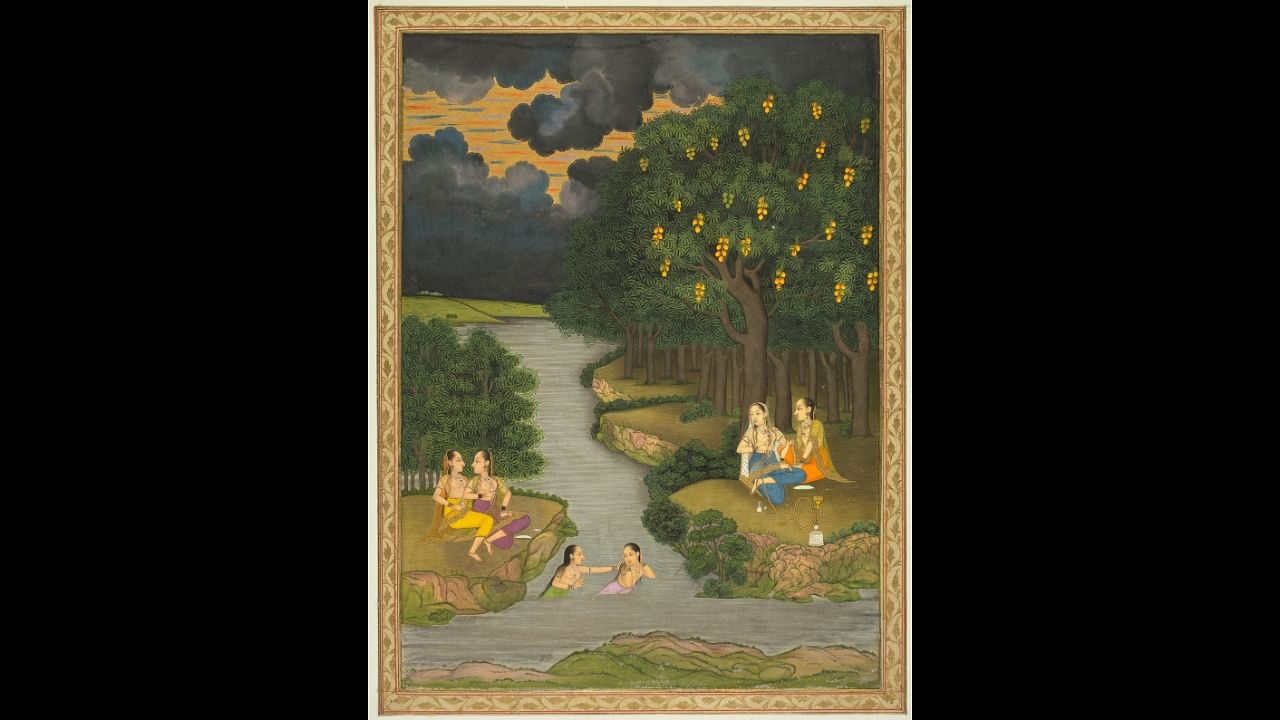

'Women Enjoying the River at the Forest', Hunhar II, India, 1765.

Pic courtesy: The Cleveland Museum of Art

Every region in India produces its own variety of mango. India is also the world’s largest producer of mangoes, but not a significant contributor to international trade since the Indian population consumes most of its homegrown produce. This abundance in the variety and scale of mango production and its significance in South Asian food practices has inevitably influenced art, politics and culture in India. The golden-yellow fruit, synonymous with summer in India, has become a symbol of wealth, a tool of diplomacy, an icon of sensuality, and an enduring metaphor for South Asia itself. A look at the various lives the fruit has led allows us to trace its vast and colourful history.

The luscious mangoes that we see today were small and fibrous when they were first domesticated 4,000 years ago. The Mughals, the Portuguese, and countless other communities improved the fruit through selective breeding. Babur, who pined for the melons, peaches, apricots and walnuts of Central Asia, came to admire the flavours of mango quite immediately. Akbar, Shah Jahan and Jahangir remained steadfast in their commitment to maintaining orchards and groves and securing their favourite variety of mangoes every summer. Mangoes appeared in miniature paintings with scenes from gardens, groves and poetry recitals — and mango picking promptly became a princely pastime. Early on, mangoes’ deep sweetness lent itself to representing desire and became a symbol of fertility and love, often occurring in paintings with young women at leisure, in groves as a setting for a scene or beneath a tree laden with fruits. Some miniature paintings announced the arrival of monsoons with dark clouds and mango trees.

The allusions to fertility and abundance, however, were not restricted to paintings. The mango tree, which is believed to be a kalpa-vriksha or wish-fulfilling tree, is depicted in Jain, Buddhist and Hindu literature and sculptures. A 12th-century sandstone sculpture of the Jain goddess Ambika shows her seated on a lion with a child under a mango tree, protected by yakshi, a nature spirit.

The eastern arched gateway at Sanchi Stupa contains a vrikshaka, or tree goddess, holding a mango tree above her. Kamadeva, the god of erotic love, desire and pleasure in Hindu mythology, is known to use an arrow tipped with mango blossoms to stir love.

Commodified representative

As religious and courtly depictions of the mango grew in South Asia, so did its status as a symbol of wealth and luxury.

If the exchange of mangoes is symbolic of the diplomatic relations between India and Pakistan today, Indian art is overripe with historical examples of mangoes presented as gifts or commissioned as luxurious artefacts. These include a 17th-century mango-shaped flask studded with gold, rubies, and emeralds; an 18th-century Mughal mango-shaped vessel made of silver and fabric; an 18th- or 19th-century mango-shaped kohl container covered in floral patterns and countless others. The manga malai, a mango-shaped pendant, often encrusted with rubies, and the mankolam and kairi, two saree motifs popular among the Kanjivaram weavers in Kanchipuram, Tamil Nadu, and brocade weavers in Varanasi (formerly Benares), are important metaphors of fertility, wealth and auspiciousness in bridal trousseaus.

The modern paisley pattern — which different communities believe derives variously from the almond, the cashew and a sprouting date palm — is supposed to have also been inspired by the mango in India. Interestingly, although paisley shawls became popular during Queen Victoria’s reign because of colonial trade, the pattern itself came to be associated with a major centre of production in Scotland — the town of Paisley, which became known as the cultural centre of the pattern by the mid-18th century.

The mango, however, was strictly South Asian still. In the 1990s, as new voices and stories emerged after the advent of globalisation, migration, seasonless eating and borderless trade, the mango became the most accessible and commodified representative of South Asia.

Subsequently, the reductive symbols of the Taj Mahal in Agra, henna-painted hands, and ripe mangoes also came to dominate South Asian identity in many creative industries. In the 2000s, book publishing, for one, was replete with examples of mangoes in book titles and on book covers — Mohammed Hanif’s novel A Case Of Exploding Mangoes (2008) and David Davidar’s novel The House Of Blue Mangoes (2002), to name two. In 2013, while receiving a Lifetime Achievement award, the writer Salman Rushdie repeated a piece of advice he apparently gives to every new South Asian writer about their book title, “No mangoes, no guavas”.

Discover Indian Art is a monthly column that delves into fascinating stories on art from across the sub-continent, curated by the editors of the MAP Academy. Find them on Instagram as @map_academy orwrite to them on hellomapacademy@map-india.org