In the current national pastime of sacrificing the leaders of the national movement at the altar of self-serving present-day political rhetoric, it is easy to forget what India was like at the time of independence.

We have not just forgotten the larger challenges of poverty and hunger that the immediate post-independence leadership faced, but also the stories of the time that made present-day institutions. In what was princely Mysore, independence meant a maharaja having to come to terms with a democratic society, the elites of the princely state having to come to terms with the original new India, and the building of new institutions to deal with an uncertain future. It would be too much to expect a grandson’s memories of his grandparents to fill this void. But in the desert of manufactured history, every little bit of authenticity counts, especially when the grandfather in question set up a media institution that not only chronicled the changes in post-independence India, but was also, on occasion, a part of those changes.

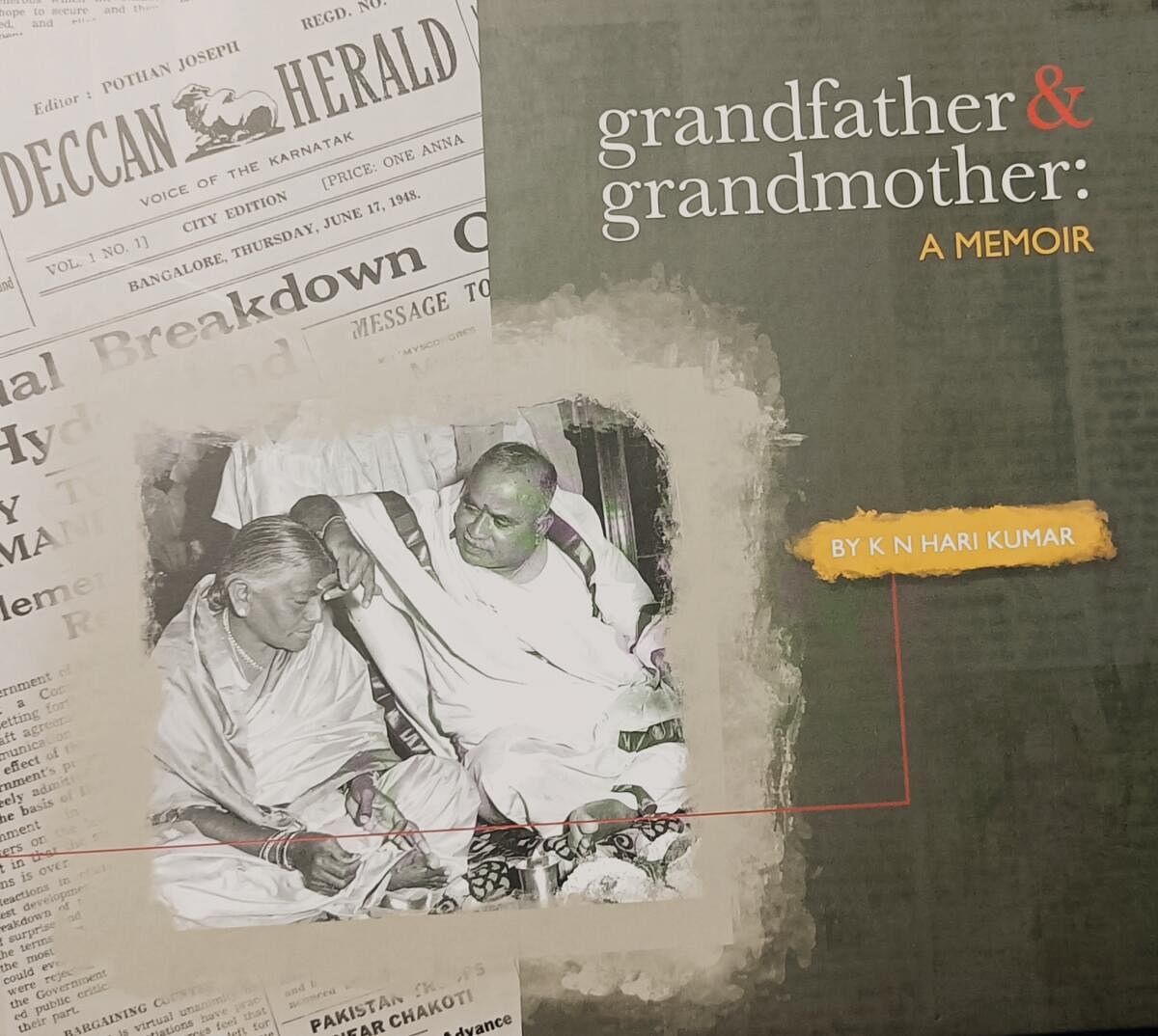

As a text, K N Hari Kumar’s Grandfather & Grandmother: A Memoir is much too brief. The little vignettes of the personal life of K N Guruswamy and the setting up of Deccan Herald are fascinating in themselves, but hardly sufficient to tell the story of a member of a somewhat distant local liquor-based elite finding a place of prominence in a city of newly independent India; a city that was soon to get global recognition. The paucity of text is made up by a collection of pictures, each of them meeting the journalistic requirement of being worth a thousand words. The net result — and perhaps all that Hari Kumar intended to do — is a set of pointers to an important story of post-independence Mysore that remains untold.

It is, at one broad level, the story of an elite seeking to protect itself against the vagaries that independence might bring. There was a new elite, including Reddy and Vokkaliga-led governments, that the old elite had to deal with. And beyond the intricacies of power politics, there was the possibility of Gandhi’s preoccupations, especially prohibition, influencing local policy. These uncertainties brought together an unlikely alliance of diverse interests that contributed to the coming of an English newspaper. Owned by an arrack contractor, prompted by the last Dewan of princely Mysore, managed at times by a long-standing frenemy of the owner and at other times by the head of the state’s Socialist party, and edited by one of the leading Indian editors of the time, the early years of Deccan Herald provide the ingredients for an epoch-making story that Hari Kumar chooses not to focus on.

A grandson’s memories of his grandfather may not be the best platform to speak about aspects that must have caused some discomfort within the family. Guruswamy’s ‘life-long friend’ Venkataswamy began with very little but had the managerial acumen to reach a position where he was to keep out from the institution members of Guruswamy’s immediate family. Hari Kumar does point to some elements of what happened but stops well short of exploring the fascinating interaction between ownership, friendship and family in a story that would have relevance for business houses elsewhere in the country.

In the midst of its social role, it is easy to forget the pioneering part Deccan Herald played in journalism of the time. If it did establish itself in the difficult domain of credible local English-language newspapers, it had much to do with the editorial skill of its first editor, Pothan Joseph. Back in the early 1980s, I had the opportunity as an academic-turned-journalist to rework the financial pages of Deccan Herald (Full disclosure: K N Hari Kumar was the editor at that time). As I traced the history of the paper’s financial pages, I saw Pothan Joseph’s pages in the 1950s, which were clearly far ahead of their times. It taught me not just what a good editor could do, but also, at the other end, what normal journalistic wear and tear could do to a paper.

Hari Kumar’s memories of his grandfather and grandmother that he chooses to make public are confined within the inevitable boundaries of personal relations. It provides us glimpses into the social and journalistic dynamics of the emergence of a media house that is sensitive to local concerns but stops just short of what would have been a fascinating picture.

The reviewer is Professor and Dean, School of Social Sciences and Head, Inequality and Human Development Programme at the National Institute of Advanced Studies, Bengaluru.