In the year he would have turned 83, John Abraham remains vastly underrated, and yet the idol of a cult that swears by him. John’s equation with fame today is pretty much what it was during the time of his death 34 years ago: He was held dearly by a group of artistes and intellectuals who believed he was a genius, but when he fell from the top floor of a building and was taken to the Calicut Medical College, no one recognised him. He died anonymous.

For his birthday this year, which falls on August 11, ‘Potato Eaters’, a cultural front devoted to people-centric art, has uploaded a 1080p resolution copy of his last, least conventional and most famous film, ‘Amma Ariyan’. Nachi Guspathiya, the founding member of the collective, also uploaded a Zoom call video that he had with ‘Amma Ariyan’s’ cinematographer Venu and editor Bina Paul.

‘Potato Eaters’ is shaped by John’s sensibility of cinema for the masses, and inspired in part by John’s own collective, Odessa. The name is a homage to Vincent Van Gogh’s painting of the same name and its logo is a joke on the Bible’s ‘Book of Genesis’, with Adam and Eve sharing a potato instead of the fruit of knowledge usually depicted as an apple.

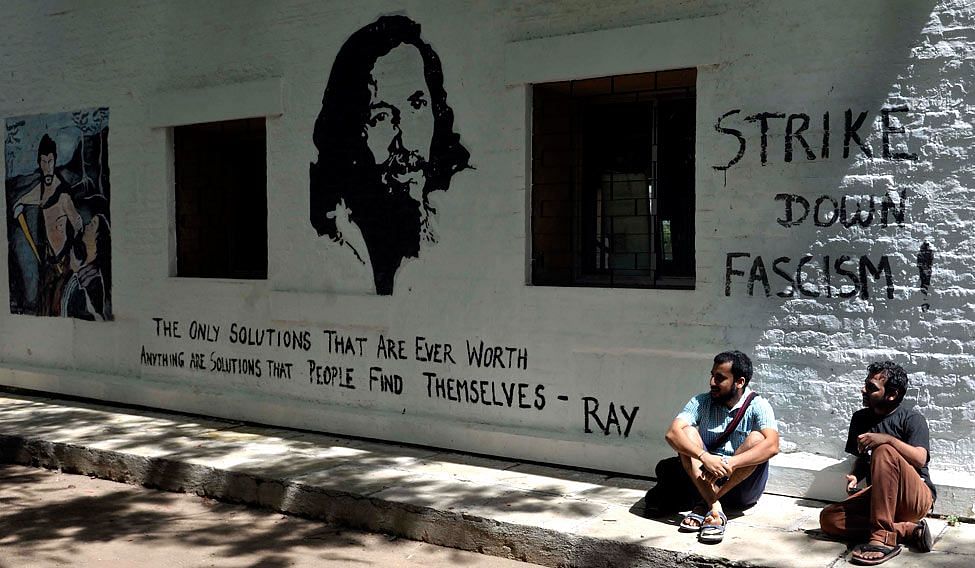

Uploading a copy of a John Abraham film on YouTube is not just not illegal but is also in the spirit of Odessa, which did not look at cinema as a money-making enterprise. But the fact that ‘Amma Ariyan’ was chosen over his other films has to do with how the film connects to our time. The film is an expose of state-sponsored cruelty and of a police force that need not answer to anyone. The symbols the film uses – Marxist poetry attacking apolitical intellectuals, Che Guevara, Mao Tse-Tung – may have been on the fringe when the film released in 1986, but are considered outright dangerous now. What may be most prescient is that at the centre of the story is a tabla player whose hands were crushed in police torture. The film, in which disillusionment with the establishment is a constant thematic undercurrent, begins with the man’s suicide.

“Even two people who were part of the ‘Amma Ariyan’ crew killed themselves a little after the movie was made,” Venu says.

Odessa found the funds for ‘Amma Ariyan’ by collecting small amounts of money from households across Kerala. Each contributor became a stakeholder in the film. The film was never released commercially; instead, Odessa took the film back to its “producers” and screened it for them with a projector free of cost. Hundreds of these people also came to act in the film, whether as a group doing karate on the beach, workers in a protest march or to simply stand in a queue for rice as John trolleyed Venu and the camera around for a shot unusually long for its time. These people, who appear only for a few seconds, maybe considered extras in a mainstream film, but in a film designed to not have a fixed centre, it is hard to state that some people are more important than others.

As Venu and Bina get talking, they reveal John as a disruptive genius, an extremely well-read person who never managed to hold on to a book; a filmmaker who had to stop his constant drinking to bring some discipline to his production, but whose drunken shots often looked better.

John took his story from ordinary people’s protests. There was plot, in a weak sense of the word; the film may have been held together by the death of tabla player, but the crux was the camera that travelled the length of Kerala covering oppression and resistance.

Often, incidents shown in the film had happened in the areas they were shooting. “The people in a scene may have been the people there during the protest,” Venu says. “When we went to Calicut Medical College, there was a historical strike going on there. And while what we shot was not the actual protest, John was able to capture the energy of the live situation,” Bina says.

“It was not like he imagined these sequences. It’s very interesting because when we consider what documentary is and what fiction is in this situation, this film becomes our memory of that event, which is not true. But John worked at a level where he was able to combine both. For him, this was the reporting of a period.”

Bina says that once they were travelling in a jeep when John decided to get out and start climbing a nearby hill, and that is how the early scene on the hill, with Pablo Neruda’s ‘Nothing but death’ recited in the background came to be. “Sometimes we don’t even know what we are going to shoot. This is not because John did not want to tell me, it’s because he himself did not know,” Venu says.

While Bina and Venu seemed skeptical during the call whether a film like ‘Amma Ariyan’ can be made today, Nachi later said in a call with me that John does not have an equivalent in Indian cinema today. Not that he has not had superficial imitators, who grow a beard, get drunk and claim the legacy of John – “Clone Abrahams”, Venu dubs them. It is also not that the times have changed -- in 2020, there are smartphones that can shoot better in natural light than what ‘Amma Ariyan’ did with controlled lighting, but the lack of novelty in standing in front of a camera may not draw a crowd the way John did. The reason we cannot make such a film may simply be what Venu thinks it is: “Who wants to make a film like that now?”