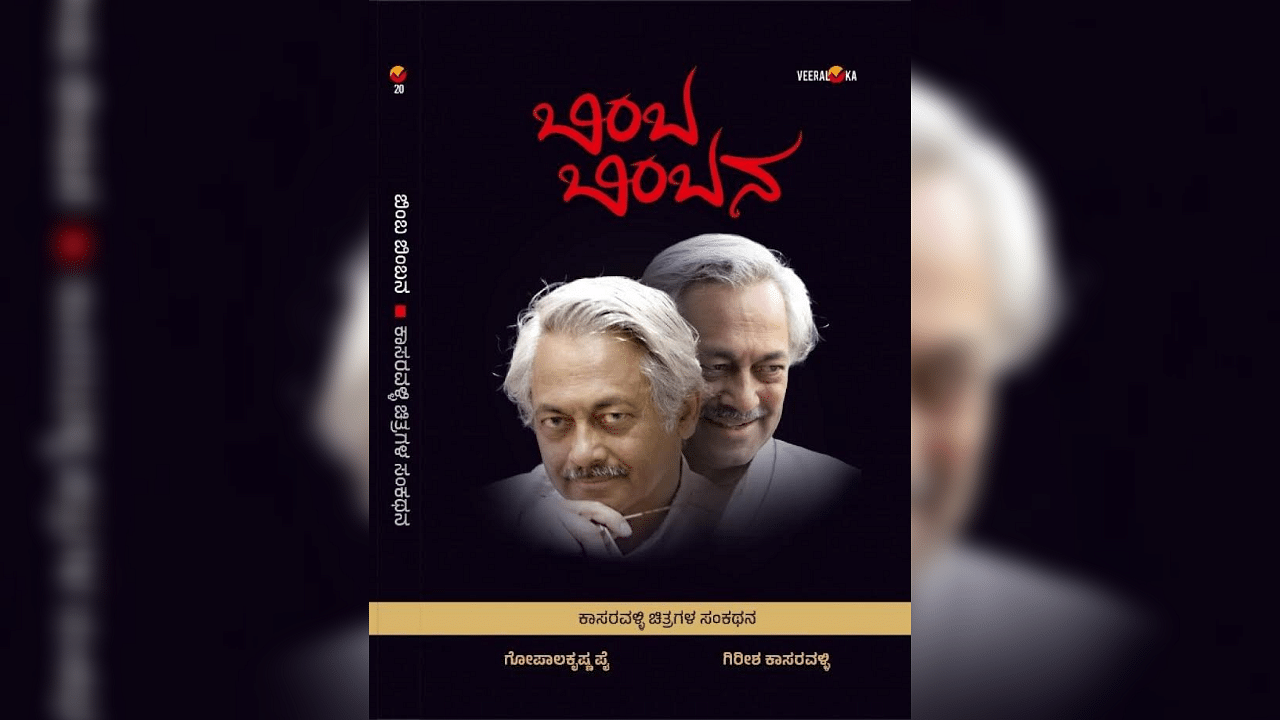

'Bimba Bimbana' cover

Credit: Special Arrangement

The just released Bimba Bimbana (Image Imaging) is a compilation of conversations between the celebrated Kannada filmmaker Girish Kasaravalli and Gopalakrishna Pai, Sahitya Academy award-winning author and National award-winning film script writer.

The book analyses all 14 feature films directed by Kasaravalli from his perspective, and dwells on how various elements of cinema converge to make a well constructed film. It serves as a reference source for aspiring filmmakers to understand elements of cinema and their convergence.

Kasaravalli belongs to a category of filmmakers not enthusiastic about mass culture; they believe in art as the true form of cinema. Exposed to world cinema before becoming a filmmaker, and trained at the prestigious Film and Television Institute of India, Kasaravalli’s knowledge of technique and technology decides his imaging processes.

The conversations with Pai, who has also written scripts and dialogues for Kasaravalli, emphasises the craft of filmmaking in the construction of images. However, his focus is on the politics of imaging in the real world and how it translates into visual narratives through the images he constructs.

It is evident from Kasaravalli’s repeated assertions that he is not a director out to satisfy the emotional needs of his audience, but one working to sensitise them to the physical world. The real world beckons him, but his preoccupation with imaging over image leads him to choose literary metaphors, the inspiration for which directly flows from literary texts. He uses the word ‘metaphor’ for almost every image he is conceiving. Most of his thoughts are indicative of the cultural ambience he grew up in and the literary works he was exposed to early in his career. Navya (modernist) literature was the dominant literary movement at that time. Metaphors and symbols for Navya writers were a creative need, as realist narratives were dominant in the earlier literary tradition they were trying to challenge.

Though this dichotomy does find some place in the conversations, it does not really play out as a creative challenge. This is in total contrast to the observations of the celebrated filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky, one of Kasaravalli’s favourites. In his autobiographical writings, the intellectual and philosophical filmmaker comes across as a pro-realist and anti-symbolist. Tarkovsky believed the most impactful way to portray a situation was with the reality of events rather than obtuse metaphors. Like Kasaravalli, he is also against the Russian Montage Theory (juxtaposing thesis, antithesis and synthesis) but believes that to be true to the essence of cinema is to leave everything formally within the frame and attempt to capture time in the film image the way that it exists in real life. This makes ‘rhythm’, and not editing, the main formative element of cinema. Interestingly, Kasaravalli opposes montage for the cathartic impact it has on the audience, but a majority of realist filmmakers oppose it on the grounds of the ethics of constructing an image from concrete reality.

There have been publications in the nature of conversations with filmmakers; some biographies and autobiographies also use this method. But almost all focus on the persona of the artists and the cultural and socio-political contexts they work within. Rarely does one see a book like ‘Bimba Bimbana’, which exclusively documents the perspectives of a filmmaker on his own films. It is extraordinary in that sense, but it may also be fraught with limitations, making the filmmaking process more prosaic, and, to use philosophical jargon, more utilitarian. The lyrical qualities of any work of art grows with viewers and discerning critics responding to it. If the filmmaker explains it all, it may hinder the rich and abstract experiences that cinema may provoke beyond the imagination of the filmmaker.

The conversations in Bimba Bimbana rarely offer a glimpse of the personality of the filmmaker, unlike My Last Breath, autobiographical work of Luis Bunuel, master surrealist filmmaker. That is an informal, discursive and conversational account with his French script writer Carriere. It is clear that 'Bimba Bimbana' is targeted towards film students and helps academic film appreciation. While most such conversations throw light on the worldview and evolution of the filmmaker, this is more focused on the construction processes and decoding methodologies through already existing film theory ideas and texts.

A close comparison one can recall is the American film critic Godfrey Cheshire with the renowned Iranian film director Abbas Kiarostami, published in 2019. If conversations in Bimba Bimbana are prompted and disciplined, Cheshire’s conversation with Kiarostami brings to the fore a medium which mostly refuses to be in order. Though the conversations in that book touch upon various topics, one anecdote beats them all.

Talking about his film Close Up, Kiarostami says he was at a festival in Germany when the projectionist mixed up the reels. Kiarostami was about to go up to the projection booth and straighten him out when he realised he liked the film better in the wrongly projected order. And so he went back and re-edited the film in the way that it had been shown incorrectly in Germany. Cheshire then quotes what Jean Luc Goddard had said. During his revolutionary period in the late 60s, there were a couple of films where Godard thought the projectionist should flip a coin to decide which order to show the reels in. He also said if a film was good, it didn’t matter what order the reels were shown in.

Cinema, a scientific innovation with continuous technological upgrades, has remained an artistic tool for independent creative expression from its early stages. Its aesthetic discourses are as rich as those in other art forms. The discourses in Bimba Bimbana look at cinema as a holistic work. They emphasise the convergence of elements like cinematography, editing, sound, music, colour, and choice of actors rather than a confluence of creative ideas. This is essentially an approach characteristic of philosophy of science rather than aesthetics of art.

In the domain of art, the sum of the total is not always the whole as it happens in critiques of scientific reasoning. The idea of visual philosophy through its elements is a flawed one, as in any art, the connoisseur is looking for philosophy of life and not the work per se. Another significant absence is the Kannada cinema context in which Kasaravalli tried to create an alternative form. The communication techniques he rejected from traditional mainstream cinema and his notions of alternative communication needed more clarity. Though there are a few references to Indian texts like the Natyashastra, his oeuvre is dominated by Western theories of cinema.

The book helps new filmmakers understand art film construction as it has been received as an invention of the West, mostly Europe, but they have to look elsewhere for their creative sources.

('Bimba Bimbana', Veeraloka Prakashana, Rs 350)