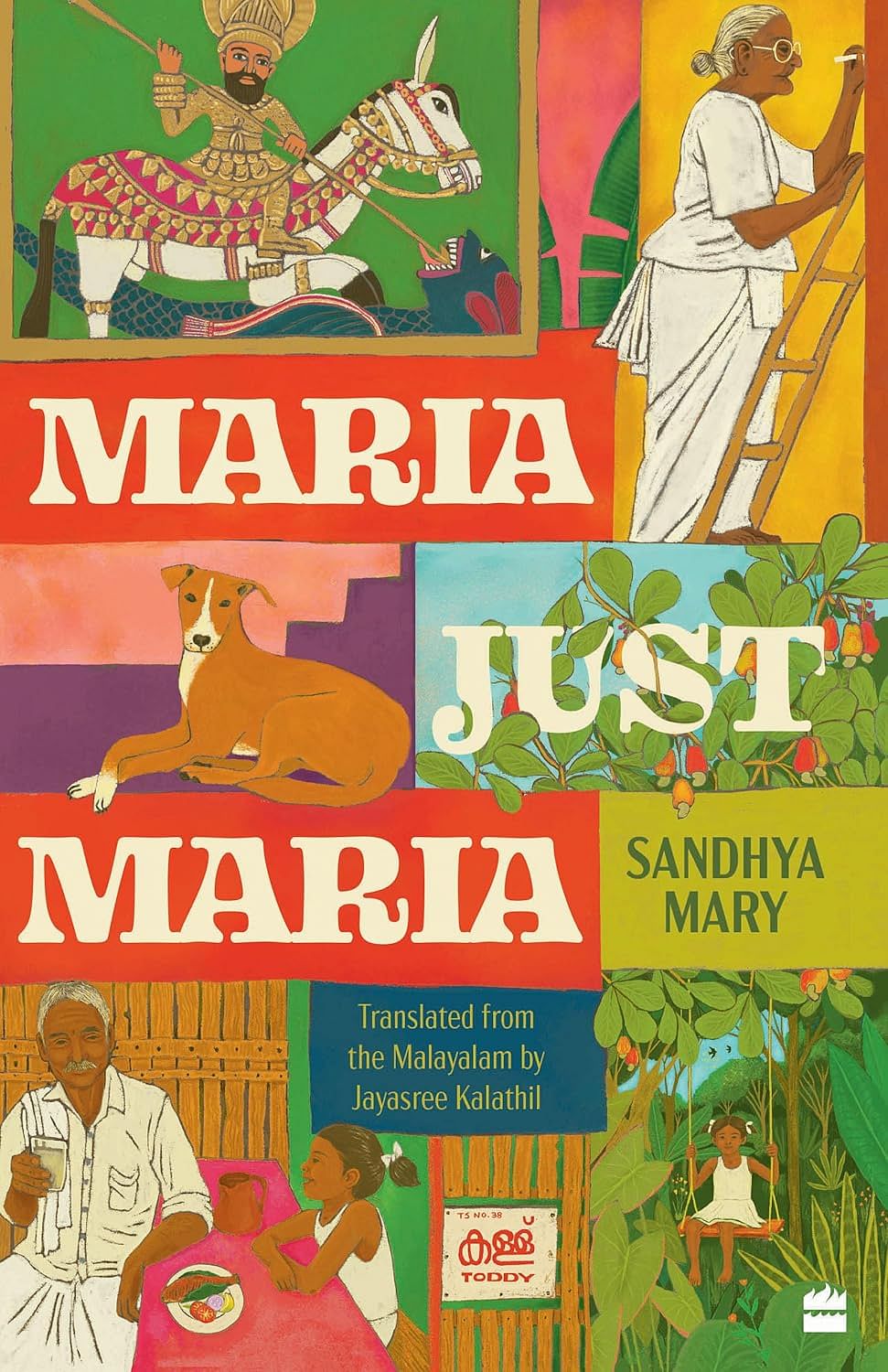

Maria Just Maria

A book that opens onto a dreamscape and extends the idiom of every woman’s dreamscape is a book all of us have dreamt of. More a revelation than a book, Maria Just Maria, written in Malayalam by Sandhya Mary, is not just Maria’s tale alone; but the story of all thinking women, of a time, of time beyond history, of Syrian Christian households, of Kerala’s society, and by extension, a story of how women flourish or flounder in our world. Much life has been breathed into the work by translator Jayasree Kalathil.

The author writes with great expertise and sensitivity about a woman’s world. The observations and nuances within the text are uniquely feminine: no artifice or numbers, there is no needless cerebration. This is unabashedly about the liminal, about a woman’s vantage and a sensory fabrication of a world she knows. Some men play a pivotal role in this world for an ideal world is gender-neutral, and offers equal space to all. These men love without limit.

Maria’s story is difficult to extract from her family’s surrounding tissue and its lore. The basics are given upfront. Maria is not alright in the head. Maria is so not alright in the head, she is in a mental institution among kind nurses, fading thoughts and accomplished fellow patients. Of all people, her maternal grandfather Geeverghese Appachan is blamed for her situation, for was it not he who as a wayward drunkard brought her up till she was six or seven? Geeverghese is named after St George aka Geevarghese Sahada but is ironically most irreligious, hated by his father and wife for his un-Christian ways. His love, for Maria, has been the sun.

Within the story are Maria’s pet, the colourblind Chandipatti and a talking parrot, Ammini. Generations of the family are sketched, not with the family tree kind of intent, but as a repository of stories. There are gorgeously beautiful women and their negligent husbands. There are impoverished grandaunts who have Alzheimer’s to save them from a life of guilt. There is the love of Geeverghese’s life, a drinking partner Kali, who runs away with a wandering merchant almost the same time the former discovers he would leave his wife to marry her.

The church, its priests, and saints loom throughout the narrative. The characters too are arrayed in two shades: the pious and the ungodly. The latter demographic seems to have more loved characters: pitting the believers against the iconoclasts, the followers versus those who would be independent or lead. The church also provides names for all, godly or otherwise.

While this is a beautiful coming-of-age story too with mentions of Chitrahaar, Parry’s sweets, Binaca toothpaste with its animal collectables and a Boris Becker fixation, the Emergency, its fallout and Indira Gandhi hold a place in the minds of those in rural Kerala too. “If a man has a good job, he is considered accomplished, even if he has no children. But for a woman to be considered accomplished, she just has to produce some children. She can go to Pluto and back, and still, you won’t acknowledge her accomplishment unless she has popped out a few children. Truly, Ammachi, I don’t understand your world or its standards!” At 18, Maria runs away from home. She turns communist like her aunt, even living in a commune with Aravind, Hari and the others. She grows to great intellectual heights, forever a stranger among her people, her thoughts unacceptable to her family.

The author skillfully rebuilds the lost world of childhood and mourns women like Maria who do not emerge undamaged. “As she says this, Maria knows that she will never write such a book. Because, according to Maria, writing books is boring. But Maria will write a book, much later, and she will write it when she is in a place she would never have dreamt of. Poor Maria.”