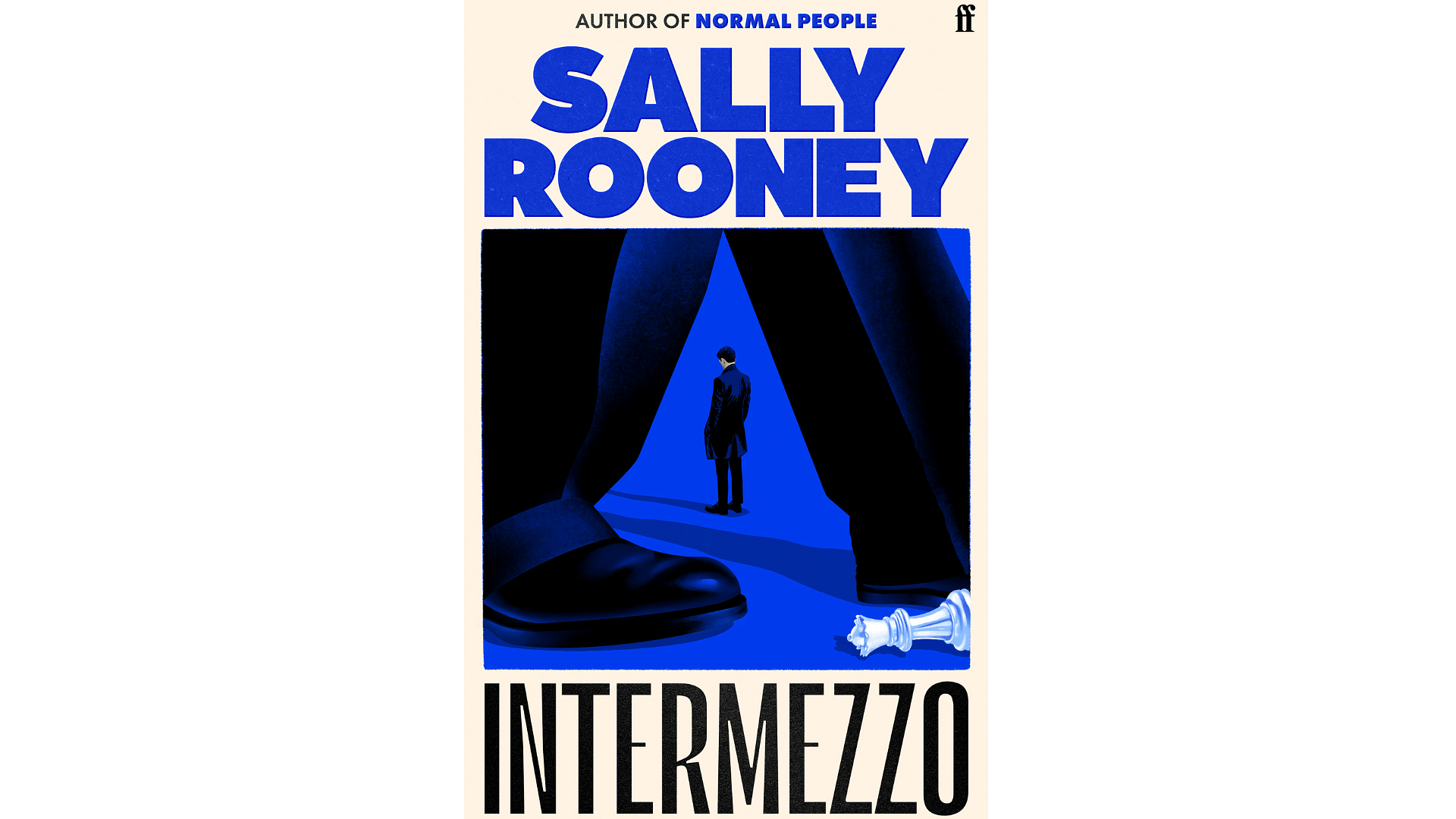

Intermezzo

Credit: Special Arrangement

Bestselling author Sally Rooney has deftly portrayed the loneliness and disillusionment of the post-truth and religious world in her recent release, Intermezzo, by crafting a narrative saturated by her characters’ inescapable regrets. Suffocated by their regrets, the characters are, at any given moment, on the verge of exploding, pulled apart in opposite directions by expectations of conformity and the temptation of their desires. Almost too scared to take their misery seriously and peppering every heavy confession with the usual ‘whatevers’, Rooney’s characters are always at the edge of despair, mechanically following the motions of their drab daily lives.

The problem occurs with her approach to characterisation, which is simple: she takes four characters, gives them four different jobs, and thinks that will automatically translate to four different lenses on life. Except these are not four different people; all the characters walk and talk in the same manner.

Peter, the lawyer, has been struggling after his breakup with his college sweetheart Sylvia, who got into a horrible accident seven years ago, closing off any possibility of sex. But this is not the story of that turbulent time. The novel picks off with Peter dating a decade younger Naomi, who engages in the occasional Onlyfans and lives under the imminent threat of eviction in a flat in Dublin with her friends. Peter, who is still not over Sylvia, has an impossible choice to make: to choose between these two women or better yet, to love them both (a classic Rooney trope).

Then, there is Ivan, the chess player who is Peter’s younger brother. He falls in love with 36-year-old Margaret, an art director from a small town who is separated from her alcoholic husband. The story opens at the funeral of their father, with Ivan and Peter’s already strained relationship stretched thin by grief.

Even an initial look at the synopsis tells us that the problems faced by the characters mirror each other, and there’s no shocker there. All of them do, in fact, give in to their desires. However, the conflicts stifling those desires are left severely underexplored. In the end, Rooney is only fidelitous to the triumph of love in her novel. For instance, how a polyamorous couple navigates through feelings of jealousy or concepts of possession is not even remotely explored. The climax is in the subtext from the beginning. Peter just needs to get rid of his shame and the throuple will fade happily into the sunset.

Ivan, the chess genius, is clearly neurodivergent. His mechanical thought process and his inability to come to terms with the randomness around him all point to him being on the spectrum. But there is this weird dichotomy Rooney has constructed. Ivan’s hyperfocus and mathematical thinking are limited to chess and his inner monologues. When it comes to his love affair with Margaret, he is perfectly capable of the emotional register of a conventional man.

Rooney misses the opportunity to explore the nuances of a new language of love. Love is the ultimate salve in the Rooney universe; Ivan’s earlier alienation, incel ideologies and anti-feminist tendencies melt away at Margaret’s touch. Noami’s financial dependence on Peter and her precarious living situation are just fillers, never seriously approached. Rooney only gives us a slight idea of what intimacy beyond penetrative sex would mean for Sylvia and Peter.

The only serious experimentation in the novel is of style. The sentence structure doesn’t follow your standard subject-object chronology. Using a staccato register, flaunting all rules of punctuation (a full stop where there should have been a comma or an exclamation point), she talks in fragments. She abuses the good old period, but it very quickly becomes part of her narrative.

In every scene, she has her own obsessions to follow, and the omniscient narrator leaves very little undescribed. She describes every microexpression and sensation felt by the body, which creates an intensely vivid narrative. Rooney leaves the reader with a lot of visual cues; the downfall of this is some scenes read more like a screenplay than a novel. What we have then, is a cluttered narrative with sentences that could have been easily omitted out. Despite these moments of fatigue, Rooney lucidly captures the raging loneliness plaguing our daily lives. What is then the recourse when the centre has effectively fallen apart and gone up in flames? Rooney, like Eliot, returns to faith, the Christian tradition of surrender and acceptance as her only hope in this wildly absurd world.

The sex scenes are undoubtedly the high points in the novel. Rooney is still the master of writing good sex. And, love does really transcend all boundaries and precarities of age, class, and gender, but it also transcends nuance in Rooney’s universe. And if we call the novel what it is, i.e., a beautiful exploration of unconventional love, albeit a bit too long and repetitive, Rooney is still the master of love and interpersonal relationships. Beyond that, she seems to have bitten off more than she can chew.