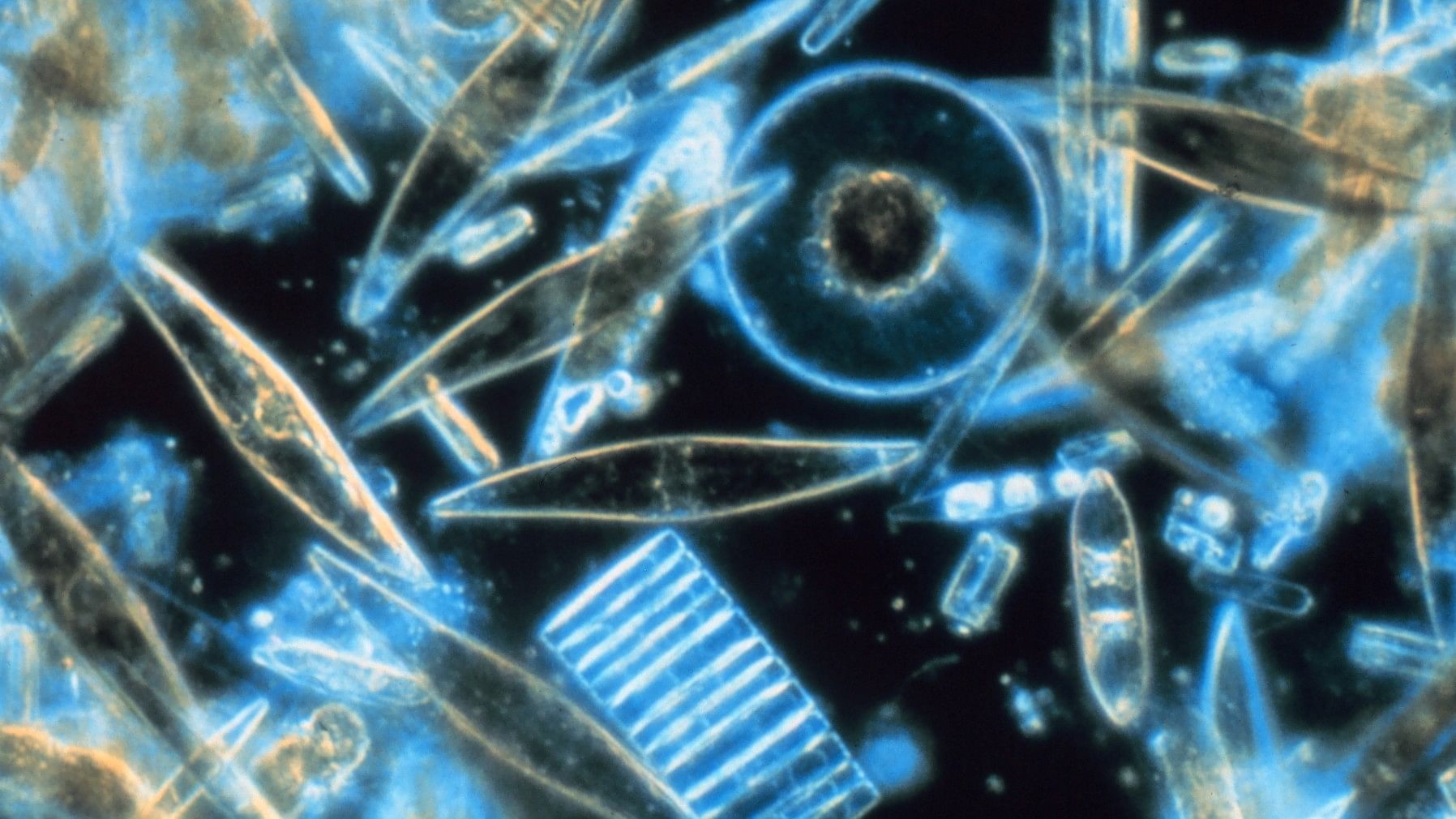

Diatoms as seen through microscope.

Courtesy: Karthick Balasubramanian

When diatomist Karthick Balasubramanian visited the Inter-University Accelerator Centre, a research institute in Delhi, he serendipitously met archaeologist C R Gayathri, who too was at the centre with a few ancient pottery shards. They were at the centre to look back in time—biological and archaeological—for their respective research and got talking. Over the next six years, ideas bounced off each other resulting in the first-of-its-kind scientific study that uses diatoms from ancient pottery in Asia to get a glimpse of the prehistoric climate that existed nearly 3500 years ago.

In a recent study, Balasubramanian and his colleague at Pune’s Agharkar Research Institute, along with Gayathri from the Archaeological Survey of India, report what the local environment looked like during the Iron Age in the lower Kaveri Basin by examining fossilised diatoms from pottery pieces. The Iron Age is a prehistoric period between 1500 BC and 600 BC when humans used iron and steel to make tools and weapons. The study was published in the journal Current Science.

Deriving archaeological insights

Diatoms are microscopic golden-brown algae abundant in freshwater and marine habitats. Although only about 70,000 species are known today, scientists estimate there might be around two million species on the planet. Not all diatoms are found everywhere. Water temperature, pH, electrical conductivity, and water current all affect what species of diatoms occur where. Species that occur in a hot spring are poles apart from those found in an ice core.

Thanks to their special cell walls, diatoms can be preserved for thousands of years. “Diatoms are the most successful organisms in getting fossilised because their cell wall is made up of silica—it’s like a piece of glass,” says Balasubramanian. “That’s why diatoms are one of the most commonly used paleoenvironmental tools.”

As the planet’s environment cyclically changes due to phenomena such as the El-Niño Southern Oscillations, which last a couple of years, or the Milankovitch cycles, which send the planet in and out of ice ages, different species of diatoms cycle through these periods in the same geographical region. Hence, by looking at what species are present at a given point in time, scientists can reasonably predict the water temperature, pH, water quality, and other environmental parameters of the time.

The current study relies on diatoms preserved in time in the sediments of freshwater lakes. Paul Hamilton, the curator of the algae collection at the Canadian Museum of Nature in Ottawa, Canada, likens the layers of sediments in a lake deposited year after year, along with the diatoms that existed during that time, to tree rings. “We can count back using these layers to pinpoint the exact date and really pinpoint exactly what the environment was like.” Hamilton has used diatoms from a Canadian lake to supplement archaeological knowledge about the Indigenous people who lived on the lake shore between 1200 and 1400 BC. He was not involved in the current study.

Insights into the Iron Age

Balasubramanian and his colleagues used 26 pottery pieces extracted from six Iron Age urn burial sites along the Kaveri River in Tamil Nadu: Nallur, Tiruvaymur, Avur-Saluvanpettai, Milalainattam, Tirubuvanam, and Tepperumalnallur. They ground these pieces with a motor pestle and observed the powder under a scanning electron microscope to find fossilised diatom valves—the silica cell walls with intricate patterns.

The study found fossilised remains of 41 different diatoms in pottery excavated at four of the six sites. Most of the individuals belonged to the genus Nitzschia, which is typically found in the sediments of lakes and rivers rich in nutrients or heavily polluted. This genus was found in all pottery pieces, indicating that the clay used to make them came from the sediments of a polluted local lake. The anthropogenic pollution indicates the presence of human settlements at the site in the past.

Diatoms from the genus Hantzschia were found only in pottery pieces excavated from Tepperumalnallur, while pottery shards from Avur-Saluvanpettai were the only ones that had diatoms from the genus Luticola. Since both these diatoms can tolerate drying up, the researchers posit the clay used to make the pots could have come from waterbodies with stagnant or slow-running water, where the sediments could remain dry for long periods of time.

A new tool in archaeology

So far, most archaeological studies give a glimpse of what people in early settlements used, the populations of such settlements, and the tool-making and pottery techniques they employed. “Archeology does not focus on what the early environment looked like,” says Balasubramanian. “It just gives a very anthropocentric view.” The study shows how insights from tiny, microscopic diatoms could provide a larger context of the environment, which can hugely influence human settlements of the past.

“Diatom analysis of pottery can help in understanding the source of clay used by potters,” says historian and archaeologist Nayanjot Lahiri from Ashoka University, who was not involved in the study. “This has been done in many parts of the world and it is excellent that this is now being done by Karthick and his colleagues.”

Lahiri suggests the researchers could follow up with fieldwork around the sites to understand the sources of water in the vicinity and the nature of clay. “This would allow the analysed samples to be seen as forming part of a lived environment,” she says, adding that a few samples must also be sent to radiocarbon dating to determine the exact date of the artefacts. “The dates and diatoms, when combined with other proxies, will provide insights into palaeoecological processes and changes around the sites.”

With the current study’s promising findings, Balasubramanian is excited about the prospects of using diatom analysis in Indian archaeology. He has now partnered with the Tamil Nadu State Department of Archeology to explore possible cultural exchanges between people in the Kaveri basin and others on the subcontinent and to use his expertise as a diatomist to explore the country's rich history. “All over India, everything is an archaeological site,” he says.