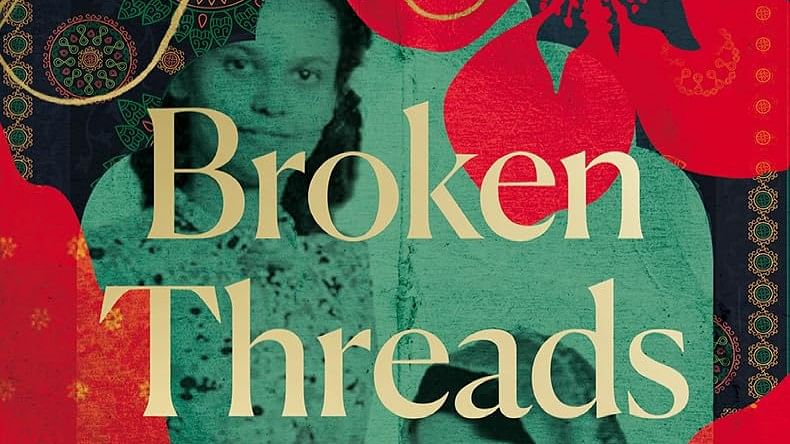

Credit: By Special Arrangement

Mishal Husain grew up in a household with a little video library and where TV was minimal. There was great excitement when the first Betamax VCRs appeared and she reveals in an interview, “I was particularly tuned in to my parents’ conversations about the news and its implications: I remember them talking about the famine in Cambodia, and speaking in hushed, shocked tones about the assassination of Egypt’s Anwar Sadat and then of Indira Gandhi in 1984.” Perhaps this experience has seeped into the writing of her latest ancestral history, Broken Threads, a journalist’s account of pre and post-partition India.

Mishal remembers reading Christabel Bielenberg’s The Past Is Myself as a teenager which is an account of the Second World War written by an English woman, Christabel, married to a German. Mishal tells me about the book in an interview: “I think it was the first time I really felt history was immediate, it was what people had lived through.”

Broken Threads is an attempt to understand how the huge 20th-century shift from the age of the Empire to the age of the nation-state affected society and individuals. Right from the outset, the book is different in its approach to history: It moves away from the ‘general’ to the ‘particular’.

It is so seldom an occurrence for a memoir to rob itself of the ‘I’. I expected the story to inevitably lead me to her, rather she came as little glimpses, as a propeller, and even as a compiler of disparate threads of her ancestral history. For those of us who find the numerous large biographies daunting, this unassuming yet impressively comprehensive volume offers a pleasant stroll over level ground.

Her paternal grandfather Syed Shahid Hamid was the first Master General of Ordnance (MGO) of the Pakistan Army. He kept a journal which was later retrieved and posthumously published as a memoir, Disastrous Twilight: A Personal Record of the Partition of India 1946-1947, an eyewitness account of being on the staff of the last British Commander in Chief of the Indian Army, Field Marshal Sir Claude Auchinleck. Broken Threads borrows a great deal from the record.

When I asked Mishal how this book was conceived, she shared, “I felt the tale of how the Empire in India came to an end deserves to be much better known: how little time and government attention was given to it, despite millions of lives being at stake. Britain had governed, and its many imperial subjects deserved deeper focus.”

Broken Threads is indeed a work of extensive research. As a BBC correspondent, Mishal has visited India several times. She recalls visiting Dandi, where the Salt March led by Mahatma Gandhi reached its climax: “At the time I didn’t know that one of my great-grandfathers had been employed in the department which collected that very tax!”

Husain comes from a generation of kin who diligently recorded experience. Their personal stories of love, longing and career seamlessly intersperse with the geographical history of two nations on the cusp of formation. Their real-life narratives help bridge historical gaps. What starts as a simple exploration of her two grandmothers’ lives, one Muslim (Tahirah) and one Anglo-Indian Christian (Mary), and through them an exploration of social mobility, educational opportunities, and the transformative power of change for women in early 20th-century India, quickly unfurls into a broader narrative of the lives of her grandfathers Shahid and Mumtaz, whose writings, published and unpublished, provide a textured backdrop to the family’s history. Shahid’s partition diary and Mumtaz’s unfinished memoir brought to life their roles in the British Indian Army, medicine, and civil service.

Tahirah and Mary, too, take centre stage. The treasure trove of tapes recorded by Tahirah recounts her experiences during the Partition of India in 1947 as she says, “Bricks and mortar don’t matter, people do.” This was quite in contrast with Shahid’s complacency which came from a certain idea of “sons of the soil” in Pakistan. Her grandparents serve to fill gaps in our understanding of India’s past not just through huge globs of facts, armies or historical figures, but actual people, who were as much a part of the Independence movement as were Gandhi or Nehru. Figures like Mohammed Ali Jinnah are also seen in a personal light, which is quite refreshing.

The book introduces the idea of alternate realities, both personal and national. She says: “I do have a deep personal sadness at the lost links and lost access to shared heritage. My grandparents had very little opportunity to cross the border from 1947 to the end of their days. Mary did it perhaps three times, to see her mother, near Vishakapatnam. Tahirah did it too, in the 1950s and early 1960s, to see her parents in Aligarh. But for the most part, links were severed.”