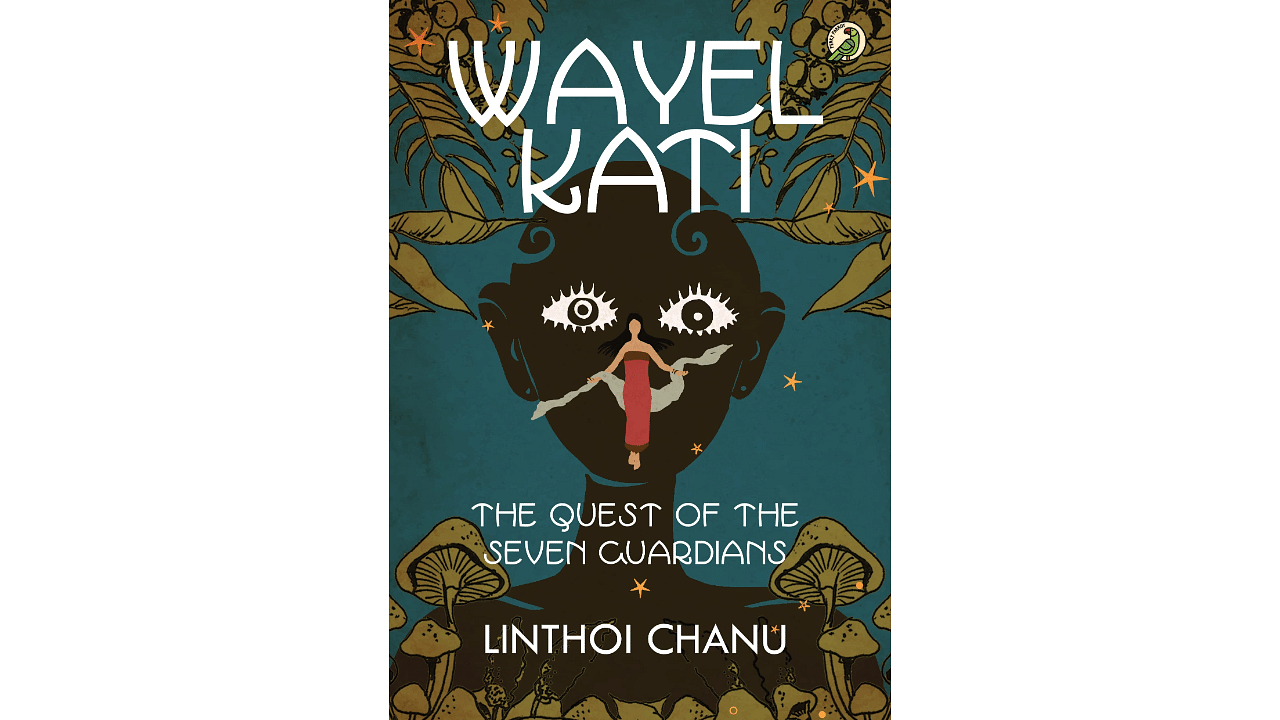

Wayel Kati.

First the good news. The story of the Divine Scissors of Justice, Wayel Kati, is a composite of various folk tales from Manipur that combines all the hero/villain/monsters/protectors/desecrators tropes and produces a very interesting tale.

The list of protagonists is headed by Atingkok, the Father God in the form of an aged hermit holding a long staff, with his silver hair tied into a bun, a drooping moustache, and his slender body covered in a star-spangled robe. He sends a handpicked set of seven youngsters (some of them mere boys and girls) to seek and find the lost divine scissors of justice that guards the realm.

Leading the seven is the strange nine-year-old boy Laiba, he of the very pale skin and mismatched eyes, who turns out to be the head priest in the kingdom of another of the guardians, Iwanthanba, the Meidingu (king) of Kanglei. There is Sana, a nondescript girl who can see the Helloi, evil creatures invisible to other humans, who reveals some stunning powers invested in her as the tale winds to its conclusion. There is Prince Lungchum, the direct descendant of the Serpent King. There is handsome Gothang, son of the Sky Queen. There is the lissome Ningrei who can communicate with the Enchanted Stones. There is Leisatao, the archer, and then, there's a bonus, Pamba Keiremba, who we first meet as a vicious attacker.

As for the antagonists, it's a fascinating pantheon of creatures good and bad. These include the Khutsangbi monsters, dragon-headed giant serpents, the tiger-headed beast Keioba, the utterly charming twin feline beasts who become Gothang's protectors, the Lanmei Thanbi, floating fire spirits of the forest, Kulsamnu, the Guardian of the Door of Death, Gulheupi, the monster python, the Keioibi Pat, the lake where any human who drank of its waters turned into a tiger, Tin-ngam and Lai-ngam, the indestructible giants.

Apart from the good versus evil confrontation, various other strands are woven into this morality tale: two young men searching desperately for their mothers, a newly crowned king who labours under feelings of inadequacy, areas of the province embittered at how they are being neglected by the Central Province, and the inherent message of the Divine Scissors: that people should be blessed with enough but not too much because human greed invariably leads to chaos.

Eye-catching illustrations

The author Linthoi Chanu deserves the highest praise for collecting local oral legends and setting them down in a manner that is relatable to the rest of India and the world. The jacket illustration by Misha Oberoi is a gorgeous eye-catcher, and the illustrations inside the book, done by Yaiphahenba Laisham, are even more gorgeous, inviting the reader to stop and study them in detail, before moving on with the story. The book ought to do well if adapted to an animated film for children and adults alike.

The bad news is the complete absence of a blue pencil. Little or no editing has been done and as a result, the reader struggles with awkward language and even more awkward descriptions, to get to the heart of the tale. To begin with, the pivotal peg of the story, the lost scissors, is written in the singular — scissor — all through, despite the fact that in modern English, the word 'scissors' has no singular form. Dreams are described as 'displeasures'; music 'tickles' at the skin of listeners; disappearances 'ache' people; women run fast but in an enjoyable manner; people look 'admirably' at other people; people 'arrange wedlock' for their children; ears go up like an 'alerted dog', and much more. Editing regional literature comes with its challenges but the total lack of it works to the detriment of the story being told.

However, harking back to the fascinating tale of the Wayel Kati, the major takeaway is how we know next to nothing about the stories that make up the cultural heartbeat of Manipur and its surrounding states. For that alone, we need to convey gratitude to Linthoi Chanu.