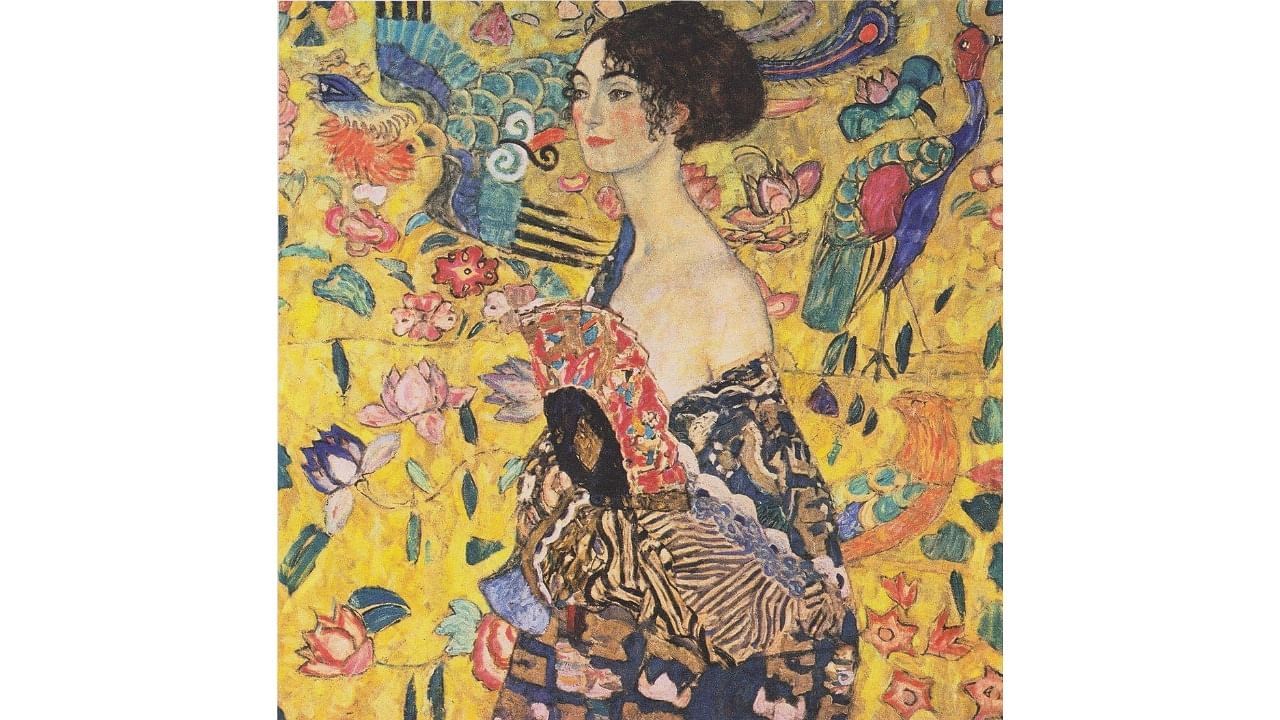

‘Lady With A Fan’ sold for £85.3 million ($108.4 million) at Sotheby’s in London, making it the most expensive work of art ever auctioned in Europe at that time.

Recently, a long-lost painting by Gustav Klimt (1862–1918), titled ‘Portrait Of Fraulein Lieser’, was rediscovered in Vienna. The 31-by-55-inch portrait, showing a young woman against a vivid crimson backdrop, was reportedly painted in 1917, a year before the artist’s death. Believed to be owned by Henriette Lieser, who was deported and killed by the Nazis, the painting was put up for auction last week, by the ‘im Kinsky Auction House’ in Vienna on behalf of the Lieser family. Ultimately, an unidentified bidder from Hong Kong acquired the artwork for US$32 million. Despite falling short of the estimated value of US$50, the painting set a new Austrian art auction record.

In the past, Gustav Klimt’s paintings have garnered global attention due to their historical significance and emotional resonance and commanded very high prices. Most notably, in June 2023, his painting ‘Lady With A Fan’ sold for £85.3 million ($108.4 million) at Sotheby’s in London, making it the most expensive work of art ever auctioned in Europe at that time. Both ‘Lady With A Fan’ and ‘Portrait Of Fraulein Lieser’ were reportedly found unfinished on Klimt’s easel when he died of pneumonia on February 6, 1918, at the age of 55.

Distinctive style

By all accounts, Klimt was one of Vienna’s most sought-after portraitists of his time. A leading figure of the Vienna Secession, his intricate paintings mesmerised wealthy patrons and influential collectors. Incorporating ornamental patterns, decorative motifs, and symbols, Klimt pioneered a distinctive style focused exclusively on portraying sensuous women. “He paints a woman as though she were a jewel,” noted one of Klimt’s contemporaries. “She merely glitters, but the ring on her hand seems to breathe, and her hat has more life in it than she. Her mouth is like a blossom, but one does not imagine it can talk—yet her dress seems to whisper.”

Unlike his contemporaries, Klimt never created portraits of men or of himself. “I have never painted a self-portrait. I am less interested in myself as a subject for a painting than I am in other people, above all women...There is nothing special about me. I am a painter who paints day after day from morning to night...Whoever wants to know something about me... ought to look carefully at my pictures.” When selecting models, Klimt was highly discerning, favouring both high-society women as well as prostitutes. His deliberate, painstaking, time-intensive painting method immortalised these carefully chosen subjects in his work.

Historians and scholars note an eclectic range of influences contributing to Klimt’s distinct style, including Egyptian, Minoan, Classical Greek, and Byzantine inspirations. Klimt was also inspired by the engravings of Albrecht Dürer, late medieval European painting, and Japanese Rimpa school. He had an impressive collection of East Asian arts and crafts, precious textiles, kimonos, graphics and porcelain.

Klimt’s works were controversial because of the sensual depiction of the female form and intimate poses between lovers. This unsettled the traditional values of his era. His most iconic painting, The Kiss (1907-08), shows an embracing couple kneeling in a field of wildflowers. The artist contrasts the woman’s flowing, floral dress decorated with circular biomorphic forms with the man’s robe filled with strong, rectangular shapes and patterns, highlighting differences between the feminine and the masculine. With added gold, silver, and platinum flashes, the monumental 1.8 by 1.8 meter oil painting encapsulates Klimt’s distinctive style.

Art with science

Eric Kandel, an Austrian-born American neuroscientist, claims that Klimt found inspiration in science, read Darwin’s work, and became enthralled with cellular structure. “He began to look in a microscope and became fascinated with cells, with sperm and eggs, and incorporated them into his paintings.”

The Nobel Laureate argues that Klimt had remarkable insights into female sexuality. “He appreciated that women had an independent sexual existence from that of men, and understood that sexuality is not a pure drive that always exists by itself, but can be fused with aggression.”

While decorating his paintings with brilliant colours and ornamental devices, Klimt was keen to go beyond the surface.

“He did not follow the rituals of Western art or Freud’s naïve and incorrect teachings about female sexuality,” observes Kandel. “Rather, he wanted to use his own insights, which were extensive, to give a modern view of women’s sexuality: that they are capable of pleasuring themselves — they do not need the attention of a man, and their sex lives are just as rich as that of men.”

While Klimt’s artwork and philosophy have garnered much admiration, they have also faced scepticism and criticism. “Klimt’s practices strike me as domineering male voyeurism and sexual abuse,” observes Eliza Goodpasture in The Guardian.

“His disdain for women’s interior lives and fascination with their bodies is so pronounced it is almost a caricature of misogyny. Many of his paintings treat women as decorative, just like his elaborate gilded backgrounds and dresses, or as sexual objects. Like many modernist male artists, Klimt’s attitude towards women is central to his art.”

In his personal life, Klimt was shy and withdrawn. Though active sexually, he kept his affairs discreet and avoided personal scandal. He travelled little, kept no diary, and shunned other artists socially. Mainly devoted to his art and family, he lived in a modest rented apartment until his death.