Three Indian-language translations (Hindi, Marathi and Malayalam) of Gun Island by Amitav Ghosh, a novel published in English barely 18 months ago, were released recently. A Bangla translation will also follow shortly. The speed at which these translations made it to the market is a happy surprise, to put it mildly. While in the past, popular novels have been quickly translated, this is a first (of sorts) for a literary novel, an acknowledgement of the awareness and interest in English works by audiences who prefer reading in their languages.

In another first, a Bhojpuri novel, originally published in 1977, Phoolsunghi, written by well-known Bhojpuri writer, Pandey Kapil, has been translated into English by academic Gautam Choubey. Bhojpuri, a historically rich language, has for the most part since Independence, been subsumed under the label of ‘Hindi’, much to the chagrin of its many speakers. In recent times, the Bhojpuri language movement has re-emerged as an important act of cultural assertion. This act of the opening up Bhojpuri literature to a larger audience is bound to have positive ramifications as well.

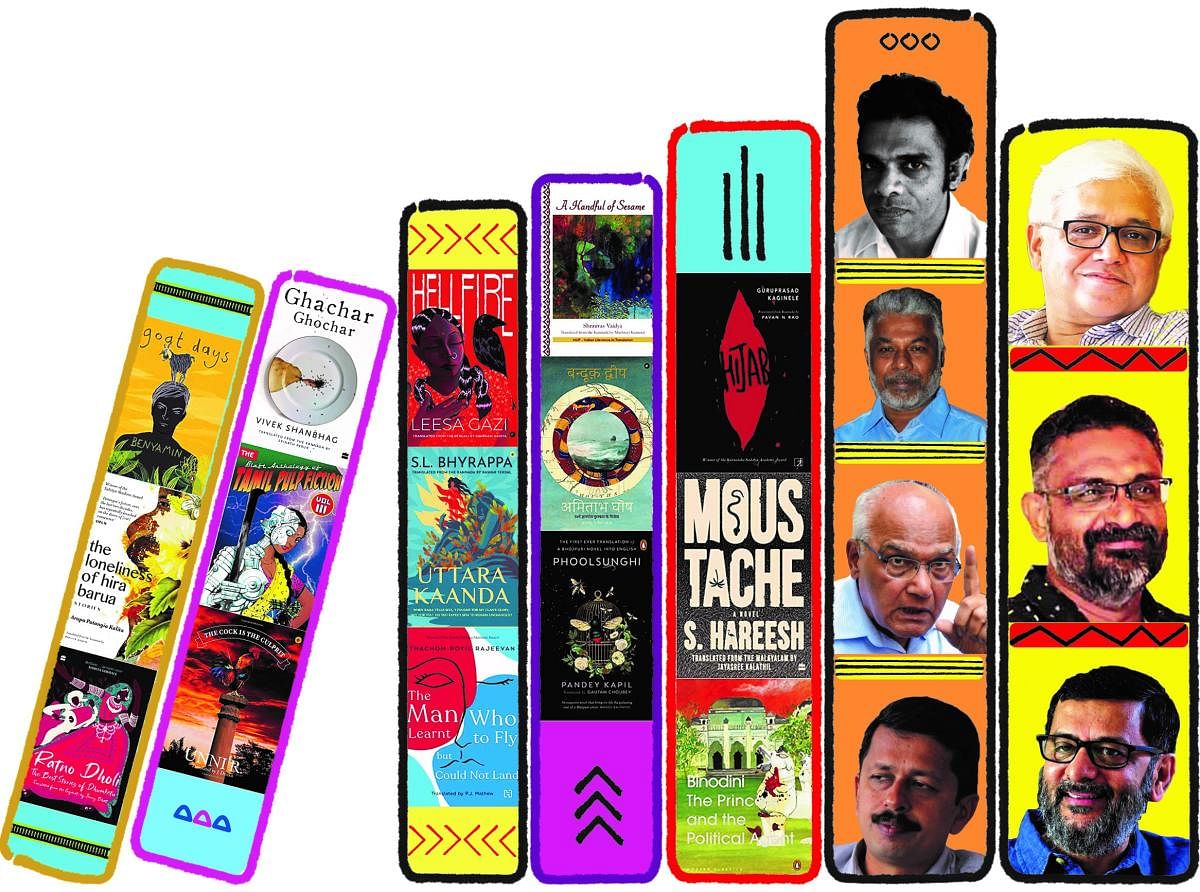

Coming on top of a scenario wherein translations have won the prestigious JCB Literary Prize twice in three years (Jasmine Days by Benyamin in 2018 and Moustache by S Hareesh in 2020), it might not be an exaggeration to declare that as far as literary activity is concerned, translations have never had it better. More people seem to be interested in translations, more

translators are actively translating and in general, translation has come to occupy an important place in the country's literary landscape.

Entry of big publishers

The word ‘translate’ comes from the Latin ‘translatio’ where ‘trans’ means ‘across’ and ‘latus’ means ‘carrying’—‘translate’ therefore means the carrying across of meaning from one language to another. The translation of the Hebrew Bible into Greek in the 3rd century BCE is regarded as the first major translation in the western world.

In the Indian subcontinent, where people have lived amidst several languages as a matter of course, translation is viewed very differently. For one, many prominent literary works have been composed in two or three languages. Kalidasa’s characters spoke in Sanskrit and Prakrit, for instance. The linguist, G N Devy calls this a ‘translating consciousness’. In the medieval period, the Mughals commissioned many translations of the epics. Dara Shukoh famously translated the Upanishads and the Bhagavad Gita into Persian.

In the colonial period, translation from the Indian languages into English become a widespread phenomenon both for the purposes of enquiry and the more prosaic purpose of administration. Charles Wilkins was the first to translate the Bhagavad Gita into English in 1784. Sir William Jones, translated Abhijnanasakuntalam (Sacontala or The Fatal Ring was his rather exotic title) into English in 1789. These translations were undertaken to help the British understand India better.

Since Independence, the Sahitya Akademi has pioneered translations from Indian languages into English, something that the Katha Trust also carried on with great success. But, with the entry of bigger publishers into the translation space and the commercial success of many of their releases, especially in recent years, translations have now claimed far more of the mind space than they ever did.

Unpacking the process

Among recent translations that have made a mark, Vivek Shanbhag’s Ghachar Ghochar, originally published in Kannada in 2013 and translated into English in 2015 has stood out, not only as a work of literary merit, but also on account of its international acclaim. Another writer who has become well-known nationally and abroad on the strength of his translations is Tamil writer, Perumal Murugan, author of Poonachi, Estuary and One Part Woman among others. Murugan initially came to national attention, when in 2014-15, there were protests in Tamil Nadu against his portrayal of certain religious practices in Maadhorubaagan (translated into English as One Part Woman).

This resulted in heightened interest in his work and translations of the controversial work and other books soon followed. He has, since then, won many awards and attracts attention almost on par with writers of commercial novels.

Talking to me about the process of translating Ghachar Ghochar for an English audience, Shanbhag unpacked the creative process that resulted in the creation of this path-breaking work. Shanbhag himself initiated the English translation and found in Srinath Perur, a translator, who truly understood his work. Shanbhag stated rather pithily that translation was not merely the act of translating the words on the page from one language to another. It was, he said, the act of bringing in ‘the unsaid from one language to another’. To this end, Shanbhag and Perur had several discussions around the text, not so much on the specifics of words and phrases, but more to unearth what was beneath what he had written in Kannada.

While Ghachar Ghochar was an instance of a writer himself interested in having his text translated, most translations begin at the opposite end — with a translator coming across a text that sparks off an interest in making it available to a wider audience.

Maithreyi Karnoor, translator of Shrinivas Vaidya’s Halla Bantu Halla from Kannada into English (published as A Handful of Sesame), began translating when studying for her Masters. But translating Vaidya’s work was something of a plunge into the unknown. She did not have a publisher when she began the difficult task of rendering the work, which had been written in a North Karnataka Kannada dialect into English. What attracted her to this particular work? Among other things, it was the fact that it was written in her own mother tongue, a Kannada dialect specific to parts of North Karnataka, which was at a distance from standard Kannada. Karnoor has since gone on to translate the plays of H S Shivaprakash, including the renowned Manteswamy, which was largely in verse and extremely tricky to translate.

Gautam Choubey, grandson of Bhojpuri litterateur, Chandradhar Pandey, grew up listening to his mother reading from Bhojpuri texts. Post his PhD in English in 2017, Choubey felt a gnawing need to reconnect with his mother tongue. The discovery of Phoolsunghi was accidental, but having read the text, he felt the need to share it with the larger world since the messages it conveyed were those, he believed, highly relevant to these fractured times.

The art of choosing

Given the wealth of literature that Indian languages hold, how do publishers make their choices?

Minakshi Thakur, who oversees the translation imprint, Eka, at Westland Books, and recently published Gun Island in several languages, says she looks for innovative texts, hailed for their freshness in the region of their origin, which will introduce entirely unknown contexts to the reader in the target language. Having identified such texts, she works closely with translators who are able to recreate the essence of the original text in a new language.

Teesta Guha Sarkar, Senior Commissioning Editor from Pan Macmillan, who has overseen translations such as Rita Chowdhury's Chinatown Days and K Madavane's To Die in Benares, says that manuscripts of translated works are evaluated in nearly the same way that other submissions are — by gauging quality, relevance, literary value and commercial viability. An additional criterion is the quality of the translation itself and its faithfulness to the author's voice, style and purport. Himanjali Sankar, Editorial Director at Simon and Schuster, who published Hijab by Guruprasad Kaginele recently, is of the view that a work has to have a contemporariness to it along with an evocation of the flavour of the region.

The need for contemporary works is also underlined by literary agent, Kanishka Gupta, who explains it in part by stressing that literary prizes do not consider translations of older works and also the fact that most Indian publishers (barring Penguin) don’t have a classics list.

A few exceptions to this exist though. The recent translation of the old Gujarati writer Dhumketu’s (1892-1965) short stories, entitled Ratno Dholi by Jenny Bhatt, is a case in point. Translations from Sanskrit too buck this trend since contemporary Sanskrit works are few. The foremost translator of Sanskrit works in recent times has been the venerable A N D Haksar, who has several translations to his credit. On the anvil, Kanishka says, is another classic — the translation of a major Hindi giant’s recently discovered play.

How the market responds to these works besides the other obvious need for recognition through a prize for translations of the classics could well determine the direction that translations of classic works will take.

The challenge of poetry

To the translator, poetry presents a unique challenge. To render into any other language, the nuances and cadences of verse is a big ask. In recent years, H S Shivaprakash’s renderings of the vachanas (I Speak of Rudra) and M L Thangappa’s of Sangam literature (Love Stands Alone, Red Lilies and Frightened Birds), a territory first traversed by A K Ramanujan many decades ago, have brought the attention back to poetry. In addition, the Murty Classical Library has published translations of more than 20 medieval classics, many of them poetical works. Their interesting format of presenting both the original text as well as the translation on facing pages has enabled engagement with both languages.

Still, translated poetry in book form is scarce, with magazines and online literary journals being the preferred vehicle, if one wishes to access them. An interesting upcoming translation is Jnanpith Award winner, Kunwar Narain’s poems, which are being translated by his son, Apurv Narain. (Disclosure: I am involved in the editing of this work).

What about children's literature?

On the children’s literature front, not too much seems to be happening in terms of translations of contemporary works. Much of the translations, it seems, are of the classics — Sukumar Ray, Satyajit Ray and many others. Contemporary children’s literature in India lacks well established national names, with the exception of Sudha Murty and Ruskin Bond (both of whom write in English) and that in part explains the paucity of translations. But, on the positive front, Pratham Books’ StoryWeaver, a digital platform that provides open and free access to quality storybooks in multiple languages, is an interesting experiment. StoryWeaver has also embedded simple tools on the platform that allow users to further translate the books for localised requirements.

A case for non-fiction?

While fiction has been translated extensively into English from many Indian languages, the same cannot be said of non-fiction. Interestingly, Aharnishi Prakashana has published in Kannada, Vinod Mehta’s Lucknow Boy (Lucknow Huduga) and Neyaz Farooquee’s The Ordinary Man's Guide to Radicalism (Padakusiye Nelavilla). The onus is now on publishers to do the same thing in English since non-fiction in regional languages is considerable.

Also, besides Amitav Ghosh, translations of literary fiction from English to Indian languages is limited. Could there be a case for looking beyond the literary into the frenetic world of pulp fiction from the languages, like the volumes of the Blaft Anthology of Tamil Pulp Fiction and translations of Ibn-e-Safi (from Urdu)? Perhaps, the largest opportunity exists in translations between languages without the mediation of English, especially of ‘adjacent’ languages like the south-Indian languages or between Hindi and Punjabi, Gujarati and Marathi and so on. That would perhaps be the true apogee of our ‘translating consciousness’.

The author is a publishing professional who writes on literature, language and history.