I have had many good thoughts during my regulation two rounds of Shivaji Park. I can vouch for the fact that creative juices flow like crazy when I’m out there,’ writes critic, translator and award-winning author Shanta Gokhale — an assertion that is validated by her latest work, Shivaji Park: Dadar 28: History, Places, People. Drawing upon multiple sources — historical narratives, novels, plays, blog posts, anecdotes and reminiscences — she traces the birth, cultural and architectural evolution of the Mumbai locality where she herself has resided for nearly 80 years.

Calling the 28-acres park, ‘the most democratic of all open spaces in the city’, she delves into its roots. They lie in the 12th century when a series of migrations into the region began. Mahikavati, as the island of Mahim was known then, was a part of the Kalyani Chalukyas’ kingdom. An invading army led by Pratap Bimb from Champaner conquered it. Finding only adivasis and fishing communities on the island, Bimb decided that it must be inhabited by high castes. Accordingly, 66 suitable families were sent from Champaner.

Marathi ethos

It is interesting that subsequent foreign occupiers, the Portuguese and the British, having no interest in Mahim, allowed it to remain ‘a district of swamps, coconut groves, paddy fields and vegetable gardens.’ Consequently, the early settlers could be said to have engendered the cultural DNA — and nativist politics — that has come to be associated with Dadar. While it’s true that Bal Thackeray lived there, Gokhale notes that the area also saw several waves of settlers that lent its Marathi ethos a more versatile character. She documents the rise of various cultural movements. For instance, when the first cotton mills came up, Dadar was part of the mill district.

The workforce comprised of erstwhile seafaring communities like the Kolis, Kunbis and Bhandaris as well as the castes known in the hinterland as untouchables. ‘The mill-workers gave birth to a vibrant culture of music and drama, acquiring a fearless political voice, which writers like Annabhau Sathe, Shankarrao Kharat and Narayan Surve used forcefully in their poetry and fiction.’

Park after plague

The acreage known as Shivaji Park owes its existence to the plague years, 1896-1914. Congestion and unsanitary conditions were believed then to have caused the epidemic.

The solution lay in reclaiming land and creating new precincts that would open up to ‘healthful sea breezes’. Dadar, the first of Mumbai’s planned neighbourhoods, became famous for its Art Deco bungalows. The plots were marked around a grassy meadow that was converted into a park.

Named in 1927, the tercentenary year of Shivaji’s birth, it has an equestrian statue of the Maratha warrior king that comes with its own little story.

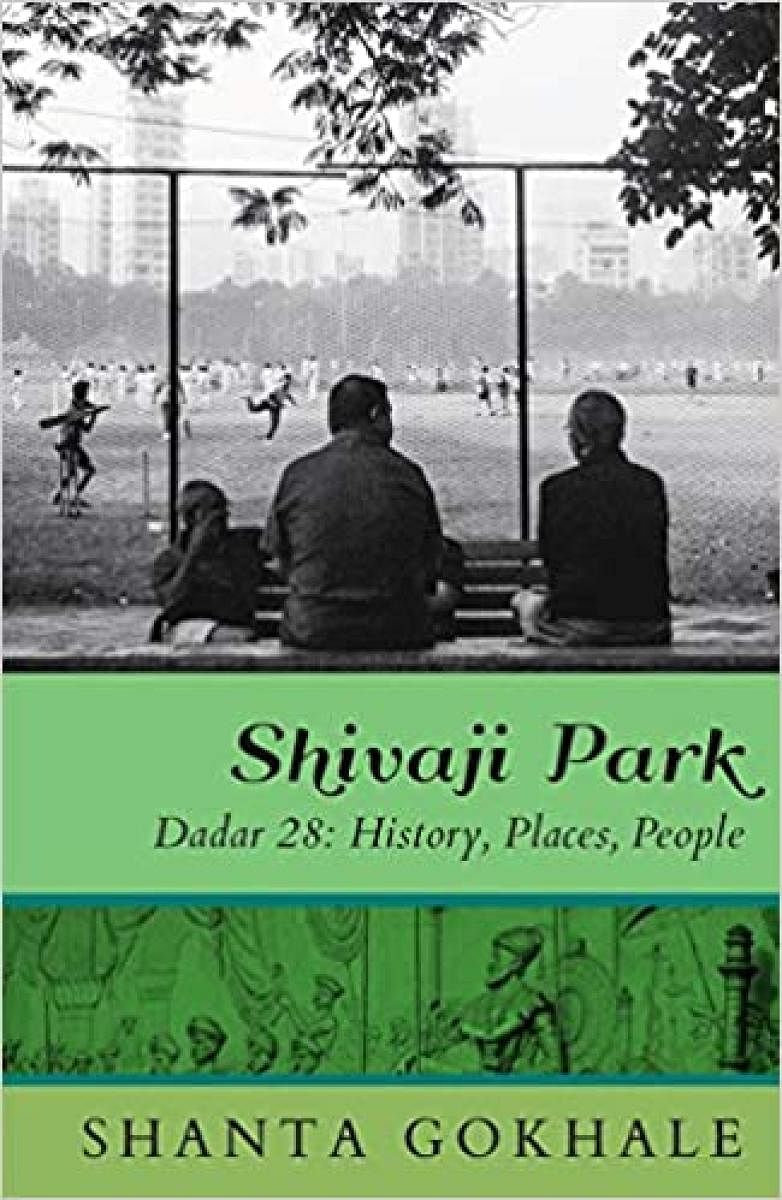

While the public space, designated as a playground, is associated famously with sports such as mallakhamb and cricket, it has also been used as a cultural space for just about everything — from the public cremation of Bal Thackeray to the annual Jagannath Yatra.

Reinforcing her point about egalitarianism, Gokhale describes the respectable middle-class families of her own building, Lalit Estate, and juxtaposes the passage with an observation about a short story that Manto wrote using Shivaji Park as a setting. She adds: ‘Our purpose is to point cracks that apparently existed in the middle-class front of the precinct’.

Candid and informative all the way, it is only in the last chapter, ‘Morning Walk’, that Gokhale turns lyrical, describing the park’s trees — copper pod, wild almond, banyan, bakul — and its walkers, including the 82-year-old stalker who too, she says, is a regular. As engaging as a walk in the park is this book.