Recently, at the age of 42, I finally learned to drive and got my license. I was among the older students in the classes I took, five of us at a time stuffed into a dark blue Maruti 800, taking turns to learn how to upshift and downshift gears on small, curving panchayat roads in central Kerala.

In one of the classes, our instructor had to meet someone at a hardware store so he made us drive onto the highway, far from our usual route. You could feel the atmosphere change in the car when he said we had to get on the highway: a silent chill settled in and there was heightened anxiety among the students. On the highway. With speeding cars and buses and trucks. While we were still barely capable of putting the car into third gear as we drove. After the class, I remember thinking that in all the books I’d read the only writer I had come across who captured that special mindset needed to drive on a high-speed road was Joan Didion.

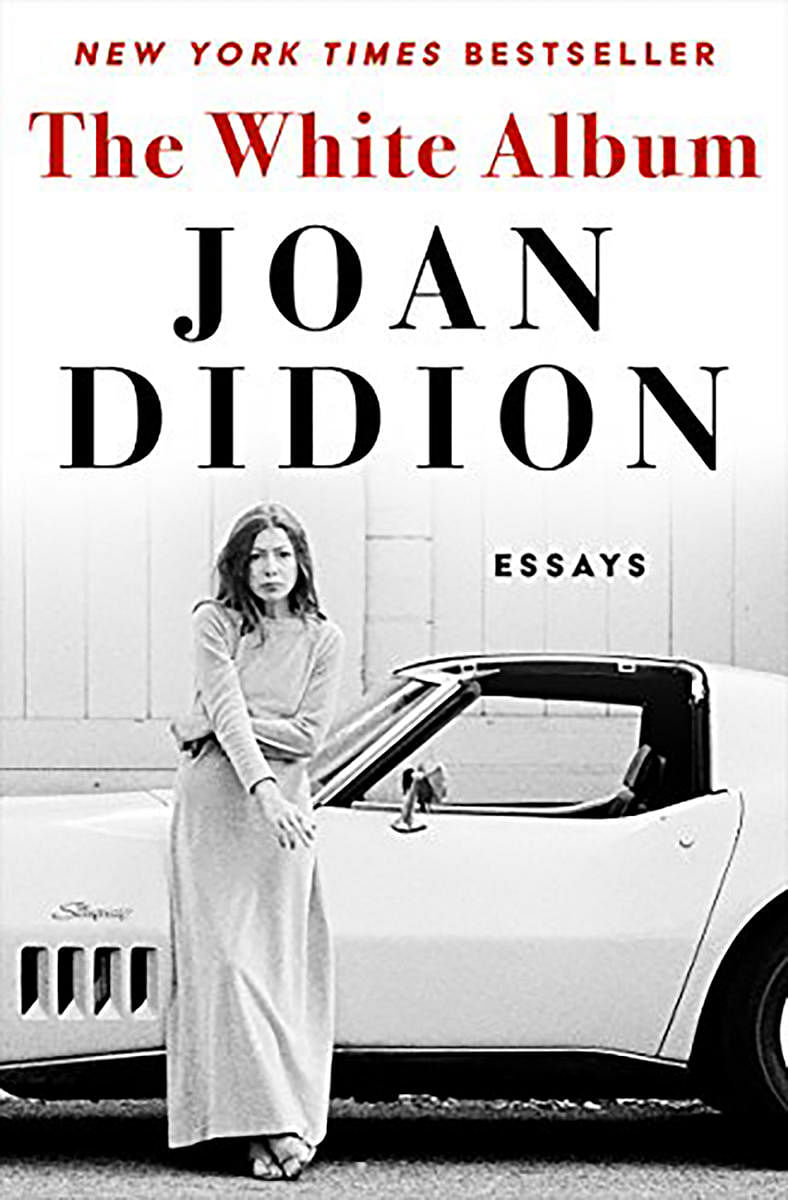

In the essay ‘Bureaucrats’ that appears in Didion’s seminal work of non-fiction, The White Album, she describes how, in the 1970s, the city of Los Angeles was trying to improve upon its transportation design and operations through a project called The Diamond Lane. Along with the details of bureaucratic processes and technological interventions that seemed to worsen the transportation woes of the city, Didion describes the act of driving on the freeway:

“Actual participation requires a total surrender, a concentration so intense as to seem a kind of narcosis, a rapture-of-the-freeway. The mind goes clean. The rhythm takes over.”

Didion’s reputation as a colossus in modern American literature was pretty much carved in stone by the time she passed away in 2021. The White Album, first published in 1979, includes so many of the pieces that earned her that reputation. The first essay in the collection, the one that lends its title to the book, has been one of those oft-quoted examples of non-fiction writing that makes even someone who hasn’t read it think they have. When the news of her death spread, The White Album’s first line — “We tell ourselves stories in order to live” — was what fans quoted on their social media accounts to mourn her, pausing in their collective grief to write that line and have it ping from one account to the next unto infinity.

But to have that one essay define the whole collection would be a mistake. While it best captures Didion’s sense of doom and anxiety as the world convulsed in a plethora of social and cultural movements in the 1960s and 70s, there is a lot of joy and pleasure to be gained in reading some of the lesser-known pieces in the book, like the ones on the Hoover Dam, California’s perpetual water crises, and the shopping mall. How strange to read that last one, titled On the Mall, and learn that Didion once harboured ambitions to be a shopping centre magnate, to subsidise her writing life.

In reading Didion’s prose, it’s impossible not to fall under the spell of her peculiar magic. So seductive is that voice in these pieces that you almost forget what she’s been trying to say about the unpredictability and messiness of modern life. You almost forget the worry and stress that animated Didion’s writerly voice and soul until the final line in a piece on Malibu that brings you back to earth with a thud. And there, in that hard landing that sneaks up on you after you’ve been drifting pleasantly along, is where Didion’s power lies.

The author is a writer and communications professional. When she’s not reading, writing or watching cat videos, she can be found on Instagram @saudha_k where she posts about reading, writing, and cats.

That One Book is a fortnightly column that does exactly what it says — it takes up one great classic and tells you why it is (still) great.