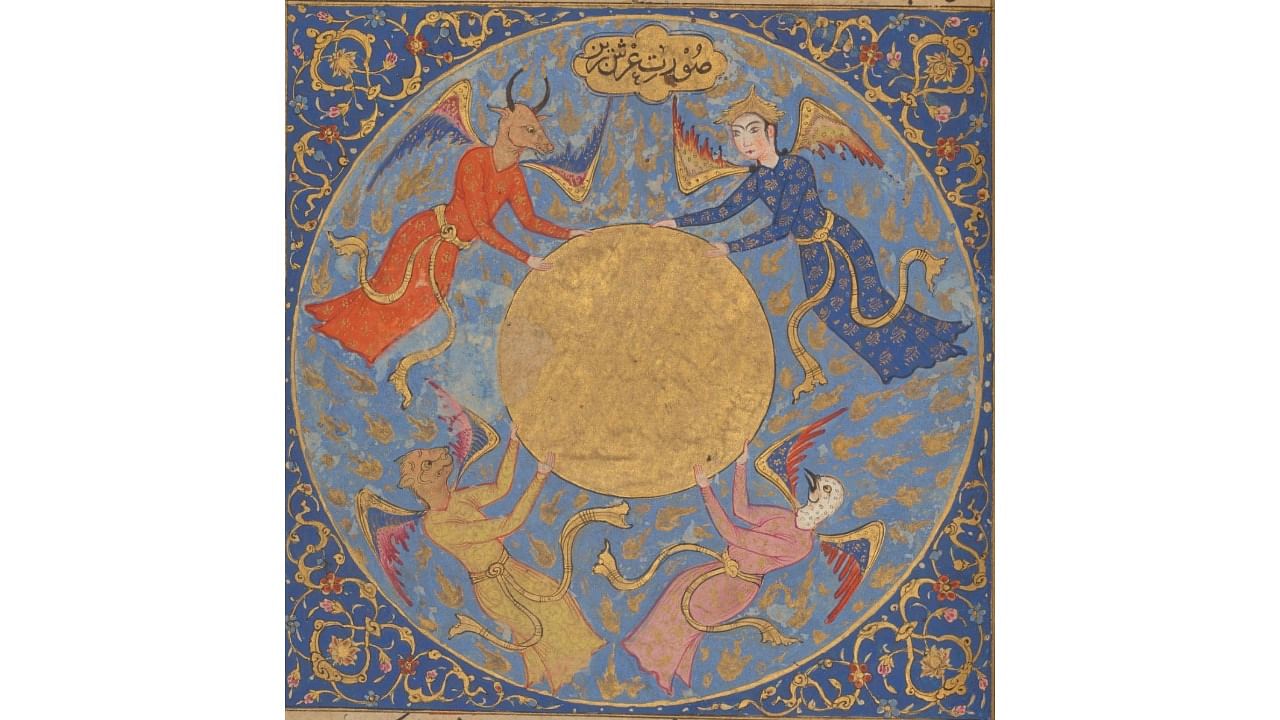

'The Four Throne Bearers', Nujum Ul-Ulum, Bijapur, India (1570).

Credit: Chester Beatty Library

Illustrating angels, celestial entities, planets, constellations, talismans and spells, the Nujum al-Ulum, or ‘Stars of the Sciences’, is a treatise on astrology, mysticism and their connections to kingship and power. Supposedly commissioned by Ali Adil Shah I of Bijapur in the late 16th century, it is one of the earliest-dated manuscripts shedding light on the rich painting traditions of the Deccan.

The Deccan Sultanates had long-held familial ties to Persian and Turkish states and were populated by both local Hindu and Muslim elites, along with emigres from Central Asia and Eastern Africa. This cosmopolitan culture and society of early-modern Deccan is replicated in the Nujum al-Ulum’s contents and illustrations, which draw on Islamic, Vedic and Indic knowledge systems and artistic traditions.

The manuscript contains nearly 800 illustrations that are adorned with materials such as gold and lapis lazuli, suggesting they were produced in a kitabkhana or courtly atelier. The scope of the treatise was ambitious: it was meant to cover astrology, medicine, war, elephants and horses, perfumes, gardening and culinary arts, among other subjects. It elucidates upon heavenly beings in Islamic astrology, northern and southern constellations, planets, zodiac signs and nakshatras (star groupings) of Indic astrology, spells for summoning spirits, objects associated with kingship, and 140 ruhanis, who were primarily female Hindu Tantric deities.

The text is addressed to a ruler, to enlighten him about the cosmic forces that can be controlled to enhance his authority and reign.

In its representation of planets and constellations, the Nujum combines Islamic and Hindu elements. For example, the anthropomorphised Mars has been conventionally depicted as a warrior in Islamic cosmological treatises; and so the Nujum presents it as the mythical Persian warrior Rustam, riding a ram. However, contrary to the norm, he has also been reimagined with multiple arms, one of them even bearing a trident, a symbol usually associated with the Hindu deity Shiva.

Similarly, the depiction of the Sun shows the figure in a chariot drawn by lions, but this personification also holds a conch and mace, objects associated with the iconography of the Hindu deity Vishnu. Elsewhere, in the section on objects surrounding an ideal ruler, the term chakravartin, which references an ideal ruler in Buddhism, Jainism and Hinduism, is used without explanation, suggesting that the term and its implications were common knowledge.

Scholars like Deborah Hutton and Emma Flatt propose that the deliberate inclusion of different knowledge traditions and sources in texts like the Nujum aimed to emphasise the shared vocabulary of ideas among patrons and courtiers. Understanding these varied systems not only helped rulers to retain culturally diverse and skilled courtiers but also allowed courtiers to educate themselves in, and grasp the significance of different iconographic systems. Moreover, it showcased the artists’ ability to craft multivalent messages, intelligible to their cosmopolitan viewers.

Whether intended for guiding esoteric practices or enlightening rulers on cosmological concepts, the Nujum al-Ulum, through its appropriation of ideas and aesthetic traditions from multiple references, serves as a testament to the syncretic visual and intellectual practices prevalent in the Bijapur court.

(Discover Indian Art is a monthly column that delves into fascinating stories on art from across the sub-continent, curated by the editors of the MAP Academy. Find them on Instagram as @map_academy)