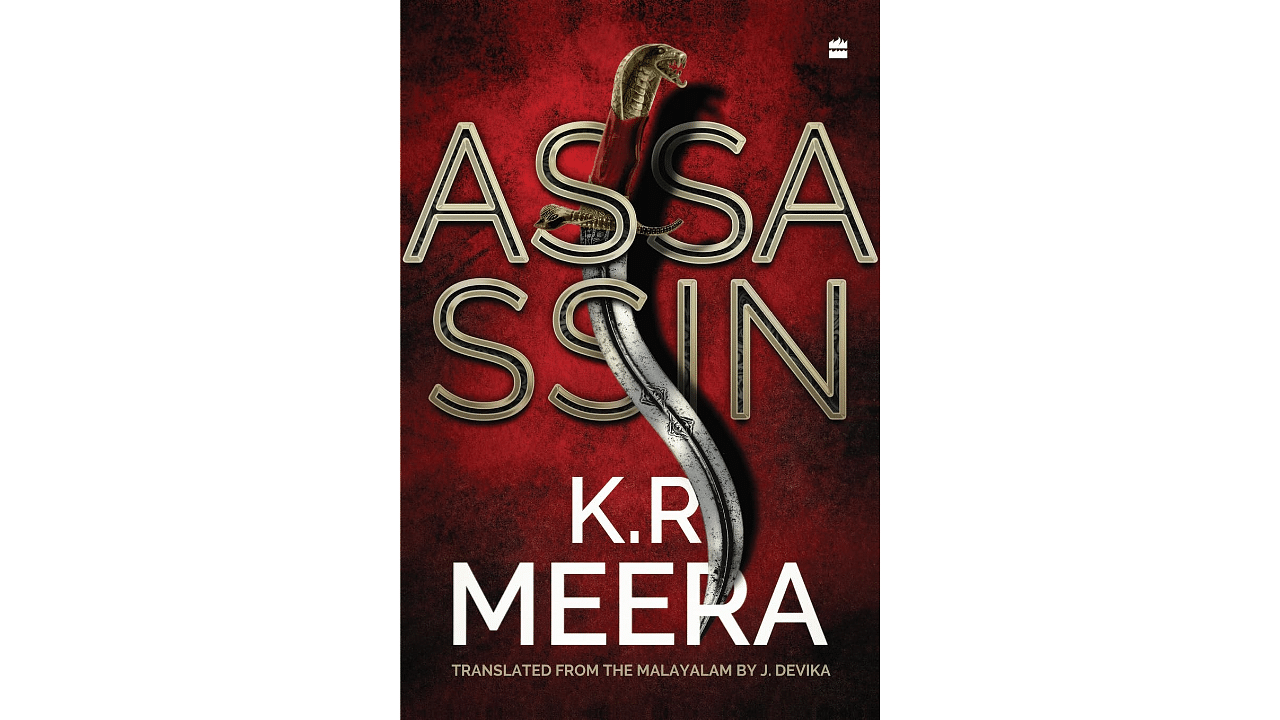

Assassin

Like every year, this year’s Kerala Literature Festival also witnessed long queues of fans waiting for their favourite authors to sign their copies. Among the battery of authors, the queue was longest for the homegrown icon, the literary sensation K R Meera.

The writer, who signed copies for more than 90 minutes, is perhaps more widely known than Indian writers writing in English. While her translators must be accorded due credit, it is her remarkable selection of the subject matter, wordplay in language, and capacity to create urgency drivers that make her works stand out. Her latest, finely translated from Malayalam by the celebrated feminist J Devika, Assassin, is a case in point. In a conversation with DHoS, she talks exclusively about the book and more. Excerpts

As you centralise the feminine experience in your work, I was wondering if you write to verbalise what women bound by the strictures of patriarchy cannot afford to. Is it an attempt to emancipate them?

Unless you document what you’re going through or what you witness around you, no emancipation is possible. That has always been my endeavour: to represent lived experiences. For example, with Assassin, I attempted to capture the lives of the women of our generation. It’s a quest to demonstrate how patriarchy has actually shaped us — our views and lives, etc. And the way the idea of power that lies within the familial sphere and outside our homes has transformed. The old has been dismantled and destroyed; our lives are being reconstructed in a way because of this neo-patriarchy.

Tell us about the distinct style you adopted in Assassin. While your previous works employ symbolism, its use in Assassin is charming. Particularly, the extended metaphor of Gandhi...

My style has been consistent: I’ve always written from my heart. So, truly, I wasn’t trying to do anything beyond prying open patriarchal figures. Anything related to patriarchy must have its own fatherly figure, so I choose to employ Gandhi. But if you observe closely, such figures have undergone a perceptive transformation over the years. They’ve been co-opted by right-wing outlets, who’ve enriched and endorsed them by smoothly incorporating them into their ideology, and as a result, the sheer violence that is being propagated in their names is unimaginable. Gandhi isn’t a linear figure for that matter, but he always advocated for nonviolence, which is getting erased increasingly with his appropriation.

This is not only a threat to society and women, but all the ‘lesser’ citizens of the country — be it Dalits, people of all genders and minorities, everyone.

While working on Assassin, what drove the narrative for you — the principal character or the larger setup which gives it a thriller-like quality?

In Assassin, the narrator is very much in control because readers are entering this world through her lens. It’s her experiences, her outlook, and her insights we’re offered. In that regard, I’d say that the conversations in this book, which are positioned matter-of-factly and as-is, are crucial. They have a technical role to play as they represent the post-truth scenario we’re witnessing. They indicate that facts in the current atmosphere aren’t sacred anymore.

There’s your truth, there’s my truth, and someone else’s. Each of us is choosing the truth we’re interested in, which benefits us, works in our favour, or suits our narrative. There’s no universal truth anymore. So, it was entirely character-driven.

Do you mean to suggest that people are choosing from a bouquet of truths or value systems, resulting in the atomisation that your character is also witnessing in Assassin?

What’s happening is the exact opposite. A single idea is being thrust upon you. There’s no opposition. Depending upon individual capacity, you are forced to either stretch or shrink yourself to suit the standard outfit getting handed over. Because it’s for nothing that knowingly or unknowingly everyone has accepted or is celebrating the everyday violence we’re witnessing. This glorification of violence is shocking. Diversity is being flattened out, as a conquering agenda is at play that wants to level things up, destroying the multidimensionality of our society and homogenising it to just a single idea. This was not the country that was imagined at its birth.

Given that you’re bilingual, what does the process of co-creating a translated work look like?

There are certain rhythmic patterns I follow. They’re there in Assassin, too, which J Devika has so wonderfully translated. As she can reimagine the story in her way, I call her my alter ego. This reminds me of a story of mine she was translating. I had used a word in it that translated to ‘ego’, but it was just the skeleton.

So, to convey the complete meaning and bring about the essence of the word I had used, Devika wrote it as ‘ego stilt’. This is how engaged and involved she is in preserving the beauty of the language she translates from.