In 1997, Charles Frazier’s first novel Cold Mountain, a doomed romance between a Confederate deserter and a preacher’s daughter set during the American Civil War, was published. It came out after Anthony Minghella’s film adaptation of Michael Ondaatje’s The English Patient (1996) had been released and before James Cameron’s Titanic (1997) took over the world. The public was primed to lap up fiction centred on star-crossed lovers and Cold Mountain was a bestseller. The critics loved it too, praising the novel for its lyrical prose and Odyssey-like plot and Frazier also won the National Book Award for fiction. Minghella directed the film version some years later.

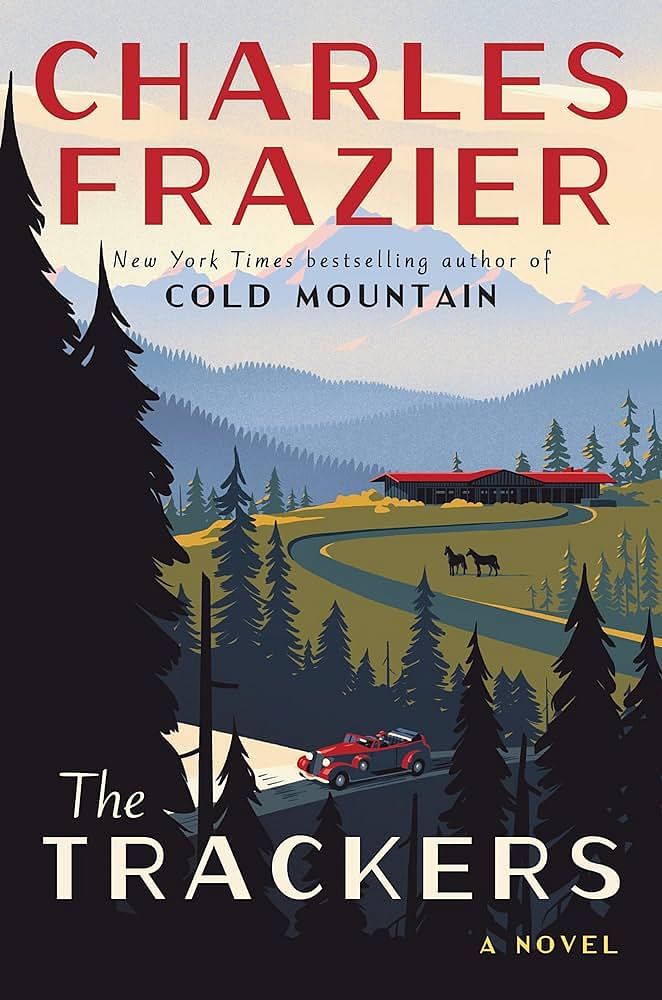

Since then Frazier has written four more novels, with the latest, The Trackers, published this year. This new work tries its best to recapture that magic from three decades ago, but what we have is a rather half-hearted attempt at a Depression-era odyssey through America with characters that make illogical, puzzling decisions. The main character here is an artist, Val Welch, who’s been given the task of painting a mural in the post office of a town in Wyoming, part of the New Deal projects that President Franklin D Roosevelt had implemented to restart the country’s economy after the 1929 Wall Street crash.

We join Welch as he travels to the town of Dawes and get some tepid descriptions of landscapes, the equivalent of a PowerPoint presentation on Roosevelt’s aims and ambitions with these New Deal infrastructure projects, and technical details of painting murals with egg tempera. I wasn’t sure when I read the early pages, where exactly this novel was going.

During his sojourn in Dawes, Welch is lodged in the guest cabin on the ranch belonging to wealthy, Ivy-league-educated cattle rancher John Long. Eve, Long’s wife, comes from a completely different background than her husband. She was born into poverty and lived an itinerant life before becoming a singer with a touring cowboy band. It was during one of their performances that she caught Long’s eye.

Long considers himself a great patron of the arts and has a collection of fine art gathered at the end of the First World War in Paris. Among them is a sketch by Renoir — it is this small treasure that Eve runs off with, one day. For some reason incomprehensible to the reader, Long asks Welch to track her down and find out where and why she’s run off to, and get her back to Dawes.

It was impossible, as I read The Trackers, to shake off the fact that there seemed to be a good novel hidden somewhere here, but without any heat, the book was falling completely flat. When a late-stage romance is introduced between two characters who’d barely shown any interest in the pages prior, it feels too little too late.

As to the mystery of Eve’s run-off, it isn’t that hard to guess. When it’s explained on the page in prose so anodyne and lifeless you question what happened to the Frazier who wrote Cold Mountain. The author himself seems to (sub)consciously convey the impossibility of emulating his previous literary accomplishments when Welch reflects at one point in the story while contemplating his almost completed mural:

“With creative work, surely doubt and disappointment are inevitable. If you have ambitions, the things you create will always fall short of what you intended.”

The Trackers is also the title of the mural that Welch creates in the Dawes post office. For any Parks and Recreation fan, the details that Frazier lets slip of the artwork might have the unfortunate effect of recalling the murals that appear in that show. Sure, The Trackers mural is depiction of Wyoming’s heroic people and their rich fauna and flora and not the satirical takes on US history that are strewn around Pawnee, but like so much in the novel, its nebulous descriptions and lack of a concrete theme that Welch himself confesses to on the page makes you wonder if there might have been a better book in here somewhere if Frazier and his hero had taken just a little more interest in their respective projects.