The controversy over music composer Hamsalekha’s speech at an awards ceremony in Mysuru is taking curious turns. The latest is that he faces a police case for offending Brahmin sentiments. Camps supporting him and opposing him are fighting it out on social media.

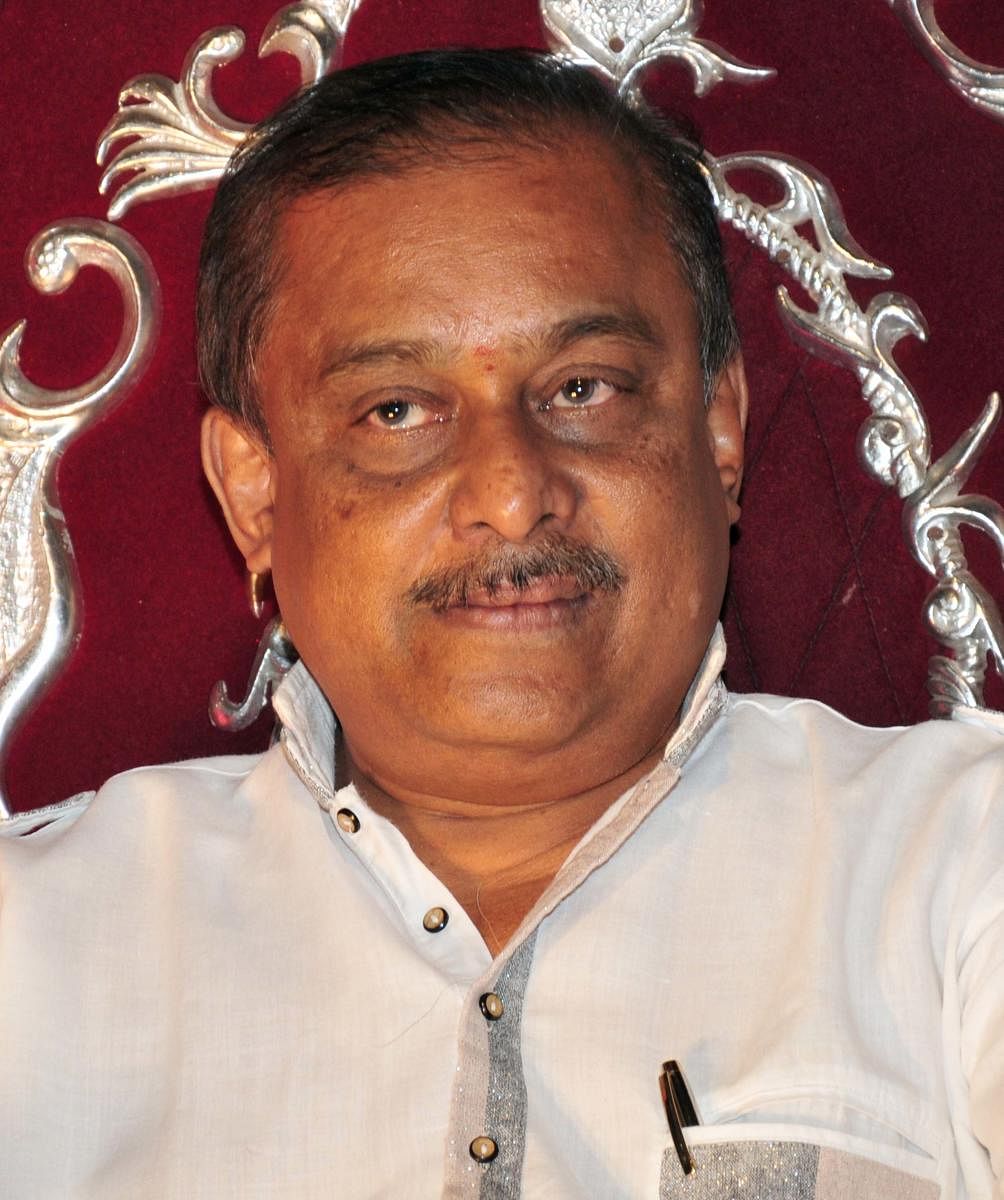

The lyricist-composer has produced hundreds of hit songs since the ‘90s. In fact, his debut ‘Premaloka’ is one of the country’s top musical hits, selling a record 35 lakh cassettes. With a background in theatre and an MA in Kannada literature, he is widely read and well informed. His songs are full of sentiment, humour and occasional naughtiness. He is a pioneer when it comes to using wit and street language in songs.

Hamsalekha’s observations about inclusivity and food habits have triggered this controversy. What he said: “I read a statement that the pontiff of the Pejawar mutt had visited and sat for a while at a Dalit’s house. He can sit there, but would he be able to eat if he were served chicken?” He followed this up with references to liver and sheep blood. “He can’t,” he remarked, suggesting that some gestures did not go beyond tokenism.

He went on to talk about how politicians were equally guilty of tokenism: “What is the big deal in privileged people going to Dalit homes? This has become a habit. Politicians do this. Kumaraswamy started this ‘grama vastavya’ (village stay). Ashok did it, Ashwathnarayan did it…”

Hamsalekha’s point was that these acts should go beyond mere display, and result in social integration. If they cared so much, he said, they should take the Dalits back with them and serve them at their homes.

He was making valid points, and putting this thoughts in the context of Dalit activism and the inspiration it should draw from Ambedkar and the Constitution. But at one point, he started playing to the gallery and talking about food.

This is a private space, an area of personal preference, and mocking those who eat vegetarian is as unacceptable as mocking those who eat meat. Hamsalekha should have exercised restraint, knowing full well that he was speaking on a stage, and his speech would be recorded and reported

widely. It is just not right to humiliate someone for what they eat, and he was citing the example of an orthodox swamiji who is no longer around to defend himself.

Within hours of TV channels going all out with footage of his speech, Hamsalekha realised he had crossed a line. Many channels edited out the context in which he had said what he said, and he was painted as a mischief monger. He soon released a video apology, saying he should have realised not everything should be said on stage. “I seek forgiveness... Even my wife did not like what I said,” he said.

It is a sign of the times that his speech sparked no debate about the central topic of inclusiveness and the perils of tokenism. It all ended in abuse and wild mud-slinging. The camp opposing him went into a frenzy quoting his naughtier songs and painting him as a lascivious character. Those supporting him ran campaigns with hashtags such as #BaadeNamGaadu (Meat is our God). Rabble rousers in politics have now jumped into the fray, and another distraction is playing out.

(The author is a well-known film maker, now working on a multimedia project on Gandhi.)