Donna Williams, an Australian author, says, "Right from the start, from the time someone came up with the word ‘autism’, the condition has been judged from the outside, by its appearances, and not from the inside, according to how it is experienced." She should know, for she was diagnosed with autism. I believe what she says is true of most disabilities, not just autism. We've described disability to fit our ideas, often with a healthy dose of fantasy and a thick layer of pity.

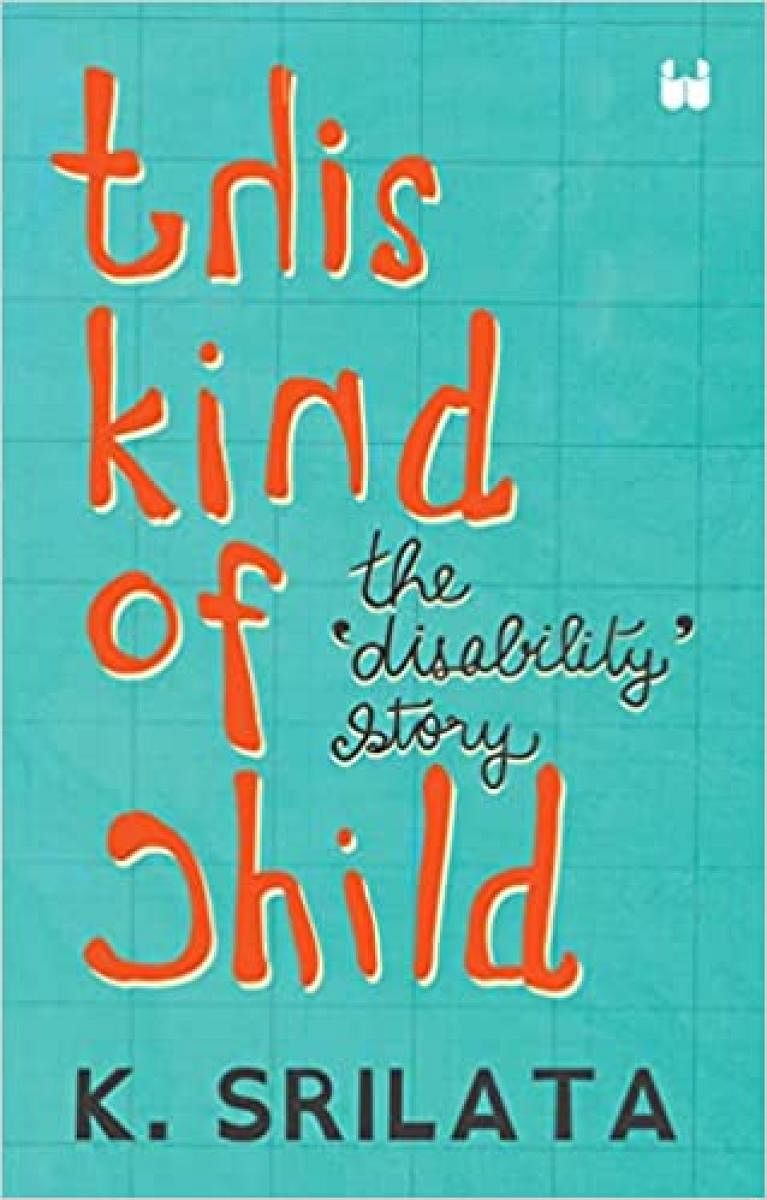

What the book This Kind of Child: The 'Disability' Story by K Srilata, does is cut through these filters and open our minds to inclusion, self-advocacy, and a rights-based approach to disability — in fact, to life in general. If these are just words to you, read the book. They begin to make sense and even prod you to accept them as the natural order of things.

The book mellows a few prejudices and sets new boundaries. How else could I wrap my head around the lives of Meagan and Mark, both legally blind, their pregnancy, and their parenting? Or Kirstein's first steps into motherhood in a world that is blind to her?

The book left me with so many heroes that it was difficult to choose stories to write about and lead this review with. I’d imagine I share the predicament of the author as she sat down to compile the book.

But that is not the point of the book. It is not an attempt to make heroes — the book documents the extraordinary efforts of some to achieve the joys of the ordinariness of life.

Like taking your two-and-a-half-year-old toddler to a Montessori school down the road; walking in the park and playing with others, or being able to hail a taxi to take your child to a clinic for vaccination. Just routine things that we do in life without thinking. These are not the things that need special talents. Yet, for many, it is a struggle.

Ask Zach, a kind, funny autistic 17-year-old. He will tell you that he likes his days planned to a "T." In fact, he thrives on structure. Digressing even slightly from the anticipated structure of the day can cause a meltdown for him. "It can result in emotional upheavals and an inability to reclaim a joy-filled day." Like a change of route because a sinkhole suddenly appears on the regular road. But these are barriers that are innate to the impairment.

There are others, some visible and many that are not. As Srilata notes, buildings without ramps are a barrier for the physically impaired, like traffic lights are for a person with a visual impairment. These are easier to navigate. What of others, like pedagogical practices and mechanisms for evaluation and assessment — systemic barriers that are seemingly impossible to surmount, even with legislation like the Right to Education? What about our attitudinal and socio-cultural barriers?

We disable the world to many of our own. The preamble to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities recognises that disability results from "interactions between persons with impairments and attitudinal and environmental barriers that hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others." All the able-bodied people, read that again. What is disabling is the way society structures and operates itself: the stereotypes, prejudices, dogmas, and notions of normal.

A visual storyteller, Dhaatri Venugunad wonders in the book why people expect sameness and homogeneity when heterogeneity is the natural order. Why can’t there be space for people who are different or for people who do things differently? The answers are not easy to come by. It needs deep introspection at multiple levels: individual, community, governmental, and societal.

This book engages diverse people at different levels — people with impairments, their friends, parents, caregivers, and community helpers like educators — to present multiple perspectives. It is divided into seven mini-books that flow seamlessly to present a cohesive picture of the disability community in India and abroad.

As with anything atypical, dyslexia is also a much-misunderstood disability. Specific learning disabilities, of which dyslexia is a subset, extend beyond mispronouncing "pqdb" or being unable to write quickly enough. It is also about being different, perceiving things differently, and reacting differently to situations than others.

Every person is unique, and her or his impairments are different. A dyslexic's condition is different from that of a visually or hearing impaired person, or, in fact, from another dyslexic's.

But the disablers seem to have a common thread: a system that is sympathetic but lacks empathy; that makes noises about supporting individual differences but makes "success" a straight jacket; that claims to take people along but leaves some standing by themselves at the periphery of the mainstream.

The stories — 37 in total, including interviews and personal accounts — sit on you like a thick layer of fog that refuses to lift until you alter your perceptions of what is normal.