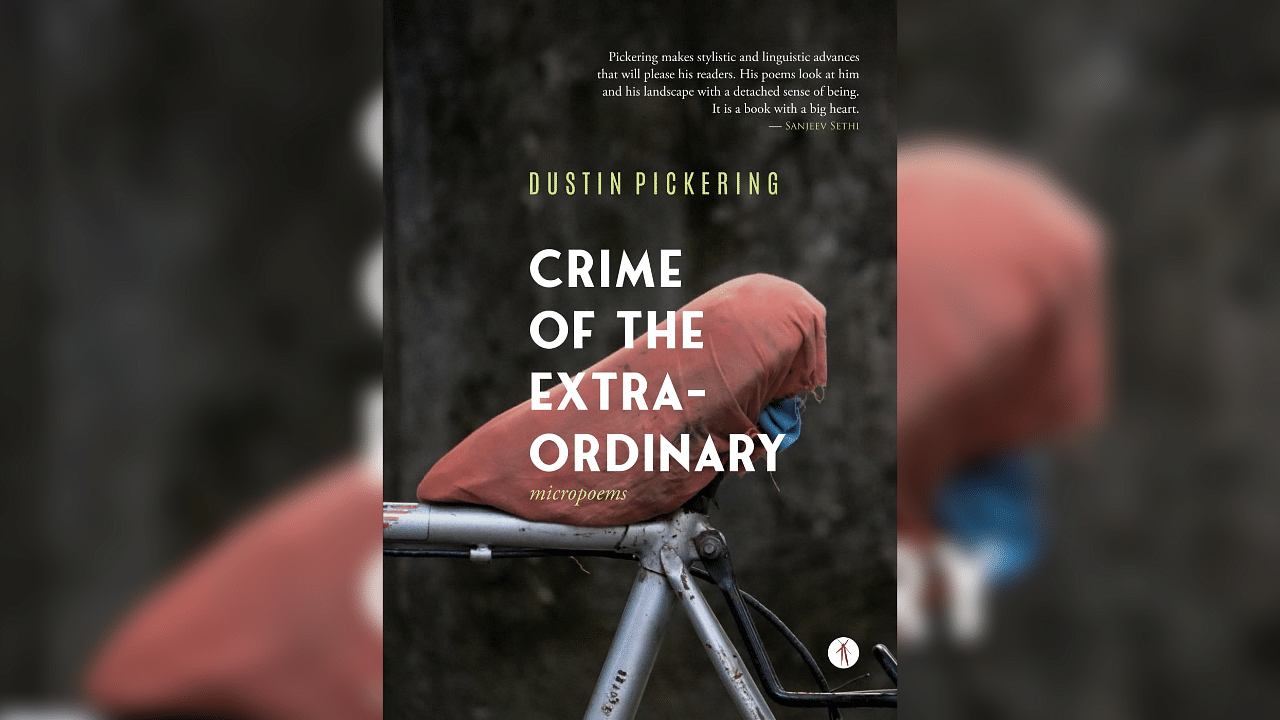

Crime of the Extraordinary

Poems come in all sizes and shapes. We have the epics; the Mahabharata, about 200,000 lines long, is the longest in the world. The Guinness World Records recognises a Kirghiz folk epic of 500,000 lines as the lengthiest poem.

Poems of any length are capable of conveying sublime meaning with grace and beauty. Take micropoems. As the name suggests, micropoems are tiny verses. A popular micropoem is American poet Strickland Gillilan’s ‘Lines on the Antiquity of Microbes’, or, as it is popularly known, ‘Fleas’. This is the poem: “Adam/Had ‘em.”

This month, we are reviewing American poet Dustin Pickering’s 14th book of verse. Dustin Pickering is the founder of Transcendent Zero Press and the founding editor of Harbinger Asylum. He has published several poetry collections, including Salt and Sorrow, Knows No End, and A Matter of Degrees.

Published by Hawakal Publishers, the poet’s latest book is a collection of 69 micropoems and is titled Crime of the Extraordinary. Poetry, by its very nature, uses scant words. A micropoem even more so. The poet works within strict confines to write about the condition of human existence, love, morality, and existential questions. In these narrowest of spaces, he creates memorable moments.

Sample this poem: “Ideologues: They shout from snows/ to pollute rivers already tacked with woe, /a hassle to speak least of these beasts. My home is by the stream, a threadbare insolence, /but I do not seek the riot of my bones. Not like their own.” Polluted rivers, threadbare insolence, and they exist, uneasily, side-by-side. In speaking of the home, the poet seems to challenge the so-called ideologues to engage in true activism.

Dustin Pickering’s poetry carries striking imagery, with comparisons and metaphors effectively conveying a range of ideas. In ‘Pauper’, where he describes himself as “the poorest writer with fewest words,” he says, “I write though trees are screaming loudly in my ear.”

In ‘Origins’, the poet contemplates the eternal question of which came first, the chicken or the egg, ending with the line, “The same material composes both.” I discern not only a sense of stoicism but also a touch of humour in this last sentence. It is as if the poet asks us what the fuss is all about.

In ‘Koh-i-noor’, the poet speaks of the renowned diamond, saying, “The Queen poses marvellously with the Koh-i-noor crown. How do beautiful jewels cross so soundly the land? Encased in the rapturous tower,/ the diamond now smiles like a religion at its victims. Many do not know whether she is real: Queen, or costume? Perhaps both.”

Two ideas stand out for me in this one. I like the contemplative question of beautiful jewels crossing the land so soundly, so safely, so entitledly. I also enjoyed the reference to religion in the diamond’s smile. Is it as mesmerising, as misleading, as dazzling? Does it offer hope? Tying up these questions to a stolen diamond speaks volumes about the poet’s art.

In her introduction to the book, poet Claudine Nash says, “To engage a reader through micropoetry, the poet must wrestle with the art of reduction until certain that only the words carrying their own weight remain(…).”

There are numerous instances through the collection where the weight of the words stays in the mind. In ‘Book’, Dustin Pickering says, “I open the pages, dog-eared by time. Doggerel bites the angel in me. I feel guilt and shame at being naked/ before the muse with such tepid clauses!”

I was reminded of the many, many times when I have read a writer’s work and admired and envied their craft. It has often made me wonder about my writing and whether I should write.

The angel appears in many poems, and I wonder who it is. Is it a side of the poet? A desire for something different? An exalted being that the poet aspires to? This is one of the many questions that the work left me with. Indeed, the beauty of these micropoems is that they leave so much room, quite literally, for wonder and contemplation. In Dustin Pickering’s Crime of the Extraordinary, I agree and aver that “I will take the answers as they come.”(from the poem ‘Language’)

World in Verse is a monthly column on the best of new (and old) poetry. The writer is a poet, teacher, voice actor and speaker. She has published two collections of poetry. Send your thoughts to her at bookofpoetry@gmail.com