Credit: Special Arrangement

The unique cultural and linguistic identity of South India has always been a source of tremendous pride for the entire country. Tracing its artful genesis, DAG recently inaugurated its second edition of Madras Modern: Regionalism and Identity, mapping the Madras Art Movement from its inception to its flowering in the second half of the 20th century.

The skilful curation of artworks by 32 stalwart artists showcased the elements that shaped the Madras Art Movement and the Cholamandal Artists’ Village. It spotlighted the dimensions this journey assumed through the pivotal role played by women artists in the Madras Art Movement, a late phenomenon within the national context.

The Government College of Fine Arts (the birthplace of the Madras Art movement) was set up in 1850, and flowered under the guidance of the first Indian artist-principal, DP Roy Chowdhury who did away with the colonial templates in the explorations of human forms. His gripping rendition of the sculpture When Winter Comes is a masterpiece: A startling expression of human artistry. Each wrinkle and fold in the pickled skin of the old man, and the overlapping toes of the forlorn figure weighed down by the sheer despondency of life linger forever in the mind of the viewer.

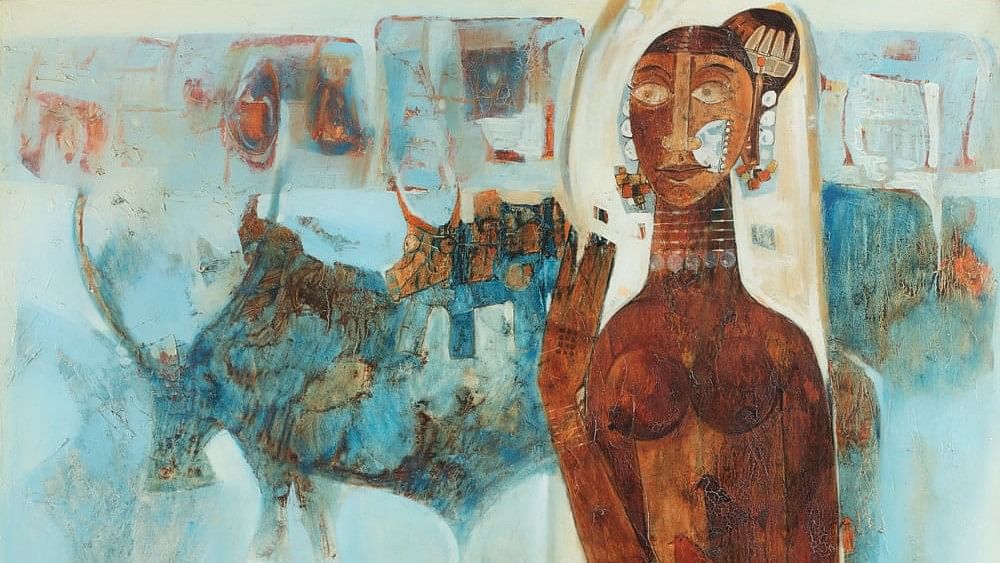

After Chowdhury, under the tutelage of pioneering artist KCS Panicker, the movement developed momentum once he became the principal of the Government College of Fine Arts in 1958. Panicker dipped into the rather intriguing Hindu horoscopes, and mythology to mould his own signature style. Sultan Ali took to developing the idiom of Indian art under the tutelage of Choudhury, in a way that was a marked departure from the palaver of European art. He delved into Hindu mythology, absorbing the nuances of worship in the local community, bringing iconography into his works, and making use of techniques he imbibed from folk artists. Bhaskaran and Haridas explored the fascinating realm of neo-tantric motifs.

The muted reds and earthy browns appear to lend a voice to Bhaskaran’s artworks replete with geometric runs as if vocalising the tacit presence of the surreal in the environment in oil and encaustic. Chowdhury’s bird of the night in The Sentinel looks upon you with a brooding gaze; Redeppa Naidu’s Crucifixion girdles the form of god and the inky watercolour spurts in Ramanujam’s subconscious replay fight with myriad thoughts. The bronze contours of S Dhanapal’s Village Deity speak volumes, recalling Christ composed of geometric abstractions rooted in tribal and folk art.

Madras Modern bookmarked the sheer importance of the South Indian narrative as it evolved steadily through the works of artists and sculptors including L Munuswamy, S Dhanapal, R B Bhaskaran, P Gopinath, P V Jankiram and S Nandagopal. The 1960s further brought in the blending of local aesthetics with traditional expressions and thus it evolved into a seminal movement: a regional art grammar, inscribed within the larger context of Indian Modernism.

Says Ashish Anand, CEO and Managing Director of DAG, “In the attention that was paid to the dominant art centres elsewhere in India, Madras remained a sideshow even though its contribution has been no less significant than the Bengal School or the Progressives. In drawing our attention to regional imagery as part of its modern-speak, its contribution to our collective national heritage has been overwhelming. Its artists deserve a greater national presence.”