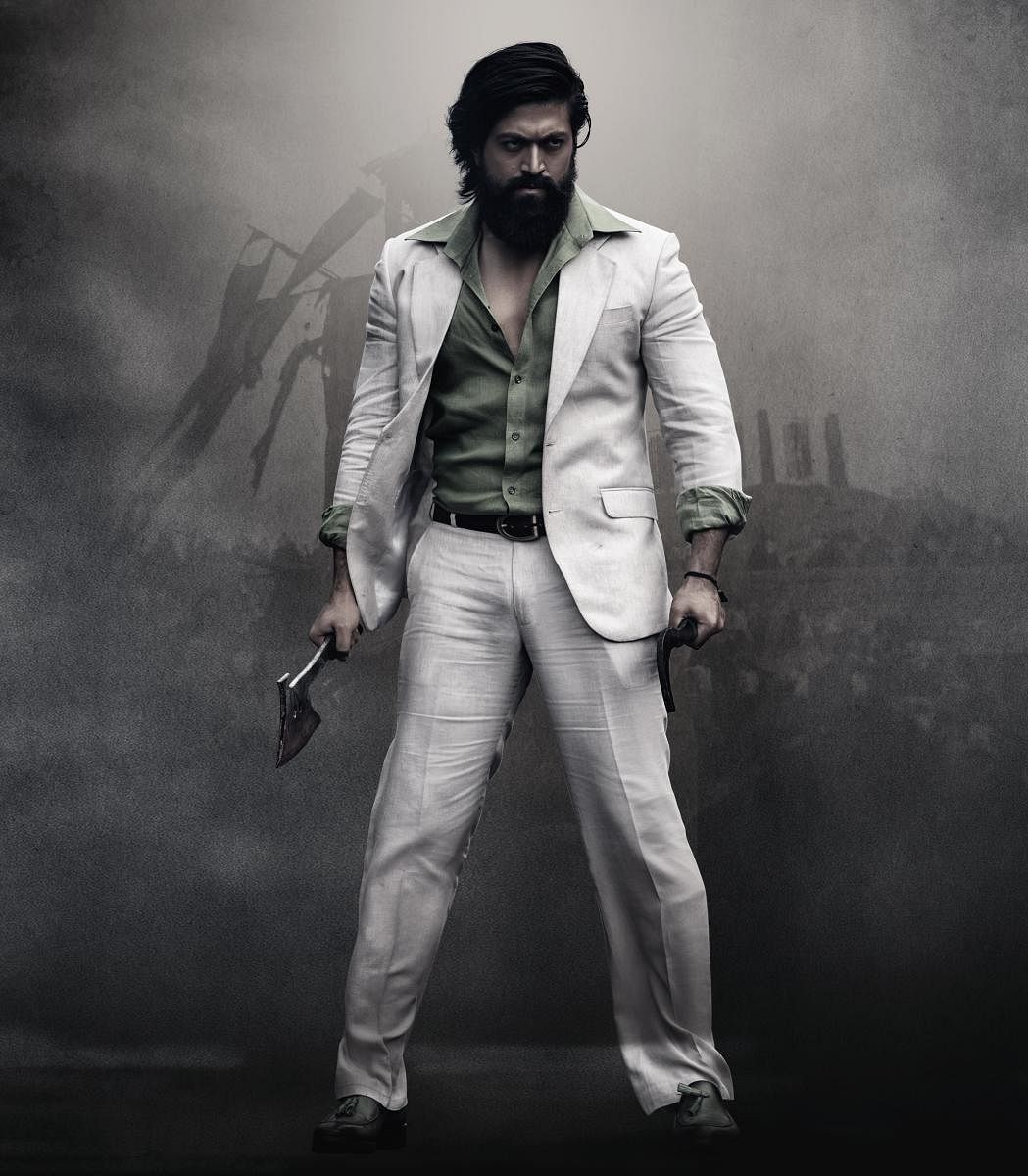

To give an idea of how the principal dramatis personae are conceived, those with unkempt facial hair are usually criminals who have made a place for themselves in the world. For instance, in the Telugu film ‘Pushpa’ (2021), the protagonist with unkempt facial hair is a criminal battling the forces of the state. In ‘Arjun Reddy/ Kabir Singh’ (2017) also, unkempt facial hair connoted resistance to authority. Here the protagonist has risen from the smallest beginnings. Only a mother is mentioned, but in ‘Pushpa’ he was the illegitimate son of a landowner. Important in both films is the criminal hero not owing to ancestry. Distinct from those with unkempt facial hair are those who are better-groomed, like privileged bureaucrats, politicians, or businessmen.

‘KGF: Chapter 1’ was made in 2018, and at the conclusion of that film, Ramika Sen was a ‘no-nonsense’ politician. Here she comes to power when the weak government run by Guru Pandian falls after a no-confidence motion, and the ‘no-nonsense’ Ramika Sen is now a ‘dictator’.

The 1980s are mentioned and Ramika Sen resembles Mrs Gandhi, but one is not persuaded that the film is unrelated to the present. The film sidesteps ideology and only self-interest is paramount, since all people trust in the value of gold.

Yash as Rocky speaks a crude local Kannada and it was the same in ‘Pushpa’, the hero speaking a rustic Telugu; Rocky, himself once being poor, is also protector of the marginalised just as Pushparaju protected the powerless who depended on him.

Important in both films is the idea of the local criminal as a hero, at war with the state and the entrenched criminals in collusion with officialdom. The criminal is not allowed to harm policemen but with the brutal/corrupt methods attributed to them, there is no doubt that the audience is with the lawbreaker against state authority. The policeman brutalising the local hero is a recurring motif in Kannada cinema too, as in Puneeth Rajkumar’s films, and the eulogised nation is conspicuously absent in both ‘KGF: Chapter 2’ and ‘Pushpa’.

South Indian stars and films have been making inroads into Bollywood territory but where Hindi cinema has turned patriotic south Indian blockbusters eulogise only the local. ‘RRR’ was perfunctorily anti-colonial but it had little faith in its British villains and the emphasis was on local heroes and their prowess.

I see the anti-state motifs in the south Indian films as the antithesis of the patriotism in ‘The Kashmir Files’ and ‘Uri: The Surgical Strike’ (2019). The former film is less about ethnic cleansing than Hindus targeted by pro-Pakistani Muslims for their patriotism.

But even as these films discover nationalism, the other thread is taking the opposite position and drawing big crowds across India. It would seem that the local is actually supplanting the national across the country. Nationalist rhetoric is no longer the dominant note being heard since successes like ‘KGF: Chapter 2’ and ‘Pushpa’ work against it.

It implies that patriotic rhetoric excites Indians less than it once did. Making the success of the new regional cinema across India doubly significant is the concurrent decline of Bollywood, till

recently the dominant pan-national cinema, carrying multiple narratives of the nation. One wonders if it is the one-dimensional narrative of patriotism that has weakened these other ‘Indian’ narratives and seen them supplanted by regional or local motifs.

(The author is a well-known film critic).