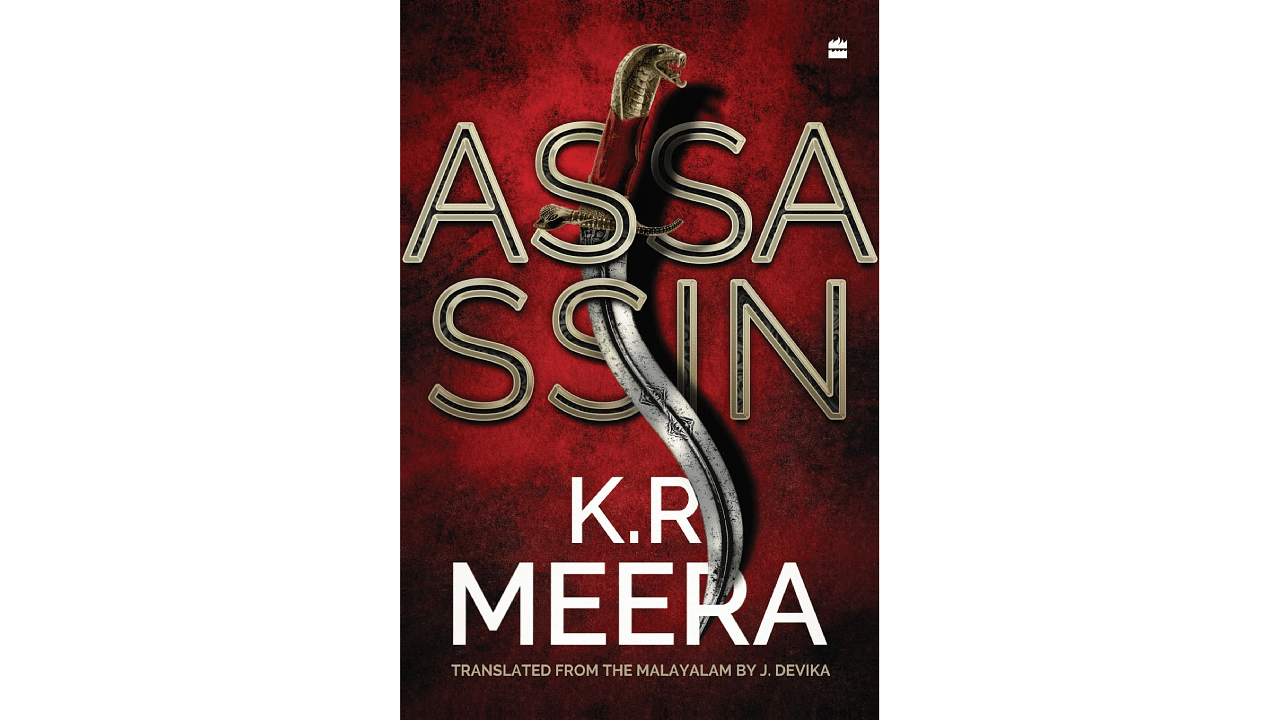

Assassin.

Credit: Special Arrangement

There comes a time in the life of an author when she must simply write her magnum opus. This lifework holds all the shards of her convictions, learning, nightmares and, yes, verbiage. While such an enterprise isn’t always pretty, it’s always the essence of a writer’s true self. Assassin, the translation from Malayalam of Ghathakan by K R Meera, is a milestone offering. Though the “assassin” here is not your garden-variety attacker but a terminator of someone important.

In the eye of the hurricane is Satyapriya, an HR manager in her 40s, who dodges three bullets fired by an unknown assailant in Bengaluru. First, she assumes it is a mistaken identity, but another attempt on her life points to something sinister. On her visit home, her dour bedridden father gathers the strength to warn her she is in real danger before, in true filmy style, he drops dead. Now she must turn detective. Being a fierce, thinking woman, she records each flicker of emotion she goes through. “It is like being thrown into a fire pit. When the fire spreads inside and outside, the body takes leave of the soul, intelligence flees the brain, and the beating quits the heart. We do not exist in these moments. Nothing remains other than the blinding fumes that pierce your eyes and tear them out. You feel nothing but the unbearable agony from the sting of poisonous wasps or the unendurable suffocation from your head being forced into a bucket of water and held down there.” Aided by Inspector Anurup Shetty, who is part formidable and part utterly sweet, she chases each clue.

Satyapriya has the ability to completely mesmerise the men who come into her orbit. It is no surprise the gruff inspector is afflicted, declaring both his interest and love. From her past are the besotted: Sriram, Abhilash, Samir Sayyid, Prabhudev Maheshwari and Swami Mahipal Shah Baba, and oddly enough, her list of those who want her dead tallies exactly with this except that Abhilash is deceased by now and a hired goon named Satyaprakash takes his place. Hers is an impossibly impressive array of powerful men. Samir is a Maoist. Prabhudev belongs to a corporate cartel. Swami is a modern-day guru. The reader gears up for the typical show-and-tell of love stories gone murderous, but the canvas stretches larger. A foetus in formalin among her father’s things reveals the once rich-and-famous producer-director of films hides a past that’s murkiest.

A whodunnit despite intense internal dialogue and scrutiny, in style and in content, this is closest to phantasmagoria. The encyclopaedic snapshots don’t flinch in their stark objectivity even as the prose is impassioned and hyperbolic, and mashes metaphors.

Tough to twirl an ensemble cast of over 30 characters into a reasonable storyline, so full marks. Also woven in are illegitimate children, murderous attacks, paedophilia, organs for sale, Sivapriya’s death by accident, domestic violence, adultery, crushing poverty, predatory men and deep vengeance. The hunt for the killer turns into a sordid foray into her own past and that of her family. The most powerful character is the doughty and unflappable mother, Vasantha.

A lot of the author’s focus is on money and on establishing the horrors of demonetisation through multitiered equivalences. “That is the problem with memories. They are not like currency notes. No matter how much you ban them, they will still return. You will struggle, not knowing what to do with them. The only relief is that there is no law against keeping them. No limits on numbers of value. No fine to pay for excess stock.”

It is a delight to find embedded in the text a scattered monograph on demonetisation. For, the personal is overridden by the political. “You’d be allowed only to spend money printed on yourself, printed by yourself! Would there be tax evasion? No! What about black money or corruption? None at all! But then, there is one thing — it would be difficult to demonetise. To ban someone’s notes, that very person would have to be banned first!”

In the hands of a lesser author, the thriller element of the plotline may have been lost in the labyrinths of descriptions and studious digressions. Here, the reader is escorted through these with a deft hand. Ultimately, the author exposes the greed and lust that instigate killers who live and thrive among us. In essence, this book excavates the consciousness of a community, its laws, its patriarchy and faultlines. And its takeaway is the inevitability of death and the immortality of some loves.