The barbershop tradition in American popular music is said to have originated in haircut salons where Black men could hang out informally without attracting adverse attention.

The Bangalore establishments I remember from the 1970s and the 1980s were halls of repeating mirrors usually run by Telugu-speaking men who would ask terse questions such as scissor-a? machine-aa? If you were lucky enough to find an empty throne to usurp before other comers.

More often than not, you would have to wait a small eternity because there would be three men at work and five others who had got there before.

There was nothing to do but observe the details of the spectacle before you: the snip-snipping of scissors, the snatches of conversation, the periodic thumps of towels, the fascinating khat-khatte of the man’s knuckles as he massaged some brave fellow’s head before pulling his ears and finally that terrifying twist of the skull to left and right, the smells of hair oil, shaving soap, scented water sprayed at the scalp of the waiting victim, and the talcum powder dustings that hung like clouds of glory upon the victorious finisher as he surveyed the morning’s work and grunted approval.

Inevitably, every salon had dozens of film magazines, the day’s Kannada newspaper, and as if by unspoken agreement, a copy of Screen, the film business periodical. Every copy of Screen I have ever read was in the confines of a barber’s.

I shouldn’t forget the most important detail. These many morning hours of my boyhood never clotted or congealed about my tender ears perhaps because there was always a radio on in every saloon, and that radio was always tuned to Akashvani Bangalore, or to Vividh Bharati. These were probably my first actual introductions to Kannada film music, to sugama sangeetha, and to the news in Kannada, depending on the hour. The initial moment of irritation at finding no empty chair would quickly evaporate, and I would be carried away into a soundscape that gradually blotted out all that flying hair, and eventually the terrors of the chair including the ticklish machine finish, and the knife that came out to smooth your shriven neck.

This bending of time, this holdain to the grinding gears of the universe is something that began thus for me with Kannada film music. I began tuning in all by myself at home, soon enough, to programmes called Nandana, Inchara, and Brindavana because I craved that simple airborne ski-er feeling that understanding a phrase like hani hani aagi bandittu (it came in little drops) could bring.

It was in this season of freely granted rapture that I came across the name of K S Nissar Ahmed for the first time.

The announcer would reel off the names of singers, music director, lyricist, and film before playing each number, and I sat up when they announced his name because I had seen it in the papers and knew that he was a big deal and a poet.

I knew my way around the conventional moaning and sighing of ordinary Kannada filmi numbers, but these lines were different. They were about fascinated yearning, and offer up a kind of entreaty, and derive their emotional force from the fact that the mere presence of somebody you are drawn to can fill everything with freshness.

I had never come across words like these — where I could find a kind of outline easily but found myself defeated in parsing them fully because of their compression. That edge of the peripheries of vision feeling that these lines refer to is as much the experience of the listener chasing the words as it might be that of the lover who craves the presence of a beloved. This was a moment of discovery.

This capacity to take the familiar, and set it moving, till it becomes new again, is something that seems to have been part of Nissar Ahmad’s craft.

This is often a desire to avoid mystification for its own sake, and a companion urge to sniff out the remnants of the mysterious in the things we have forgotten because we think we know them well enough. The dialect of language-love and linguistic exceptionalism, for instance, is usually lugubrious and routinely produces bad, noisy poetry, terrible laundry lists and high-minded boredom. In his hands, the very genre is brought down to earth and rewritten.

The thaayi he addresses in his most well-known poem is born of definite interactions between history and place rather than through mystical conferment. His Nityotsava looks askance, perhaps, at language-love as occasion and observance and offers us an alternative spectacle; the paradox of language as a continuously festive impulse.

Nissar Ahmad’s commitments towards a public, accessible poetry may have been shaped by his beginnings as a youngster who read his poems out on the radio. Another such marvel of wry precision is his Raman Satta Suddhi which gives a tight bum-kick to the idea of poets musing in public about serious matters— I sense a rude gesture in the direction of poems such as Auden mourning Yeats even.

As the speaker grieves about CV Raman’s passing, he is interrupted by the shouts of the peasant Hanuma who is separated from his epic patron by the poet’s capacity for irony. He has just begun on a What’s he to Hanuma when the peasant’s words remind him of the worlds within worlds that we all experience without always comprehending, and having found his comeuppance, he falls silent.

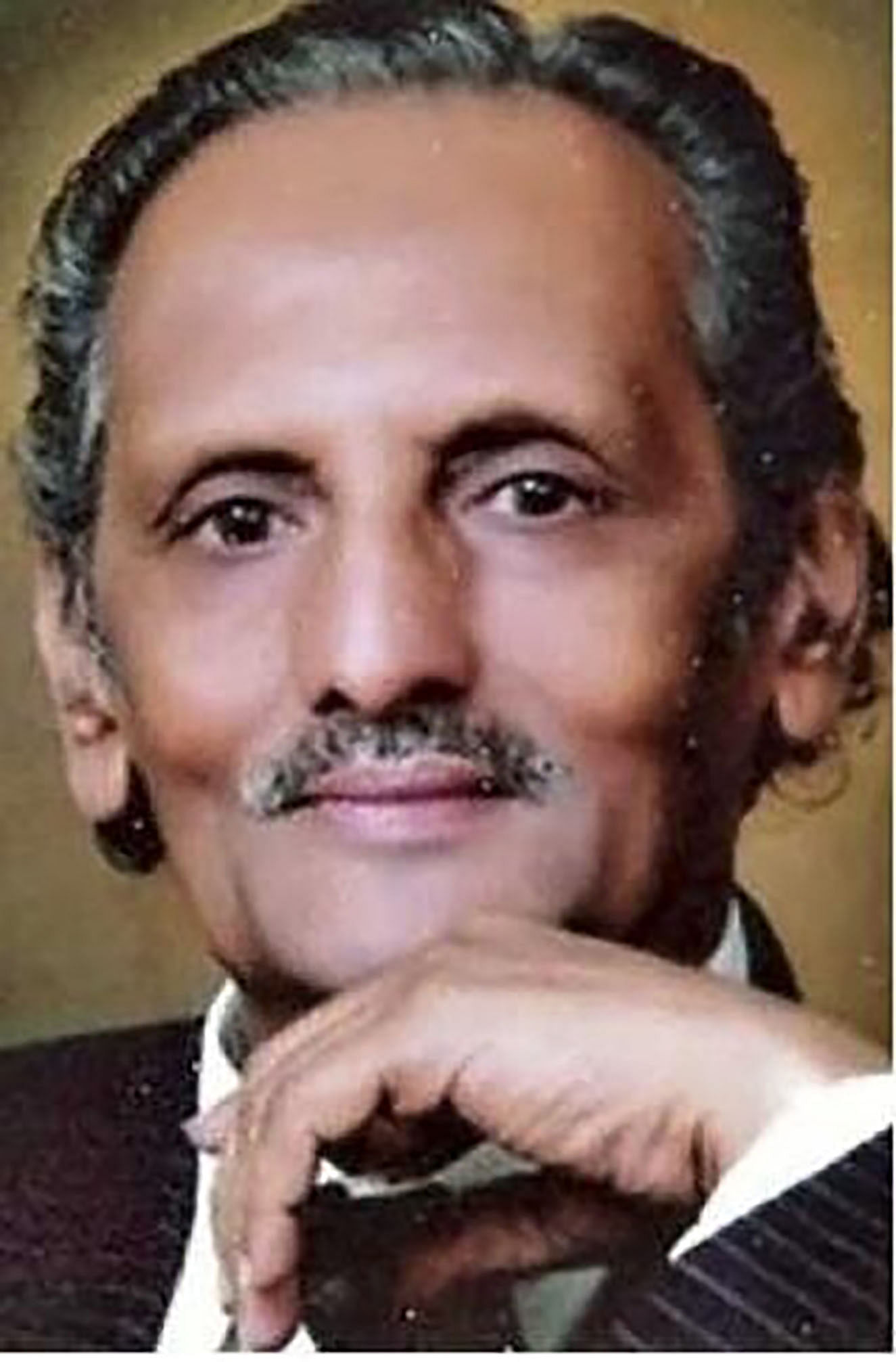

Here he was, an outsider of sorts, an Urdu-speaking Muslim, and Avarna in a stratified world, who chose to cross over into writing in Kannada, and to thus build a little bridge and be, on a human scale, what the word Tirthankara means in Jaina culture — a maker of crossings, an expander of our capacity to see others, a builder of the plurivocal public space that Karnataka is home to, an emphatic wearer of suits much like that man who wore a blue suit, a dignified answer to lawmakers who see no role for minorities in their brave new worlds except as puncture-wallahs.