Credit: Special Arrangement

Earlier this year, an unseen self-portrait of Norman Cornish (1919–2014), arguably the most famous artist from North East England in the 20th century, was discovered hidden behind another painting. The discovery was made by the Bowes Museum conservator, Jon Old, who was working on a Cornish ‘bar scene’ painting. Surprised to see a backboard set into the stretcher on the back of the painting, he removed the board to see if it was affecting the painting. “To my surprise, it revealed this wonderful other painting on the reverse, which was quite magical. I felt very privileged to have been the first person since Cornish to see this self-portrait.”

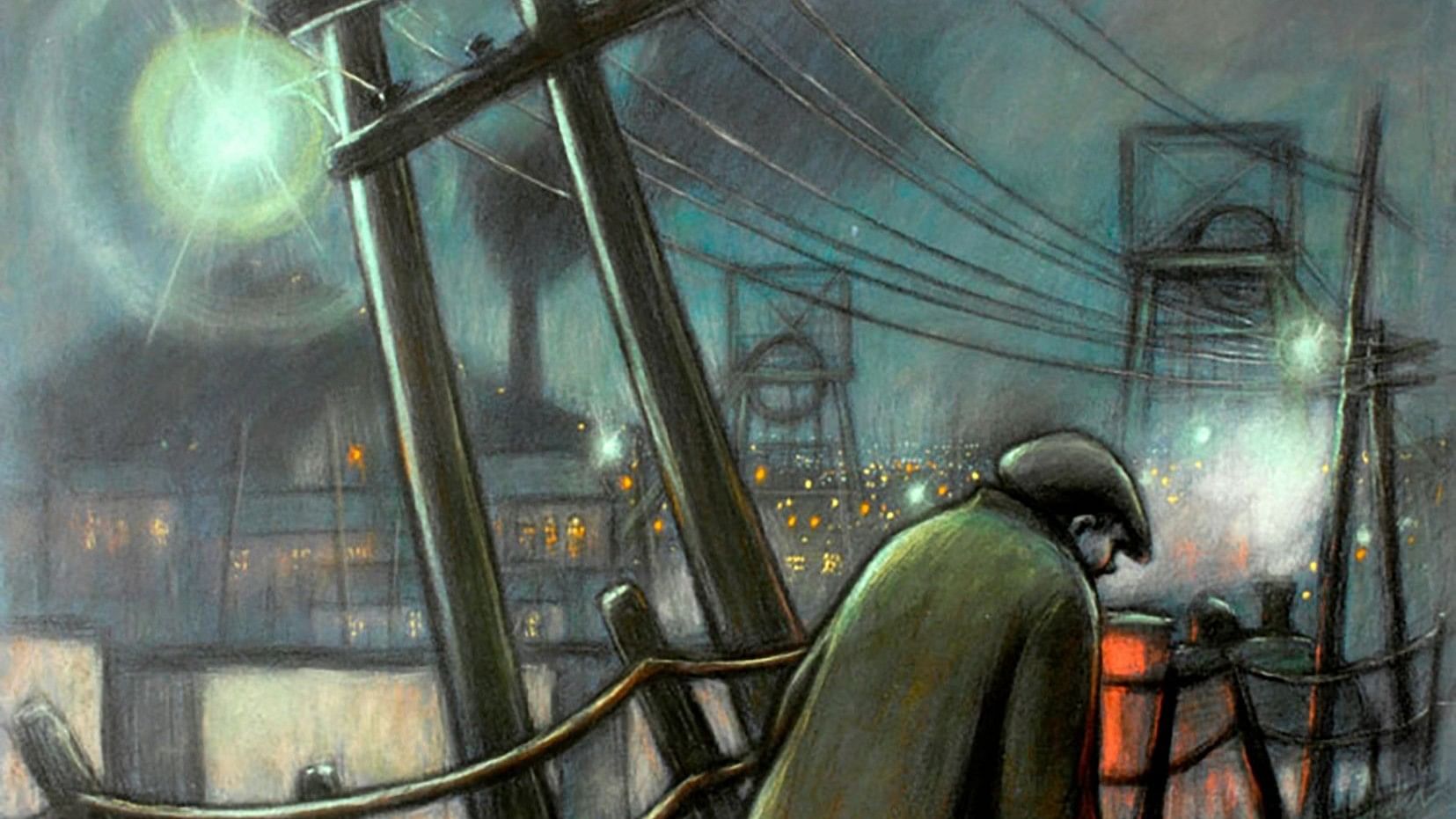

In a career spanning seven decades, Norman Cornish established himself as a popular and commercially successful artist in North East England. His depictions of mining life, notably in his home town of Spennymoor, captured many facets of the working class. His sensitive rendering of streetscapes, pub settings, and individual studies brought him fame and appreciation.

The prolific artist, who also painted self-portraits throughout his life, found meaning and symbolism in the forms and shapes of his chaotic surroundings. He was particularly attracted to fence posts, electric cables, lights, and telegraph poles. “All these poles thrusting up at the side of the road—they’re like a series of crosses, and sometimes I look at them as I walk along and they’re not telegraph poles anymore—they are crucifixes, and on every one of them there’s a miner hanging crucified.”

Humble beginnings

What distinguished Cornish from other artists depicting the coalfield was the fact that he was a miner as well. His position as an ‘insider’ within the community contributed significantly to his success.

Cornish, the eldest of seven children, had to quit school as a young boy. At 14, he began working as an apprentice at the Dean and Chapter Colliery to aid his family’s income. His work as a miner lasted 33 years. He chose to retire from the mines in 1966 due to chronic back problems.

While working as an apprentice lad, Cornish joined William Farell’s Spennymoor Settlement Sketching Club (The Pitman’s Academy). Farell recognised Cornish’s artistic talent and encouraged him to paint the mining scene as he saw and experienced it. Cornish strengthened his skills in figure drawing, perspective, and composition under Farell’s influence and instruction, all of which marked his subsequent work and established him as a sensitive artist. During the 1950s, his paintings were shown in major national exhibits, and his dedication to his close surroundings increased his local reputation.

Norman’s son, John Cornish, recalls how his father was different from other miners. “The vast majority of people of my father’s generation, who went to work, would have spent their leisure time going to the pub, racing and keeping pigeons,” says John. “My father was always walking around the town with a sketchbook and pen at the ready, sketching things. He didn’t set out to be a social historian. He was attracted to humanity and was simply painting the world around him.”

Collecting moments

In her thesis titled ‘Changing Landscapes: Norman Cornish and North East Regional Identity’, historian Leanne Bunn divides Cornish’s art into four main themes: the environment in which he lived and worked; the streets, which acted as the hub of community life; the pub environment and the character and detail of the faces absorbed in a game of dominoes; and the intimate portrayal of his family life.

Cornish worked with oils, watercolours, pastels, and charcoal. He made rapid sketches using a Flowmaster pen and filled his sketchbooks with preliminary drawings that served as the basis for larger works completed in his studio at home. “He was very good at collecting unguarded moments as opposed to posed shots—a man up a ladder, a man with a bicycle, anything,” says John. “That was his workspace, really, the sketchbook.”

Cornish acknowledged numerous artistic influences, including the works of Rembrandt, Vincent Van Gogh, Edgar Degas, Henri Toulouse-Lautrec, and Paul Cézanne. “I have resisted being swamped by their influences,” he wrote, “instead utilising their influences as an education in mental and visual awareness.”

Sid Chaplin (1916-1986), a co-miner, author, and lifelong friend, once described Cornish as a ‘mystic with a total grasp of what makes matter vibrate, from coal to colliery rows, from the workings 1,500 feet below ground to the bus stop and the chapel at the end of the street. In himself and his work, a prime example of being with it and staying with it.’

Cornish had his fair share of criticism. He was accused of presenting working-class life in a romanticised manner, as well as a consoling and soothing representation of his society, ignoring the tensions caused by hardship, toil, and poverty. Cornish was also not known to hold any strong political beliefs. Throughout his career, he avoided strong political associations. Notably, he made no artistic mention of the pit closures, strikes, and overall downfall of the industry in the 1970s and 1980s.

When he died on August 1, 2014, at the age of 94, Cornish was the last surviving artist of the legendary Pitman’s Academy at The Spennymoor Settlement.