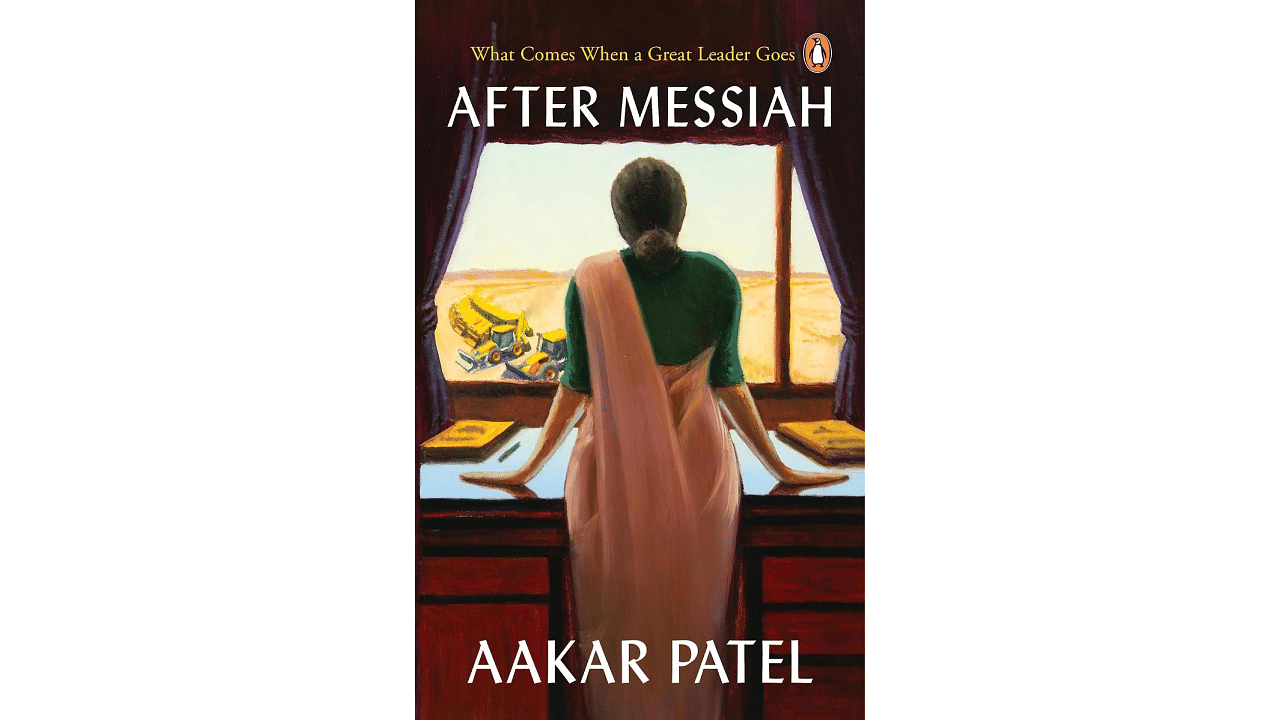

After Messiah.

Credit: Special Arrangement

Aakar Patel’s first attempt at fiction is interesting, to say the least. This political tale begins with the sudden demise of a strongman leader, the Big Man, and the rest of the narrative traces what happens in the vacuum left in his wake.

This vacuum is primarily defined by utter confusion since the departed leader, who had reformed the entire state around his particular genius, held all the reins of the government in his hands, with virtually no one being groomed as his successor. Which, of course, does not deter the top two in the hierarchy from immediately getting into a succession battle; and yes, electoral processes notwithstanding, it is nothing less than a succession battle, with the throne clearly in sight.

In one corner is the departed leader’s second-in-command, a brusque man defined more by his uncouth behaviour and his penchant for intense surveillance of just about anyone and everyone in the political firmament. In the opposite corner is a holy man who leads a state, his robes of the ‘sacred colour’ in no way diluting his keen political ambition.

Just as things seem set for a battle royale, enter the interim leader, the daughter of a now-deceased member of the ruling party. She is able to define ‘interim’ quite clearly, knows her place, and knows better than to nurture any kind of unseemly ambitions. The ideal placeholder, if taken at face value.

Only, the interim leader was once an activist and still appears to hold strong opinions on land grab operations and pliant land acquisition laws. Two seemingly right-thinking people in the PMO are her initial guides but the lady somewhat unexpectedly acquires a mentor in the house manager. After which, things go haywire, with an expected severe pushback from the two rivals for the Main Seat.

This is a nuanced study of power in all its forms, up close and personal. Patel employs a direct style, with no nods to arch innuendoes, and he draws an alarmingly clear picture of a State clasped tight in the fist of an extremely authoritarian but charismatic leader, the one who dies suddenly at the start of the story. The cut and thrust of political manoeuvring, the gaming of systems and processes, the studied normalisation of the merger of state and religious institutions, the pushback from corporate entities, state control tightening like a noose (laws amended, agencies unleashed upon the opposition) around the neck of the country and its citizens, both hapless…it’s all there, sharp and glaringly evident.

The author does not employ any overt irony in the tale despite the subject matter. But it’s not all grim and serious; there are passages which will have the reader chortling or snorting, depending on their political leanings. For instance, when someone from the PMO, wandering about the Rose Gardens in the head of the state’s residence, remarks that there is a variety of roses named Jawahar: strong fragrance, 41 petals, velvety to the touch. In another instance, there is talk of a rival’s weak spot: his seemingly less-than-bright son. Then there is the return of the hitherto sidelined Party Elders. Or when a news channel dutifully runs a news item they have been given, with an announcement that it is ‘exclusive’!

The portrait of the Surveillance Man, who has egregious material on just about everybody, is one calculated to repulse. A tractable legislature, a subservient media, a disempowered populace, and the never-give-in attitude of activists, all seem to be art imitating life. Some amount of the emotional content of the tale is lost to the brisk pace, though. The land grab by the government comes to centre stage at some juncture and then stays there, pushing other matters to one side. At some point, the interim leader says the state exists to serve the people. I defy the reader not to emit a hollow laugh at that point. And yes, this reviewer definitely felt the ending was a damp squib, considering the build-up. One does see the sense in it, but frankly, one would have happily settled for poetic justice of sorts being served to those who deserved it.