Credit: Special Arrangement

Pablo Picasso’s ‘Guernica’ is often considered to be the most famous antiwar painting of the 20th century. The massive artwork, composed of dramatic and tragic larger-than-life figures, contorted faces and agonised animals, is approximately eleven feet tall and twenty-five feet wide.

Painted in 1937, Picasso’s ‘tableau of horror’ was a response to the Nazi bombing of the Basque town of Guernica during the Spanish Civil War. The blanket bombing on 26 April 1937 had brutally killed and injured many.

Picasso rendered the entire painting with a strikingly neutral monochrome palette to suit the mournful subject and to represent “distress, anguish, terror, insurmountable pain, massacres, and finally peace found in death.” He, however, did not provide a formal explanation of the artistic symbols or political meaning, leaving the artwork to speak for itself.

Over the decades, ‘Guernica’ has been interpreted and analysed in great detail by art critics and historians. It is generally seen as a universal statement about human suffering in the face of political violence; art against tyranny; and a howling mural against fascism. It was displayed in the Spanish Pavilion of the Paris International Exhibition of 1937. After the event, it came under the care of Picasso himself who insisted that it could travel to museums and institutions only for fundraising purposes for worthy causes.

Curiously, the initial response to ‘Guernica’ was discouraging. The Spanish and Basque governments detested the mural at the Paris Exhibition, while the German fair guidebook mocked it as “the dream of a madman, a hodgepodge of body parts that a four-year-old child could have painted.” Several artists too thought Picasso was just “shitting on Gernika.” Luis Buñuel, the Spanish-French-Mexican filmmaker said he would be happy to “blow up the painting”, while French philosopher and writer Jean-Paul Sartre wondered if the painting had “won over a single heart to the Spanish cause.”

Even when ‘Guernica’ was taken to Great Britain to raise funds for victims of the war and later to America to help the Spanish Refugee Relief Campaign, the response was lukewarm. It was only in November 1939 that the painting received extensive appreciation and acclaim. Displayed as the centrepiece at the ‘Picasso: Forty Years of His Art’ exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, the terrifying anti-war painting attracted thousands of people who lined up to see the show. The rest is history.

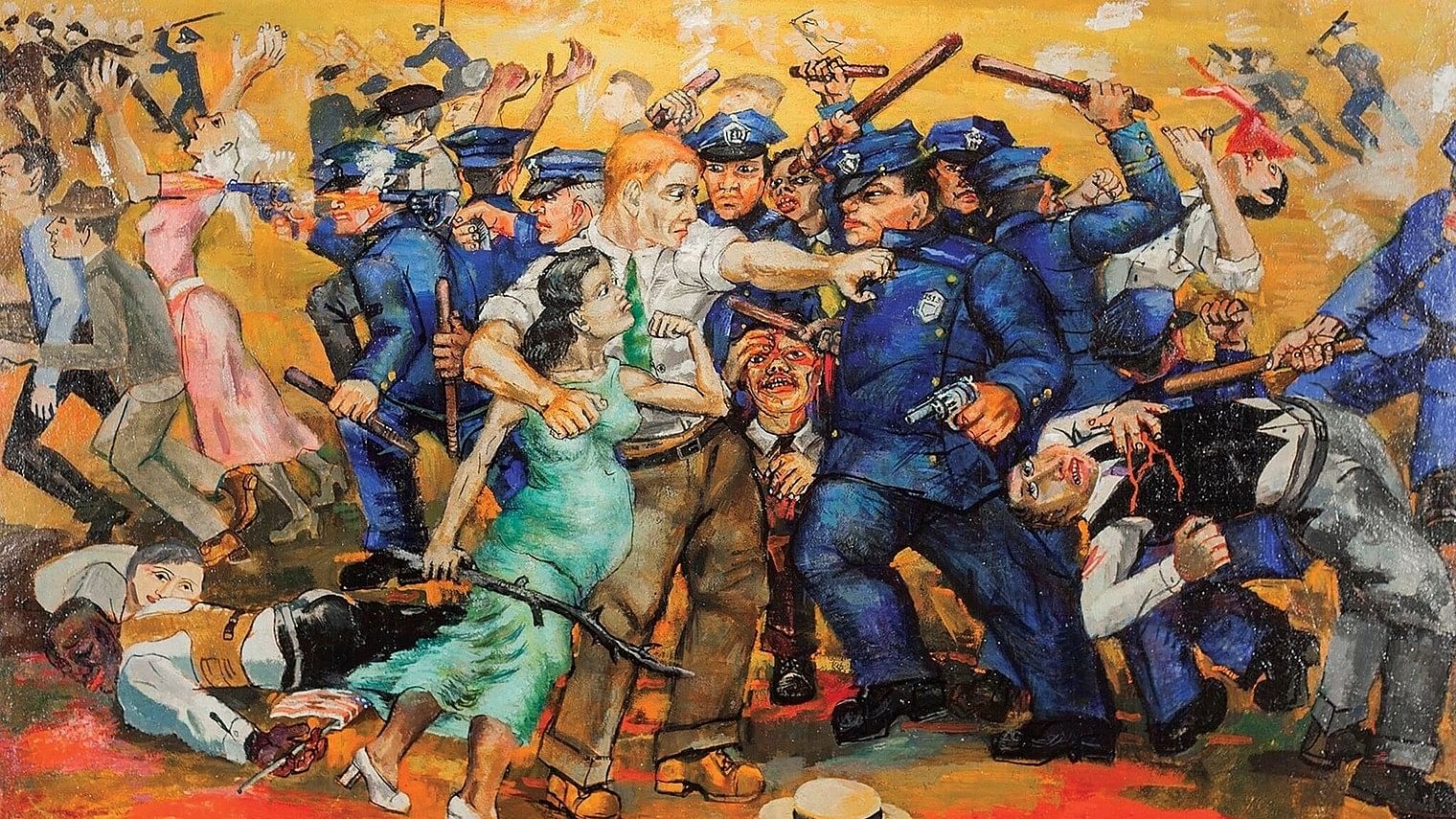

There are many ‘protest’ paintings; some that came before and many that were created after ‘Guernica’. American artist Philip Evergood’s work titled ‘An American Tragedy’ is one among them.

Painted in the same year as ‘Guernica’, Evergood’s radical and expressionist work depicted a violent clash between police and demonstrating steelworkers. At the centre of the 29×39-inch oil painting is an unarmed worker shielding his family and fellow union members from the onslaught of uniformed police personnel armed with batons and guns. A rebellious pregnant woman and a swarm of bleeding workers complete the aggressive picture.

The motivation for the ‘An American Tragedy’ painting came from the notorious ‘Memorial Day massacre’ which took place in South Chicago on May 30, 1937 (just about a month after the Guernica bombing). Evergood’s bold image, however, unlike Picasso’s ‘Guernica’, is rendered with rich colours.

Six months before the Memorial Day massacre, Evergood had personally experienced the brute power of police aggression. He was one among the hundreds of protesting artists in New York City who were beaten and dragged by the police. “My nose was broken, blood was pouring out of my eyes, my ear was all torn down, my overcoat had been taken and the collar ripped off, and they hardly recognised me when I was pushed out by the police,” recalled Evergood of the incident. “I don’t think that anybody who hasn’t really been beaten up by the police badly, as I have, could have painted ‘An American Tragedy.’”

Some historians find formal and compositional similarities between ‘An American Tragedy’ and Picasso’s ‘Guernica’. Both are seen to depict the violence of the times; aggressors attacking unarmed people; fallen figures; and in general, showing fierce aspects of ideological conflicts.

“Evergood’s depiction of police brutality resonates with contemporary images of fascist aggression in Europe,” writes art historian Dr Lara Kuykendall. “Thus, ‘An American Tragedy’ manifests Evergood’s fierce opposition to the menacing rise of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi party in Germany and the concurrent atrocities committed by Francisco Franco in Spain. This interpretation broadens the painting’s sphere of significance beyond the plight of American labour unions and inaugurates Evergood’s American worker as a global antifascist hero as well.”

Realist paintings

Born in New York on October 26, 1901, Evergood studied at Cambridge University, the Slade School of Art in London, the Art Students League in New York and Julien’s Academy in Paris.

He was among the group of prominent American artists of the 1930s who used everyday people as heroic figures. A well-known propagandist and social innovator, his reputation was established with realist paintings that underscored the plight of the common man.

An active member of the American Artists Congress, he served as president of the Artists Union in the mid-1930s. “I have painted more social protest paintings than anyone else in America,” he said in an interview. “I have devoted nine-tenths of my life to painting social protest paintings.” In later years, his paintings are said to have become less expressionist and more sober without losing their universal, humanist tones.