Credit: Special Arrangement

What could a teeming Indian metropolis spread over 700-odd sq km have in common with a little island in Scotland, home to about 60 people and noted for its birdlife? I'm at the Science Gallery Bengaluru (SGB) in Sanjaynagar, at its showpiece opening exhibition CARBON, piecing together a story from dramatic photographs of skies in Bengaluru and Fair Isle.

The mediator tells me about the French artist Anais Tondeur and her journey from Fair Isle to the port town of Folkestone in southern England, a distant source of industrial soot — these particles were carried by winds over hundreds of miles, eventually smudging the skies of Fair Isle. Atmospheric scientists Rita van Dingenen and Jean-Philippe Putaud helped the artist measure the severity of the pollution at the photographed locations. Tondeur used carbon black particles on the face mask she wore to make the printer ink that produced the photographs.

In Bengaluru, she repeated the exercise with a group of volunteers, on a walk from the Indian Institute of Science to Sankey Tank. “In a sense, the pollution from these places is here, in the images,” says the mediator.

CARBON traverses ideas around the life-forming element in multiple artistic styles. It tries to speak with the viewer in an immediate, sensory space that makes themes of global consequence more accessible. Some questions prod more than they seek to resolve, all of them integral to the 35-plus exhibits. They are framed in a curatorial style that places the viewer right in the middle of the subject, making the engagement more personal than it is with the familiar, rigour-prone forms of science communication.

Triggered by Motion puts together a year’s data from 21 conservation projects in different parts of the world into 20-minute films, to understand how climate change is disrupting patterns of wildlife. X-Carbon, an arcade game, is set against a collapsing star and a civilisation it threatens to wipe out. Whale Falls, Carbon Sinks is an audio-visual installation on the natural-cultural history of whales that also lets me catch a whiff of the ocean, in a custom perfume.

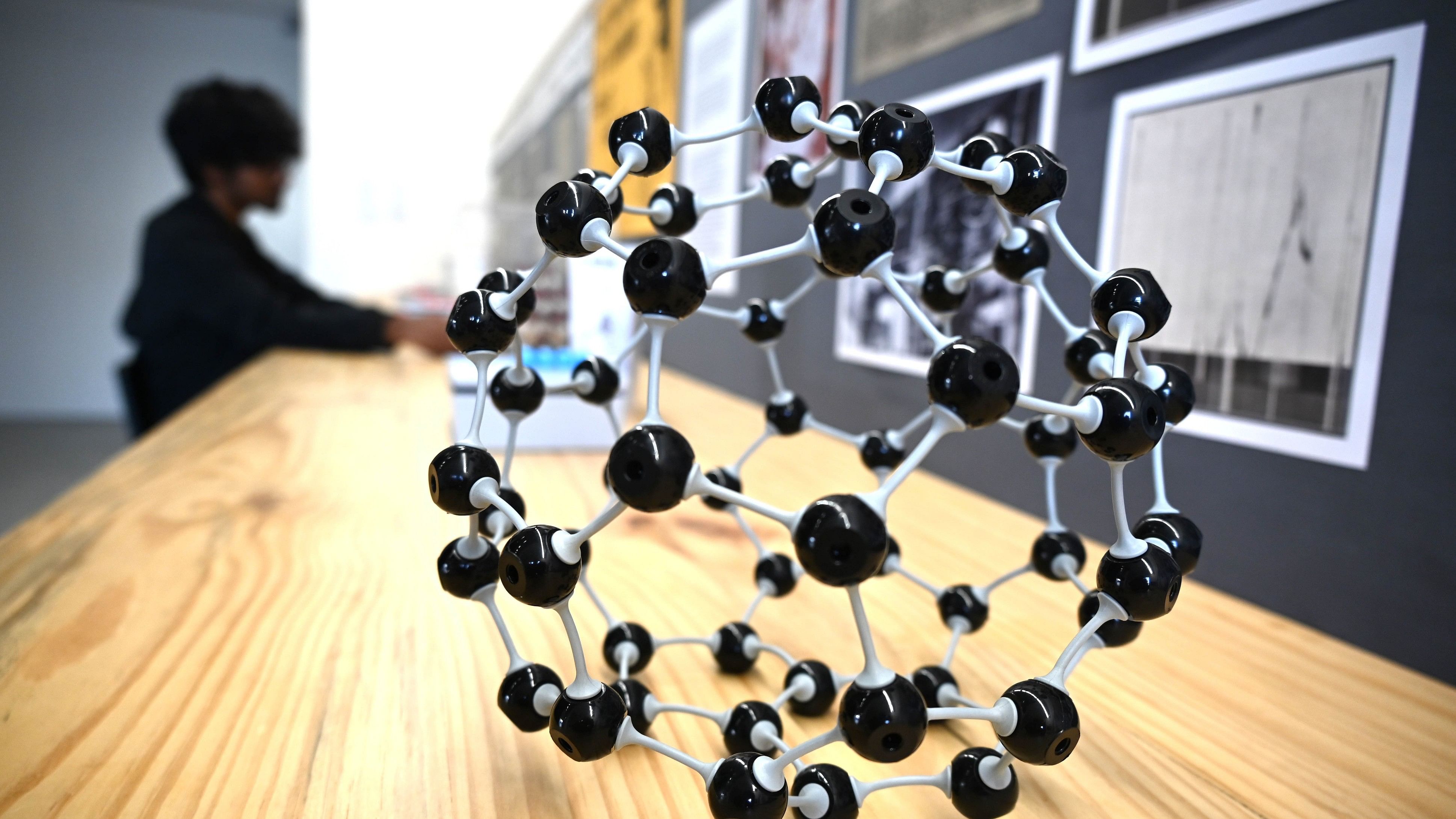

A virtual reality-powered exhibit lets me navigate complex carbon structures at the nanoscale. Then, I put the headphones on to listen to The Mineworkers’ Song, a 1950s composition by mineworker and playwright Pillo Deshwal, from the coalfields of Jharia in Jharkhand — this is a companion piece to images and text that also memorialise miners who have died in work accidents.

Jahnavi Phalkey, Director, SGB, says the choice of CARBON as the gallery’s first exhibition is informed by a desire to get the public to understand the relevance of research and to get them to say interesting things back to the researchers. “Carbon becomes among the most obvious choices because climate change is a key concern but then, doing an exhibition on climate change is like telling the public — here is the problem, and this is what you need to understand. There is a fatigue that comes from being asked to engage with research on terms that are set elsewhere. Simplification might not be the best approach because people are capable of understanding complexity if it is phrased in a language that is accessible to them,” she says.

There is the intention to discard broad-stroke narratives on carbon as the antagonist that needs to be controlled/sequestered and to frame positive discussions that help look at the problem in more interesting ways. The language of the exhibition stays true to this relatability of form, even when it tries to break the more abstract ideas down.

The energy slave, a concept architect-futurist R Buckminster Fuller introduced to equate energy generated by fossil fuels to volumes of human labour, finds expression in the exhibit Energy Slave Tokens. It has on display tokens, or weights made of bitumen that are equivalent to specific quantities of time spent on physical labour — hour, day, week, month, year, a lifetime.

Jahnavi underlines the cultural work being done at the gallery which opened in January this year — “Cultural work does inform policy-making but it will take time”.

SGB is preparing to host its next large exhibition, themed on quantum. CARBON has been a statement of intent from the gallery, a concerted attempt to steer local contexts — from Chhattisgarh to Buenos Aires to western Siberia — to shape a collective global expression. “It is a problem that needs to be addressed at a global scale because it is operating without boundaries. This is not something you can engage with by taking national borders to be real,” Jahnavi says.

CARBON is on at SGB till June 2024. The gallery is closed on Mondays and Tuesdays. Entry is free.