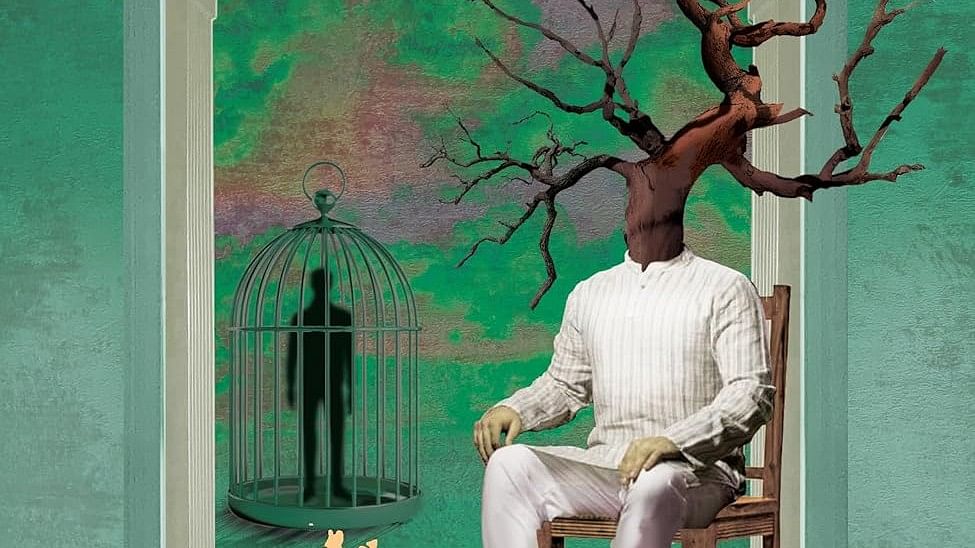

'The Meat Market' book cover

Credit: By Special arrangement

In The Meat Market, a collection of 10 short stories and a novella by the Bangladeshi writer Mashiul Alam and translated from Bengali by Shabnam Nadiya, the grand guignol visions conjured up by the author’s prose are not for the squeamish. And if you’re an animal lover then know that there are scenes of breathtaking cruelty here that many modern writers would think twice about describing even in service of a story.

The uninhibited flights of imagination that Alam takes are shocking but also refreshing in their raw, visceral rage and power. The author doesn’t shy away from shaking his reader to the core and for a large part, he succeeds. Nadiya’s translation ably conveys the very specific sense of place and chaos of post-liberation Bangladesh through passages of text that are as poetic as they are bloody.

These stories are described in the publisher’s blurb as hyperreal and while they do fit that description, more often than not, the underlying conflicts that gird the narratives are very much rooted in the actual world. Alam, a journalist by profession, has a clear understanding of what fuels the human proclivity for violence and the socio-political forces that shape the destinies of nations that are still forming their identities.

The most powerful stories in this collection deal with extreme hunger that drives both humans and animals to commit transgressions that are met with unspeakable violence. From the unnerving cross-species bond that develops between a child and a dog to a cow in desperate need of sustenance, these stories unfold in the most unexpected ways. In the story that gives the book its title, a quest to purchase meat for Eid leads one man to a fateful argument in the market and he addresses the reader who might be shaking his head at the turn the story has taken and the incidents that occur:

“Unthinkable for you. As you use words like unthinkable, unimaginable, impossible, unprecedented, gruesome, you can see for yourselves, day and night, night and day, how many different incidents are taking place all around you. You yourselves are making them happen.”

Bangladesh’s relationship with India, one that is fraught and fraternal on both sides of the divide, is the most obvious theme in the story An Indian Citizen Came To Our Town. Here, in the titular town by the border, an Indian citizen comes to die and it’s the most exciting thing the residents have experienced in years. The story is narrated by a group of youths who are proud to claim their Communist beliefs and thumb their noses at their more devout countrymen, but their hypocrisies are laid bare as their prejudices turn out to be as commonplace as everyone else’s.

While the short stories are brief and intense in their focus, in the novella Pony Masud that closes this collection, Alam takes a more garrulous approach to building a character portrait. The man in question, Masud, has been given the moniker Pony because he rides a Yamaha motorbike while building a reputation as a fearsome gangster and also because two of his grandfathers rode horses in their day. This fact is introduced in a series of overlapping and unreliable histories provided by the residents of Roop Nagar, Masud’s hometown.

Alam is clearly having a lot of fun while writing Pony Masud’s adventures, even giving the young thug an enviable organisational ability: “The marketplace was also famous for assault and murder; before the arrival of Pony Masud when other gangs were active there, there was chaos among the extortionists…Pony Masud arrived and established order in the extortion processes.” While Pony Masud wears its dark humour on its sleeve, it doesn’t quite have the impact of the shorter tales that precede it in the book. The most unforgettable of Alam’s stories here is also probably the least fantastic and where the theme of hunger is front and centre. In Akalu’s Journey To The Land Of Red Earth, a labourer joins the seasonal migration to the “…khiyar country, the region of red earth…” where the rice paddies have ripened.

Akalu is introduced to us as being ravenous and the long journey has only deepened his hunger. He eats a bun but misses his train and encounters a fortune teller. Akalu doesn’t have much money and fearing the fortune teller’s prediction of misfortunes and perils, spends the last of his takas on an amulet. He eventually reaches the khiyar region but there, too, his gnawing hunger is not sated immediately. When he finally does get the opportunity to eat rice, in a few short powerful paragraphs Alam shows us what hunger and extreme poverty do to a man.

You won’t find escapism in these stories, but a brutal, roiling world beneath the veneer of civilisation. And that’s fine — sometimes a rude awakening is needed to stop us from getting too complacent about our lives.