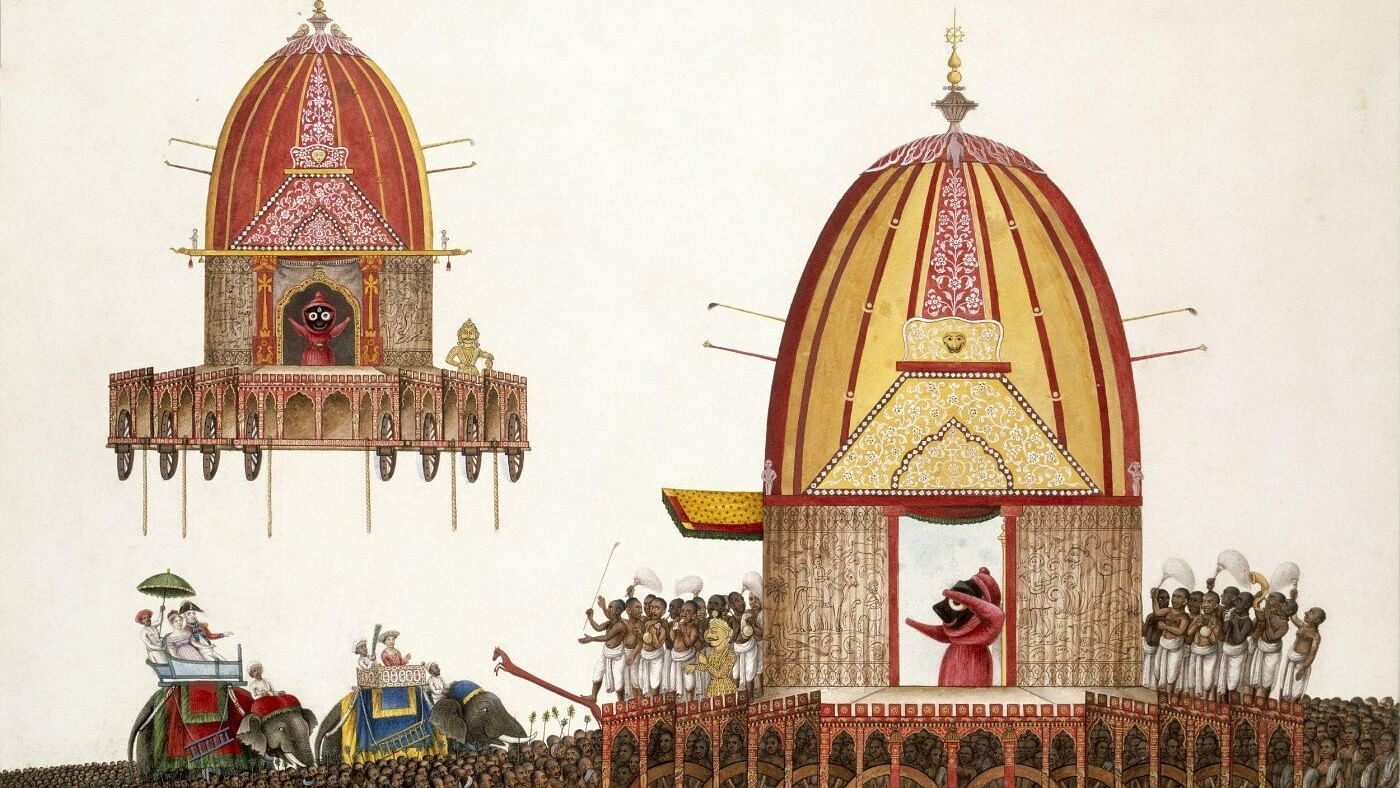

Rath Jatra, Puri (1820-22).

Photo credit: V&A

Every year, the gods set out on journeys. From Himachal Pradesh to Tamil Nadu, deities and their mythical family members often don lavish garments, jewels and royal insignia to leave the hallowed precincts of their temples in ornate palanquins or chariots. They are accompanied by oracles, fly-whisk bearers, dancers and musicians playing trumpets, drums and longhorns as well as millions of devotees who wait their turn, hoping to catch a glimpse of the idols.

Carnivalesque processions such as the rath yatras — or journeys in chariots — are part of yearly Hindu temple festivities in many parts of South Asia. Although contemporary rath yatras are predominantly associated with Hindu festivals, their historical roots extend beyond a single community. Faxian, a fifth-century Chinese monk and traveller, recorded witnessing 14-day chariot festivals in the Buddhist regions of Khotan (present-day China and Tajikistan) and Pataliputra (present-day Bihar, India), where gold and silver idols of the Buddha and Bodhisattvas were carried by devotees from peripheral monasteries to the city centre. He notes that royals and other courtiers took part in the festivities as the procession progressed through the streets.

In parts of the Indian subcontinent, such processions have been traced to the sixth–seventh centuries CE, when the Bhakti Movement popularised the idea of deities as living beings. It is widely believed that as the deities progress through the city along designated pathways, in their vehicles, they extend the sacred geography of their domain beyond the physical confines of the temple walls. The logic of a yatra is also intrinsic to the concept of worship in Hinduism. In temples and other places of worship, devotees undertake a parikrama — a clockwise circumambulation around deities — and perform rituals to seek blessings.

One of South Asia’s biggest temple chariots is part of the Thiruvarur Therottam, a temple chariot festival associated with the Thyagaraja Temple in Tiruvarur, Tamil Nadu. During this festival, Thyagarajaswami, who represents Shiva, is adorned and taken with his consort Kondi, an avatar of Parvati, for a day-long procession to bless devotees. Moreover, the Valluvar Kottam, a temple chariot that serves as a monument to the classical Tamil philosopher and poet Valluvar, is an example of how these chariots are also symbols of reverence for historical and mythical figures in South Asia.

Today, one of the largest rath yatras takes place in India in Puri, Odisha, where thousands of devotees jostle to get a hold of the ropes pulling Jagannath’s chariot. During the festival, which lasts for nine days during the monsoon months of Ashadh, Jagannath — an avatar of the Hindu god Vishnu — his brother Balabhadra and sister Subadhra are taken to the Gundicha Temple in the city and brought back to the Jagannath Temple after a week. The very act of pulling his chariot during this journey is considered auspicious; one that frees devotees from the cycle of death and rebirth and allows them to traverse a higher realm of consciousness.

Thus, a literal journey for the deities translates into a spiritual journey for their followers.

Discover Indian Art is a monthly column that delves into fascinating stories on art from across the sub-continent, curated by the editors of the MAP Academy. Find them on Instagram as @map_academy