In Praise Of Laziness

Credit: Special Arrangement

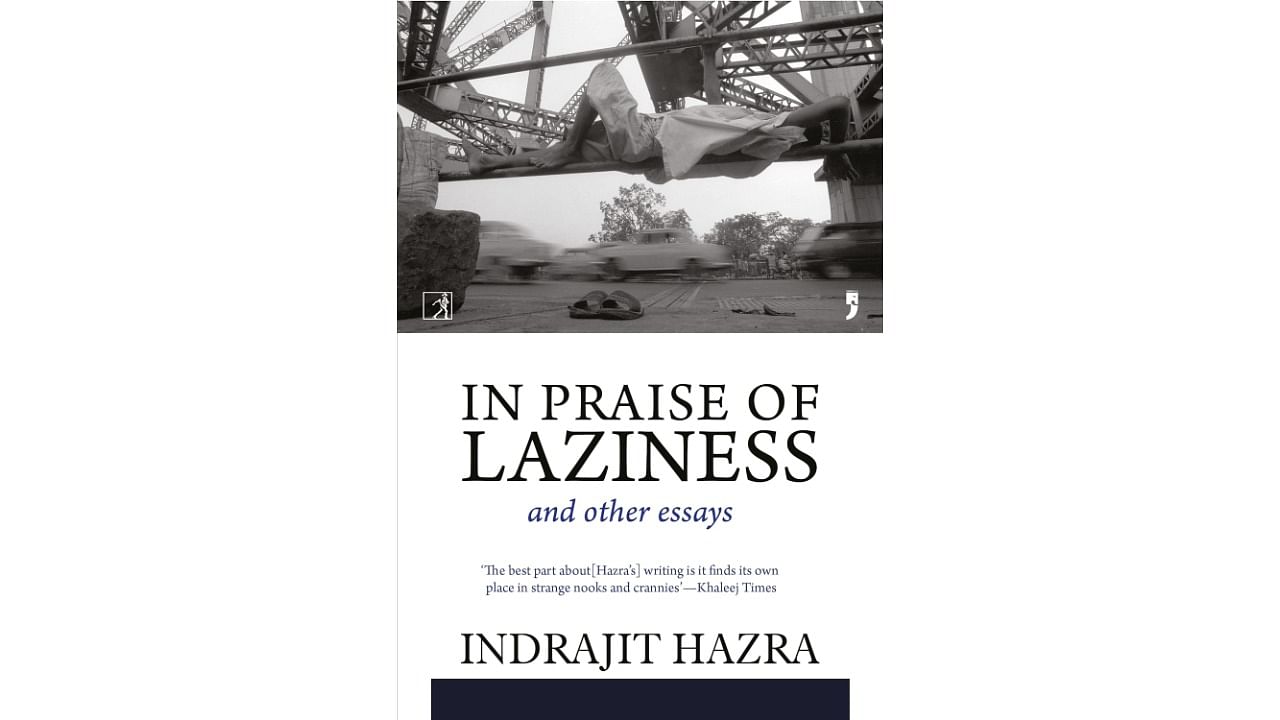

Every once in a while, you pick up a book for its eccentric title (or cover, let’s be honest); and as soon as you start reading it, a wave of equal parts glee (of having discovered it) and guilt (of not having done it sooner) engulfs you. Indrajit Hazra’s In Praise of Laziness and Other Essays (2023) falls in this category.

In the essays in question, the writer-journalist wanders through the disorderly maze of life, art and our (his) interaction with both. The result, as he calls it, is “irrelevant, irrelevant”. He calls this collection random and perhaps in their textbook sense, they might be; but with each passing topic, we come closer to the marvels of Hazra’s disquiet, yet strangely placid mind.

His breadth as a writer is exceptional. If there is humour and unmatched wit in the title essay which makes the case for idleness that takes effort and great perseverance, then Hazra takes a 180-degree turn in Becoming Adult, where he speculates the possible adulthood of children who never get a chance to grow old — by building a case for two fictional characters that have been immortalised as ‘boys’ in literary eternity: Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn (1876) and Sukumar Ray’s Dashu (1916). His range is evident as he goes from “Laziness could have stopped the world from hurting itself” in the former essay to “All old people have been young. But not all young people have been old. Or need be” in the latter.

Most of the writing in this book is “spanking new”. In a front-row ticket to his musings, we navigate from one corner of his intellect to another. As Hazra enters a sentence with one thought and ends it with an entirely different one, we follow him as he punts the human need for belongingness inside and outside the boundaries of one’s nation and the ever-expanding social bandwidth with social media on the rise, in A Man of the Great Indoors: “If the glue of language doesn’t quite fit… then a buffet menu of culture has to do the trick.” On the other end of the shore, in The Purge a.k.a. the Dry Day, he questions the spiteful virtues of alcoholism — a debate between Gandhian versus Tolstoian schools of thought, where one is hell-bent on abstinence and the other is more lenient as long as one’s conscience is retained, even if under alcohol’s influence.

Hazra plays with words, much like a child who plays with food — an act many adults may find disrespectful but in reality, is the child’s way of exploring the world and finding his/her own way. He fancies the “seasonal luxury” of electric blankets; mishears “misogynist” as “miso soup”; prefers “Francophonic” to “French” and “Felumenon” to “Feluda phenomenon”; construes the moral dilemma of public deaths as a private versus social event; loves a sport — football — that many Indians do not relate with; and dissociates with a sport — cooking — that many do. In a final stunt, his comic timing hits the spot as he neatly slips in a piece of fiction between the essays — a colonial fantasy/sci-fi, where “white humans” are the “aliens”, the “Outworlders”.

Singularity has no place in Hazra’s world. He observes and engages with the world with all his senses and his writing reinstates one’s faith in the multi-dimensional, multi-directional, cultural, political and economic realities of our times. His writing is lucid, compelling and undeniably visual. No matter the length of his book, Indrajit Hazra’s creative footprint is long-lasting.

As much as I have enjoyed reading and rereading these essays, I say, with great envy, that it is indeed possible to enjoy them even more — by knowing his references to the finest, tiniest, last bit. That said, Hazra has an extraordinary talent to show his readers another way of looking at something they may have known all their lives. A sincere writer remodels the world for his readers. A diligent reader, on the other hand, takes away a list of things to read, watch and listen to, from the writer. In Praise of Laziness makes a golden space for both to co-exist.