Thevan Pulayan once had a strong body, gleaming in its blackness. There was vigour in his body, and a passion in his eyes. He lived for the land, and the land watered by his sweat, thrived. While other fields had weedy crops, his’ were “thick and rich, as tall as a man”. For, isn’t it true that a “field sown and watered by a Pulayan is a festival for the eyes”? Now he is old and weakened. For the past 60 years, never had the crops once failed. But here he was, scanning the sky for rains that had failed once again, and frustration sat like fire in his chest. Not only are the rains fickle. The landlord is no better. It is Thevan Pulayan’s back-breaking labour that had made Narayana Nair’s wealth grow. A dog would have been grateful, but Narayana Nair is only human. On a whim, he turns Thevan Pulayan out.

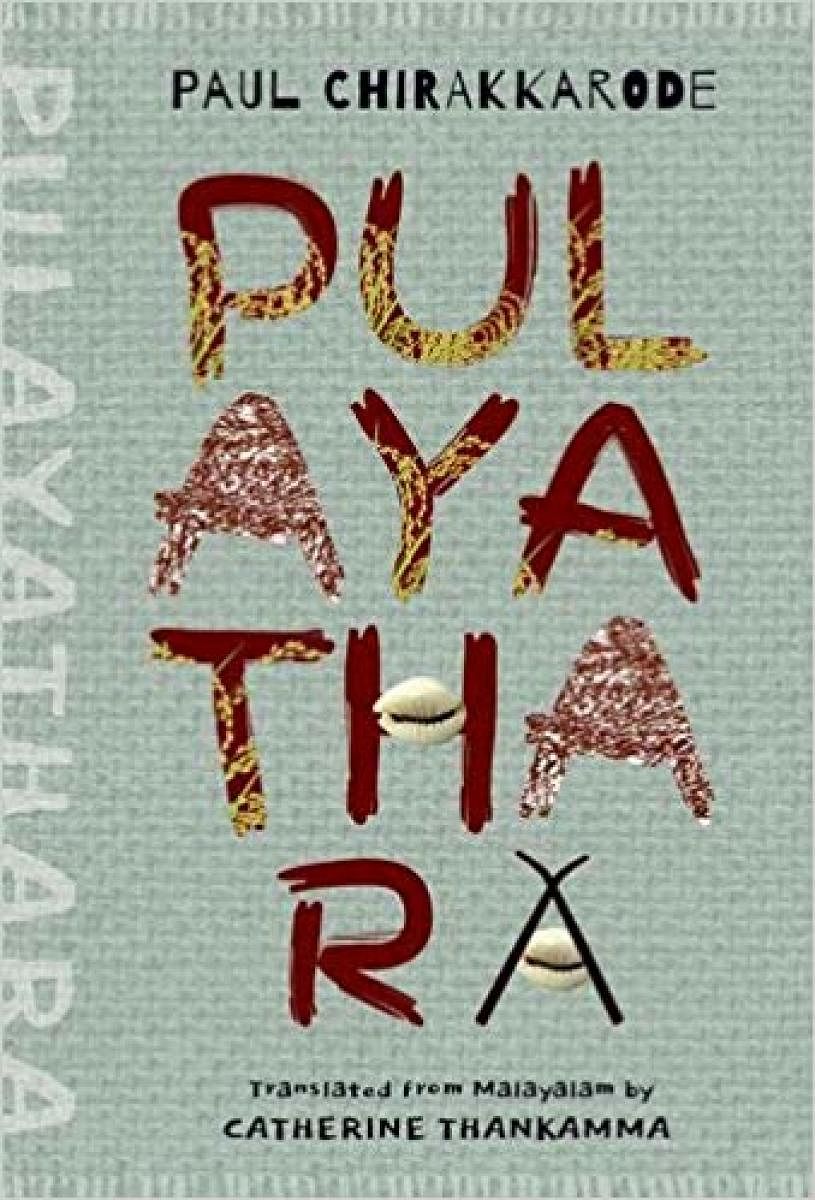

From one moment to the next, Thevan Pulayan loses his livelihood and the shack that he calls home. When one has no home to call one’s own, where is one to go? So begins Paul Chirakkarode’s Pulayathara, translated by Catherine Thangamma, from Malayalam. When a book on a social evil finds relevance 57 years after its first publication, one stops dead in one’s tracks. Like a bulbous, tumorous growth, it demands attention, when one would much rather look away.

This is not the story of one man and the unfairness of the treatment meted out to him. It is the story of a community that has been systematically abused, and discriminated against. Pulayan, the caste that had once owned the land it worked, now stands beggared, maltreated both by the Hindu landlord and the church, denied education and self-respect, or even a bellyful of food that he has helped grow.

Thevan Pulayan and son Kandakoran seek out their only relatives, Pathros Pulayan, Maria and their daughter Anna. But when guests overstay their welcome and food becomes scarce, ill-will and hostility come seeping through. Seeking to escape the crushing effects of a caste system, “that spelt out with brutal clarity, their worthlessness as human beings”, Pathros Pulayan, has converted to Christianity which promises equality among men, an impartial God, an undivided Heaven, not to mention a piece of land to build a shack.

But the caste system is more insidious than he suspects. For in truth, there are only two castes in the world: the haves and the have nots. Whether the haves wear the face of a wealthy Hindu landlord or of a priest or a custodian in the church, the fact remains undisputed that they are different, better, superior to the Parayan and Pulayan, the “new Christians” who convert to their faith. In the church that promises a fair and equal treatment, the place of the Pulayan is in the front, on the floor of the church. He feels privileged to be there, while those who trace their antecedents to St Thomas have a natural right to sit on comfortable benches with backrests, their powdered wives beside them.

The tea stall owner Pillaichan asks point-blank — “They get the poor Parayan and Pulayan to join the church. What for? To exploit and exclude them”. Not that he is beyond taking advantage of poor Kandankoran when the boy comes to him seeking help. But the winds of change are blowing hard.

Although Pulayan and Parayan have been denied education, their minds kept in darkness and centuries of servility have tied their mouth, the gross unfairness of their situation now gathers force like a snowball and there is no stopping it. How will the Pulayan be seated together with the high caste in Heaven when they are so clearly separated in church on earth? Even naïve Kandankoran who converts to marry his love Anna understands that this is not his world, that he can never truly belong.

Towards the end, the first steps towards freeing the Pulayan from his abjectness are being taken. Hope glimmers like a light in the distance. Parts of the book may be autobiographical, for Paul Chirakonde was himself the son of a Dalit preacher. It is hard to imagine what reaction the book must have provoked at the time of its publication but in our supposedly more equal world, it still prods us into stepping back and taking a long, hard look at ourselves, our beliefs and prejudices, and pray to be led from darkness into light. Excellent translation by Catherine Thangamma makes the book eminently readable.