Credit: Special Arrangement

Richard Serra passed away on 26 March this year, aged 85. He was known for his monumental and awe-inspiring yet introspective sculptures that challenged the viewer’s perception of space and materiality. His works blurred the boundaries between art and architecture while engaging audiences on a deeper level.

Art, for Serra, was a provocation. For him, artistic expression was a critical instrument that shaped our understanding of different cultures, feelings and emotions. The contentious sculptor of oversized yet minimalist metal works did not see himself as a political artist. “But anything I can do to make a difference, I will. America is a right-wing country, and I’m essentially from the old left.”

Born in 1939 in San Francisco, Serra was the second of three sons to a Spanish mother and a Russian-Jewish father, who worked as a shipyard pipe fitter. “My childhood was a happy one. I had an extremely loving mother and father. I came from a very poor background, but my mother understood my need to draw. She was Jewish. In some ways, she preordained what I was going to become.”

Serra studied in Berkeley and Santa Barbara from 1957 to 1961. After graduating in arts, he completed further studies to obtain a Master of Fine and Liberal Arts degree. In the early 1960s, he was a student of the German-American painter and designer Josef Albers at the University of California and Yale University in New Haven. Albers’ core teachings included learning to see things anew, developing technique through eye-hand coordination, and working with everyday objects. Albers repeatedly told his students: ‘Let the material express itself.’

Engaging with space

In 1964, Serra travelled to Paris with his friend Philip Glass. The works of Constantin Brâncuși and Alberto Giacometti, two of the most influential sculptors of the 20th century and pioneers of modernism, inspired him. Serra made regular visits to Brancusi’s studio and developed a strong admiration for Giacometti. “Brancusi and Giacometti showed me the many possibilities for engaging with space in new ways,” he reflected. “Giacometti proved working as an artist daily was a struggle. He epitomised the notion of existential dictate in sculpture.”

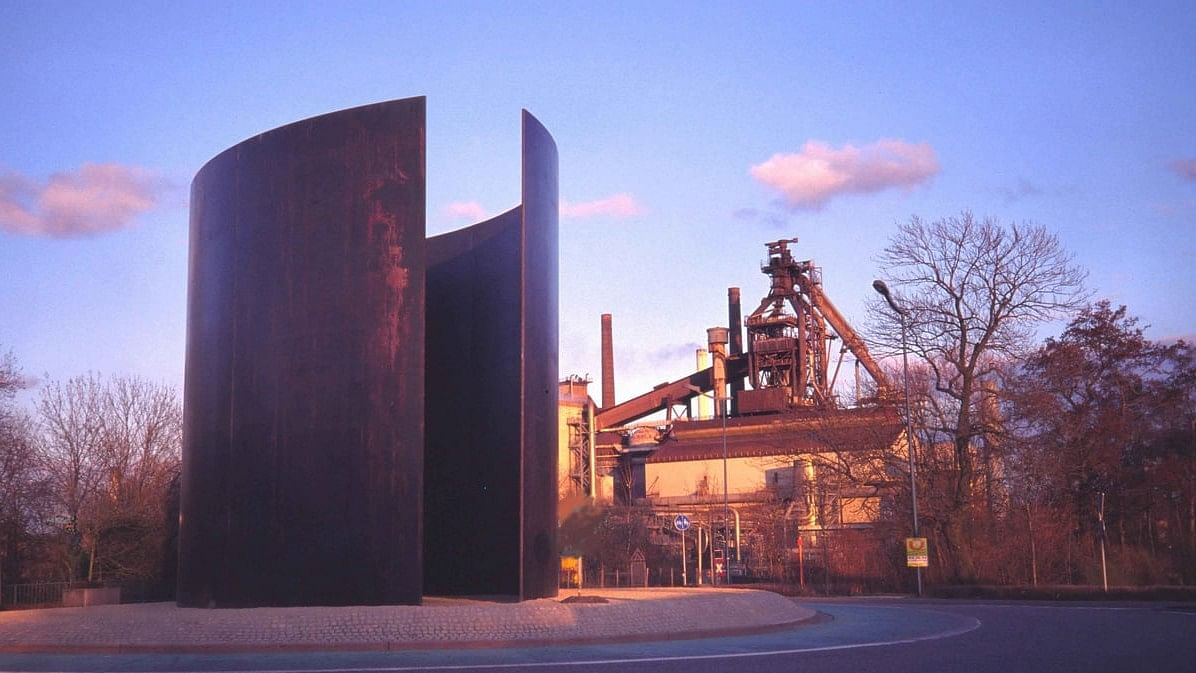

From 1968 onwards, Serra created monumental sculptures from solid materials like steel and iron, relying primarily on weight and gravity for balance. In addition to sculpture, he worked in printmaking, drawing, video, and film. He received a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1970, followed five years later by the ‘Sculpture Award’ from the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture.

Serra’s iconic public sculptures include ‘Tilted Arc’ (1981), a major commission for a federal building plaza in Lower Manhattan near New York’s City Hall. The imposing 15-ton, 124-foot-long, 12-foot-high curved rusty steel wall was designed to provoke thought and conversation among passersby. However, after initial acclaim, Tilted Arc sparked controversy when residents and workers began complaining that the sculpture clashed with the surrounding architecture and disrupted the visual harmony of the place. They also identified logistical challenges and highlighted safety concerns. This prompted a heated debate among the stakeholders.

With growing public outcry, a panel was formed in 1985. It recommended relocating the sculpture to the Smithsonian in Washington DC. Serra objected. He claimed that Tilted Arc was a site-specific work and, hence, could not be moved. After years of dispute, the controversial sculpture was dismantled in the dead of night on 15 March 1989 and carted off to a Brooklyn storage yard, ending its contentious saga.

In 2000, Serra created Charlie Brown, a 60-foot sculpture honouring Charles Schultz and his beloved Peanuts comic strip character. In 2005, Serra completed his most famous work, The Matter of Time. Comprising a series of steel sculptures, the expansive, walk-in installation led viewers through a labyrinth of twisting, turning forms. The weathered steel surfaces reflected light and shadow, creating an ever-changing visual experience that demanded contemplation and reflection.

As one of the largest sculptural commissions ever developed for a specific space in the history of modernism, the work cemented Serra’s reputation. Eminent art critic Robert Hughes hailed Serra as ‘not only the best sculptor alive, but the only great one at work anywhere in the 21st century.’

A daily drawing regime

Serra believed that people were different from one another because of their memories, expectations, origins and conditions. He wanted people to look at alternative perspectives and experiences offered to them. He was not interested in others copying his work, “but rather in people having an experience that is private and singular.”

For all his work on a monumental scale, drawing remained Serra’s primary means of experiencing and understanding the world from a young age. “I find drawing totally refreshing. In my sculpture and construction, drawing assists my vision in shaping form.”

In his final years, the 85-year-old art legend reportedly focused on a daily drawing regime while keeping his battle with cancer private. Paying tribute to the legendary man of steel who died in his home on Long Island, The Guardian art critic Adrian Searle wrote: “Serra could make you feel the weight of things and the spaces in between them.”