Majuli, in the heart of the mighty Brahmaputra, has long been known as the largest river island in the world although the fact has been challenged in recent times by an island in South America — Ilha de Marajóon on the Amazon in Brazil. But others point out that Majuli is the largest ‘inhabited’ river island in the world. Going beyond geographical comparison, what is more important is the island’s position as a unique cultural and socio-religious centre of Assam, as well as of India.

To reach there, one has to take a ferry from Nimatighat, a river port near Jorhat town in upper Assam. Now a plan to connect it with the mainland by a bridge is on the anvil.

In historical books, Majuli was mentioned as Ratanpur or Ratnapur, a place rich in agriculture which also served as a stopover for boats laden with goods sailing upstream and downstream. Those were the days when the river served as the main thoroughfare — both for ferrying goods and travellers.

Talking about the island, D Nath in his book, The Majuli Island writes, ‘…it is almost an island of the traditional Assamese life and culture. The indigenous art and crafts, the music and dance forms, and the food and dress habits of the indigenous Assamese have considerably survived the stresses and strains of time and circumstances in Majuli.’

Majuli’s lifestyle centres around the satras (monasteries) and their way of life in the best of Vaishnavite tradition introduced by Saint Sri Sankardeva (1449–1568). He was a guru, social reformer and creative genius all rolled into one. Unhappy with the excesses of ritualistic worship during his time, he set out to travel to pilgrimage centres in other parts of India at the age of 32. During his travels, he came across thinkers at the helm of the rising neo-Vaishnavism movement and took readily to its simple way of worship dedicated to Lord Krishna.

On his return, Sankardeva established a satra for the bhakats (followers). His disciples continued his tradition by opening more of them after his demise. Among many, the more famous ones are Kamalabari, Auniati, Gorumurah, Dakhinpat and Samaguri satras.

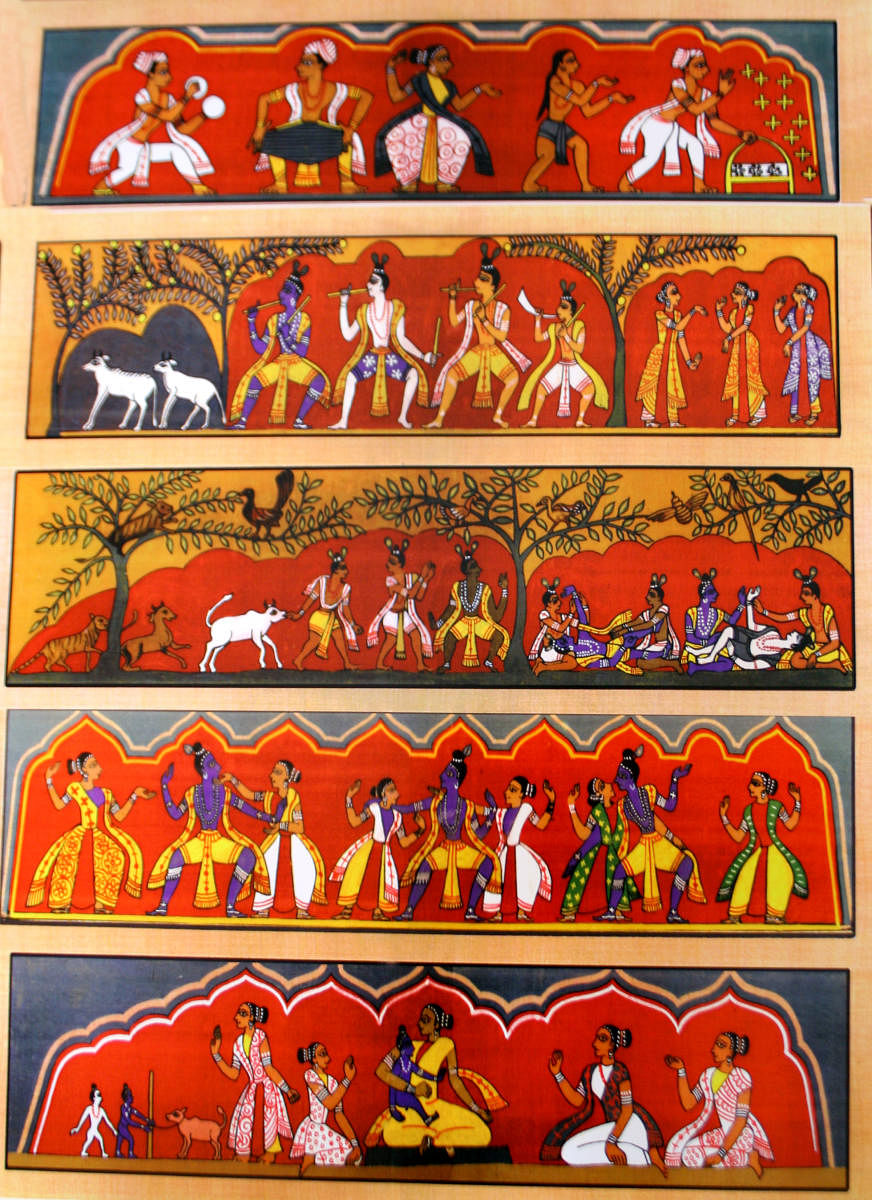

Sankardeva was a great artist too. To get across his message, he ingeniously used the medium of art and culture. This proved very effective as most of the people were illiterate but could easily relate to the performances and the message therein when presented visually.

He wrote plays on the life of Lord Krishna to be performed as bhaonas (traditional plays) in villages. They were mostly performed at the namghars, village prayer hall-cum-congregation centres.

However, namghars were not confined to Majuli alone. In Assam, even today, in every village or community, even towns and cities, namghars are found serving as community halls.

Sankardeva also composed devotional songs called bargeet setting them to classical ragas but interspersed with local elements. He choreographed dances (satriya dance) on aspects of Lord Krishna’s life. Satriya dance is now recognised in the pantheon of Indian classical dance tradition. He introduced percussion orchestras to attract the people. The big-sized cymbal, known as bhor-taal locally, was adopted from neighbouring Bhutan.

Disappearing heritage

The satra premises display beautiful wood-painted doors carved by a special artisans known as khanikars. They were versatile craftsmen equally skilful in painting, architecture, manuscript-writing and illustrating, mask-making and woodcarving. The intricately decorated objects like trays and pedestals, known as thogi, for keeping the naam-ghosa, the book of hymns in praise of Lord Krishna, bear testimony to the rich tradition of woodcarving in the land.

The bhaonas needed actors to put on masks to enact the roles — whether as Ravana, Garuda or Hanuman. Hence mask-making tradition also thrived using locally available materials like bamboo, cane and a special kind of clay. But today the art has all but disappeared. Only at the Samaguri satra, the family of Satradhikar Kosho Kanta Dev Goswami, a Lalit Kala Akademi winner, has continued to produce the masks in the age-old style.

Manuscript-writing, both with and without painted illustrations, on barks of saanchi trees and cotton folios (tula-paat), is another distinctive tradition of graphic art in Assam.

In olden times elephant tusk artefacts were common and Majuli had its own ivory craft tradition. Some of the samples like ivory combs and miniature boats can be seen at the museum at the Auniati satra.

Priceless manuscripts written on sanchi-paat, instruments used during the bhaona, indigenous masks, paintings on wood, huge utensils in brass and palanquins are displayed here too.

The island is also known for the beautiful hand-woven clothes, mainly mekhela-sador, the two piece ensemble Assamese women wear, produced by Mising tribe women. Sankardeva took into his fold all, irrespective of caste and creed, and the tribals (janajati) were equally welcome.

There is, however, some apprehension that the satras and the unique heritage will cease to exist eventually. Erosion has taken a toll on Majuli for decades and some experts say the island might disappear from the face of the earth altogether. But locals are steadfast in their belief that Majuli is going to survive as it did in the past and its unique culture will thrive on too.