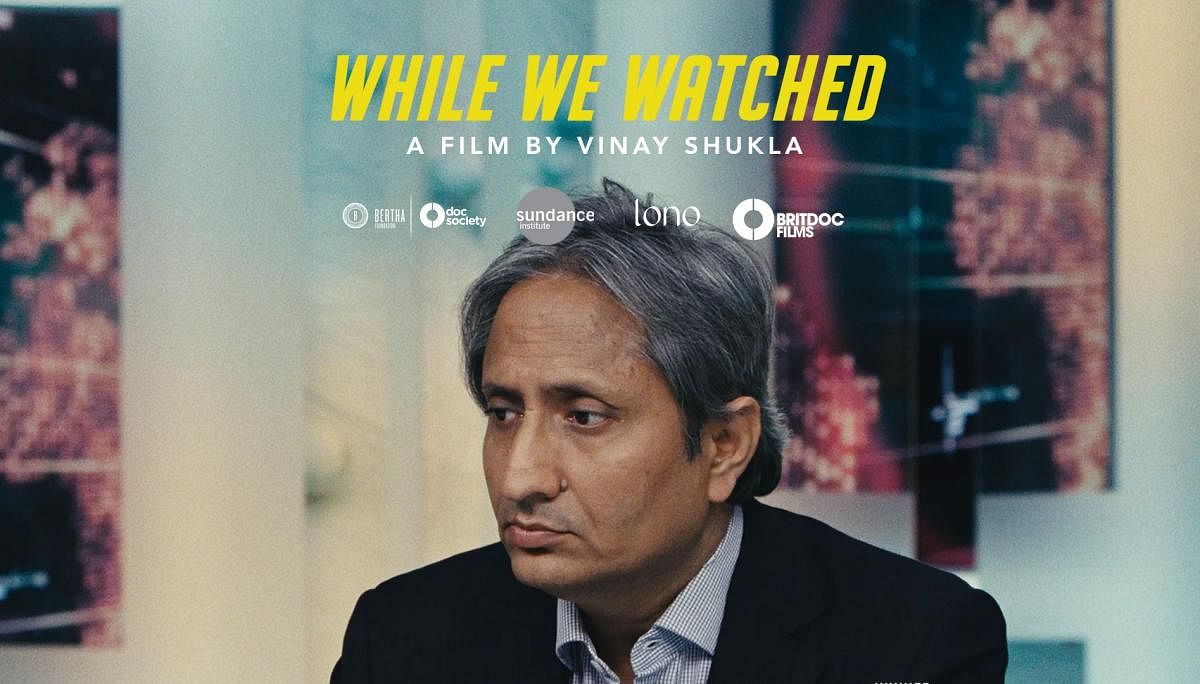

The much-anticipated documentary 'While We Watched' is a story that follows broadcast journalist Ravish Kumar, as he navigates the shifting sands of truth and disinformation in his profession. It is a glance into the abyss of factual reporting, which is on a steep decline worldwide. Director Vinay Shukla tells Showtime about the art of documenting India’s "lone voice" in televised news and his journey and craft of documentary-making. Excerpts:

How did you get into documentary filmmaking?

I assisted on a Bollywood film, which helped me understand quickly that it wasn't the space for me. I wanted to teach myself the craft of filmmaking, but I didn't come from a film background, so I borrowed DSLRs from friends and began recording. I invested in an audio recorder, and I started recording my family. It helped me understand how to shoot with people. Much later, I understood that that's where my understanding of placing the camera and how to shoot without affecting people came from.

How did 'An Insignificant Man' happen?

In 2012, when the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) was just starting out, and my co-director and I went to a rally in Delhi. We found this fascinating story there, but nobody was shooting it. We asked them if they'd be open to us documenting them, and they agreed. We didn't even have sound equipment on that film. We were using just our DSLRs. Slowly, as the party became bigger, our project got bigger.

How much experience did you have before you started documenting with the AAP?

We became filmmakers while making the film. I had made a short film before, but it wasn't anything significant. We had some understanding of the camera and the cinematic language, which came from watching lots of movies. But there is a big bridge between what you aspire to and what you can do. We traversed that bridge while working on that film.

Did you plan to produce 'An Insignificant Man' on a large scale?

We aspired to, but we were lucky it went far beyond anything we could have foreseen.

How did Anand Patwardhan inspire you?

My first interaction with Anand was when he visited my college. His films stayed with me for weeks after that. I would find myself thinking about the smaller segments of his films. It helped me understand the power of documentaries.

It was after following Anand's work that I decided to make my first film. My first short film just before 'An Insignificant Man' was a political film about the Emergency of 1975. I told Anand about it, and he wasn't impressed. I still made the film. But I go back to him once in a while, as he is somebody I look up to as a master of his craft. A lot of people talk about Anand for his activism and politics, but I was drawn towards the sheer poetry and the empathy he had for people. His films were a completely new language for me.

Is the political nature of your films on account of your general interest in politics?

My teenage consciousness was shaped in the early 2000s. The pop culture films that came out then in India and internationally were quite political. The narrative was that if you wanted to be part of the change, you could not shun politics, so all art should address politics. I still have some of that idealism, which is challenged very often, but I am trying to work on a fiction project.

Why Ravish Kumar?

Ravish is a guy who instead of telling the audience what they needed, chastised them. I identified that this was a tired protagonist, a journalist who in his own understanding had seen a better world. He wasn't a typical young idealist, but an old one. Most journalism films were feel-good and happy, wherein a scribe does one story that changes the world. They didn't reflect the mood we see in journalism in India. So, I decided to make a film that captures the trauma of watching Indian TV news nowadays.

Was the motive to capture the true essence of broadcast journalism?

There is a moral load that you take on to find the 'true essence'. I didn't go for that. I wanted to make a journalism film that would give people a different perspective on television news. As a documentary maker, every time I have gone into people's lives who are in the public eye, I have gained respect for them. Being in the public eye can wear people down. People who continue to be in these professions for their lives see a lot of wear and tear. What happens to them and their families, and how they still persist, is also what the film is about.

Did you shadow him just in the newsroom?

We were everywhere. We tried to tell the story of the times that we live in, and it's a deeply personal story.

How did you condense all the material into 90 minutes of footage?

Documentaries are essentially made on the edit desk. We shot for almost 8 to 10 hours a day for two years. Every day, when we finished shooting, we made bullet points about what happened on that particular day. We prepared a daily summary. After the shoot, we resolved the entire footage and made detailed notes, categorised all days by costumes, just like any big production would. Like say, Game of Thrones, wherein you catalogue people's costumes, accessories, etc. We catalogued every clip number, and a description would be put against every clip. Then we took a deep dive into the story and structure.

I had a young bunch who sat in a room for about a year and a half, just orchestrating ideas daily, trying to prepare the rough cut first, which was two hours long. Then we condensed it into 90 minutes to make a film that was emotionally and intellectually saying things that we wanted to say. I wanted it to be a profoundly personal story via Ravish about adult loneliness.

What level of patience does one need to become a documentary filmmaker?

Lots of introspection goes into documentary making. Whenever you're shooting, you don't know if this will amount to anything. You wonder every day if you missed a shot that you wanted in the film. The artistic insecurities and emotional vulnerabilities one carries take a bigger toll on you because of the project's duration.

Do documentary filmmakers ever meddle with the subjects?

No. The best part about documenting Ravish was that he was so focussed that he didn't care about us being around him. He can produce a show from a traffic signal.

What was the takeaway as a filmmaker from this documentary?

Over the last decade, journalists and journalism have been given a shoddy reputation. It's essential to understand the value of journalism and the value of the process. Journalists are often not trained to deal with the complexities of real life. My biggest learning from the process was to look at these aspects to strengthen the institution. While shooting the documentary, I realised that instead of us gazing at Ravish's personality and telling people who he actually is, we have to focus on the institution because that could make things better for us.