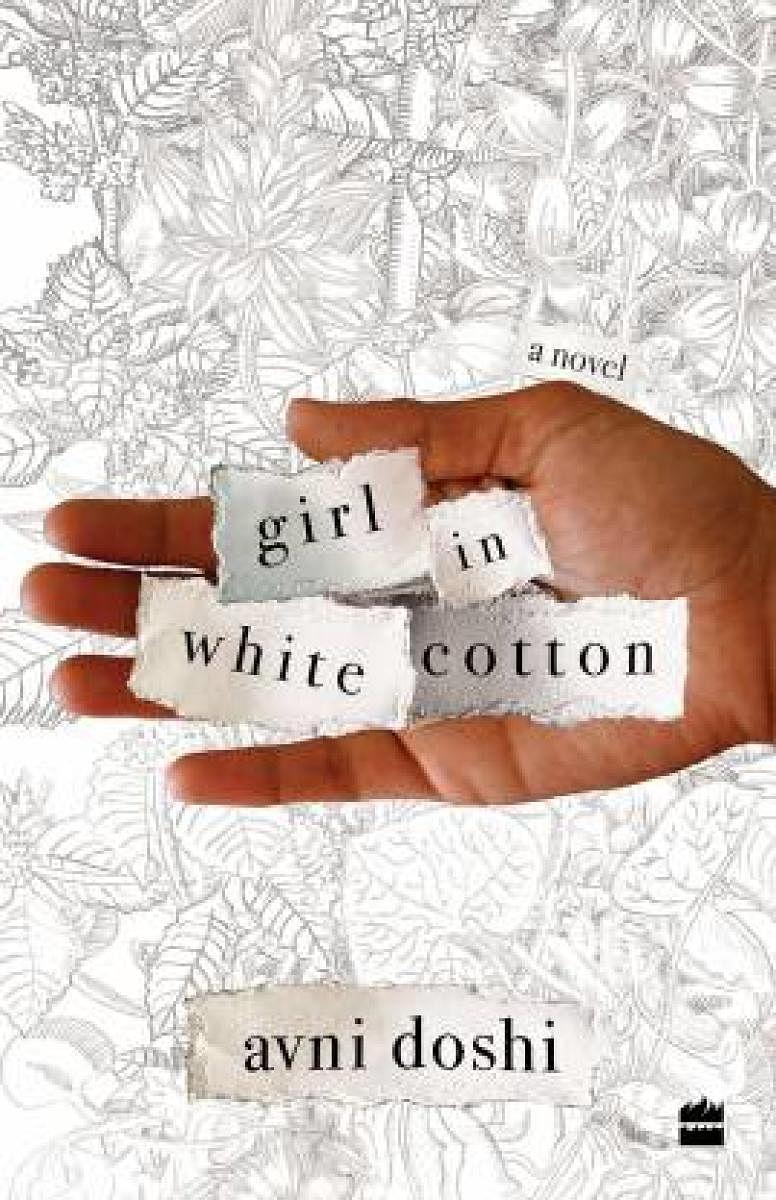

Mother: A loaded word in nearly every culture, carrying along a raft of formulaic associations, yet somehow retaining its mystique. While fathers give us a name and place in the outer world, in the cryptic interior, it is our mothers, with their power to nurture and destroy, who wield enormous influence. The revelation, for a daughter especially, that one’s life can easily become an extension of one’s mother’s life, a double image of sorts, unless there is a conscious effort to inhabit a separate world, is the start of the individuation process. The dynamics of mother-daughter relations have led to outstanding novels like The Joy Luck Club by Amy Tan, Beloved by Toni Morrison, White Oleander by Janet Fitch. A recent addition to the tribe is Avni Doshi’s debut novel, Girl in White Cotton.

The opening sentence, “I would be lying if I said my mother’s misery has never given me pleasure,” sets the tone for this story which is about an uncaring mother and her tainted relationship with her daughter. However, it’s also about memory, its reconstruction, its shifting nature and its ability to alter identities. In a nutshell, it’s the story of Tara, an unconventional woman, who has begun to forget — presumably due to Alzheimer’s though we aren’t quite sure— and the effect this has on her daughter.

Antara, the first person narrator, who is also the caregiver, has “suffered at her hands as a child,” and now regrets that there is “no way to make her remember the things she has done in the past, no way to baste her in guilt.” Troubled by her mother’s history Antara seeks to make peace, by reconstructing, through writing, incidents from Tara’s life on little scraps of paper that she tucks into corners where she hopes they will be discovered. Tara, who does discover them, merely comments, “I cannot believe a child of mine could have such bad handwriting.” Proving once again that our mothers are rarely the mothers we would like them to be. In this story, Tara repeatedly confounds Antara by the life-changing decisions she has taken: leaving a loveless marriage; walking straight into the arms of a spiritual guru, known only as Baba, “who travelled in a Mercedes Benz and collected VHS tapes of Brigitte Bardot films”; leaving Baba’s ashram to beg outside the Poona Club; packing Antara, who is more of an appendage than an offspring, to a boarding school in Panchgani, and taking up with a younger man, an unknown photojournalist named Reza.

Old photographs and old clothes are the means by which Antara evokes her mother’s chequered past. Discovering a pile of white clothes lying on the shelf below the stiff red silks of the marriage trousseau, she says, “If I hold them, I can still smell her body, as though she wore them just yesterday. I can smell the neglect, the damp, the misery that grows in the absence of sunlight…The whites are still bright, some glaring and some almost blue, the whites of widows, of mourners and renunciants, holy men and women, monks and nuns…Maybe Ma saw this white cotton as the means to her truth, a blank state where she could remake herself and find the path to freedom. For me it was something quite different…”

With Pune as its backdrop, time and memory as the dominant tropes, the narrative drifts back and forth between the city of the 1980s, and the present day. Despite the plethora, however, no character quite remains with the reader. What one is left with instead, is the litany of psychological upheavals, the twin crises of identity, the fraught nature of the mother-daughter relationship. “She named me Antara, intimacy, not because she loved the name but because she hated herself. She wanted her child’s life to be as different from hers as it could be. Antara was really Un-Tara.” The aim may have been to plunge the reader into an intimate reading experience, but the interiority is a bit too abrupt, focusing, as it does, on banal details that slow down the pace. A good debut, but not quite as striking as it could have been.