Prof B N Goswamy is a distinguished art historian, scholar, and educator. His scholarship, experience, and eloquence flow through seamlessly in his short but engrossing essays - ‘slight sketches of large subjects’ — and culminate as Conversations: India’s Leading Art Historian Engages with 101 themes and More. The individual pieces, covering a wide range of topics relating to Indian art and culture, were published as independent, stand-alone columns over a quarter of a century in a national newspaper.

In a long career spanning five decades, Goswamy has befriended numerous artists, academics, collectors, and art connoisseurs either in person or through his research. Many of them come alive in his writings. The very first essay (published on July 14, 1995) features the Ceylonese historian and philosopher Ananda Kentish Coomaraswamy whom Goswamy considers to be ‘one of the subtlest minds of our century,’ and as one ‘who wrote like an angel.’

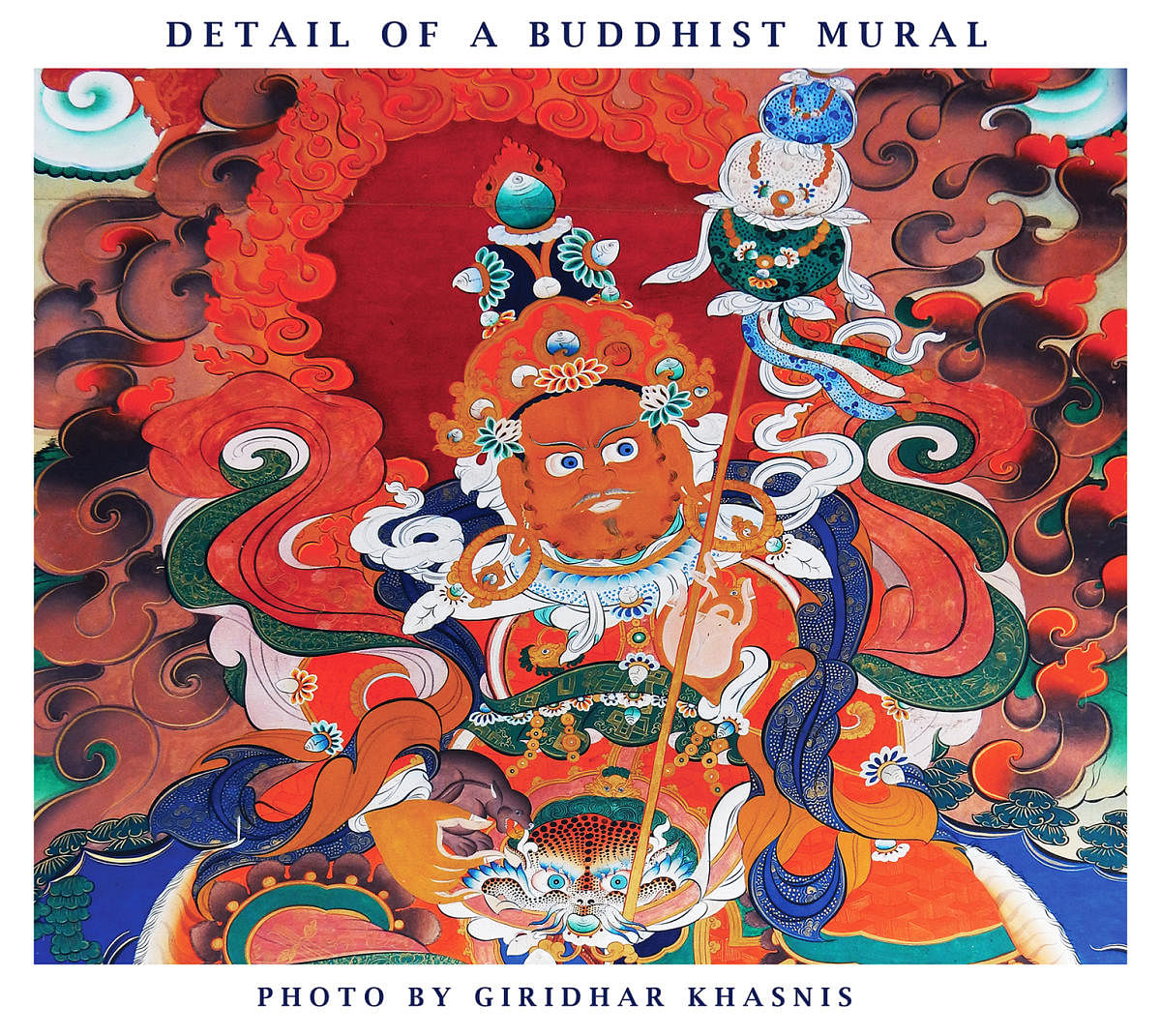

In the ensuing essays, he brings to fore unique facets of several other worthy personalities: Karl Khandalavala, the Parsi lawyer with his enchantment for the history of Indian art with its complex fabric of Hindu-Buddhist-Jain thought and iconography and mythology; the almost forgotten Bireswar Sen whose paintings were invested ‘with a light that never was on sea or land’; Rabindranath Tagore and his brooding art; and Gulam Mohammed Sheikh, whose work art is ‘drenched in colour, even as he takes the world on and treats of its pain and its anguish, its vismaya, and its countless contradictions, in the remarkable range of his work.’

Critical gaze

As the reader navigates the unique pathways of the book, what becomes evident is Goswamy’s special and undiminished admiration for anonymous artists and performers from little or lesser-known corners of the country — like the nameless painters in obscure little areas of the hills who create vivid, magical effects into their work by affixing hard wings of beetles found in their regions; simple-looking craftsmen with extraordinary levels of skills creating works of incredible elegance; Kathakali dancers who painstakingly prepare themselves ‘for entering the world of the gods’ and so on.

Goswamy’s critical gaze fixes on the sorry state of government libraries, museums, monuments, and the general lack of art appreciation in the public sphere.

He is rightly contemptuous of our penchant of ‘erecting larger than life-size statues of doubtful merit in public places and motley range of pathetic looking little ‘statues’ of Netaji or the Mahatma’ which could only delight ‘the hearts of the pigeons circling above for a perch. Or worse.’

He bemoans how the Great Ashokan lions have come to occupy the limp sheets of sarkari stationery ‘looking more like domestic pets than the kingly, Mauryan creatures that they once were.’

He is justifiably shocked when the innocent little ‘dancing girl’ from Mohenjodaro, no more than 4,000 years old, suddenly becomes an object of derision outraging the modesty of many of our countrymen. “In the vulgar times in which we live, she seems to be causing mortal offence… (although) there is not the slightest hint of obscenity in her, nothing explicit, no undue emphasis on her sexual charms, no suggestion of lewd intent.”

Right to paint

Speaking of another controversy, Goswamy wonders why there is talk only of the undraped female form when it comes to some sensibilities being offended. About M F Husain attracting a lot of wrath for his rendering of Goddess Saraswati, Goswamy writes: “I am no great admirer of Maqbool Fida Husain, certainly not of what he has become. But I would defend his right to paint the way he does. I do not find his rendering of the goddess Saraswati offensive or irreverent. There may be a touch of vulgarity in the manner in which he equated Ms Gandhi with Durga, or in the visual and verbal puns he used in obsessive paintings of Madhuri Dixit, but none in his rendering of Saraswati. Neither in respect of intention nor of context. What are the concerns of our emerging thought police, our street censors? Art is certainly not a concern: it seldom is. Is religion in itself a concern? I doubt it. Money? Not for the moment. But power is, and that, in our set-up, comes through politics. Politics then is the real concern. (Needless to say, if power comes, can money be far behind?) We are living in worrying times.” This was written in his column in 1996!

Goswamy’s essays are short, crisp, candid, and revealing. His commentary on the goings-on in and outside the world of art, literature and culture peppered in good measure with surprising facts and unheard stories is truly enlightening. His description of museums, exhibitions, art/craft/textile collections, chance encounters, and warm friendships is spotless. Quotations from classical texts and other material, when used, are perfectly contextual. Many of his essays even acquire the tone of poetry.

Having said that, some essays seem too short to be impactful. The reader would have liked a more elaborate narration about important artists such as the Bengali Masters, the Progressives, and others. One would have also vastly benefitted from the good professor’s frank comments on contemporary artists and modern trends.