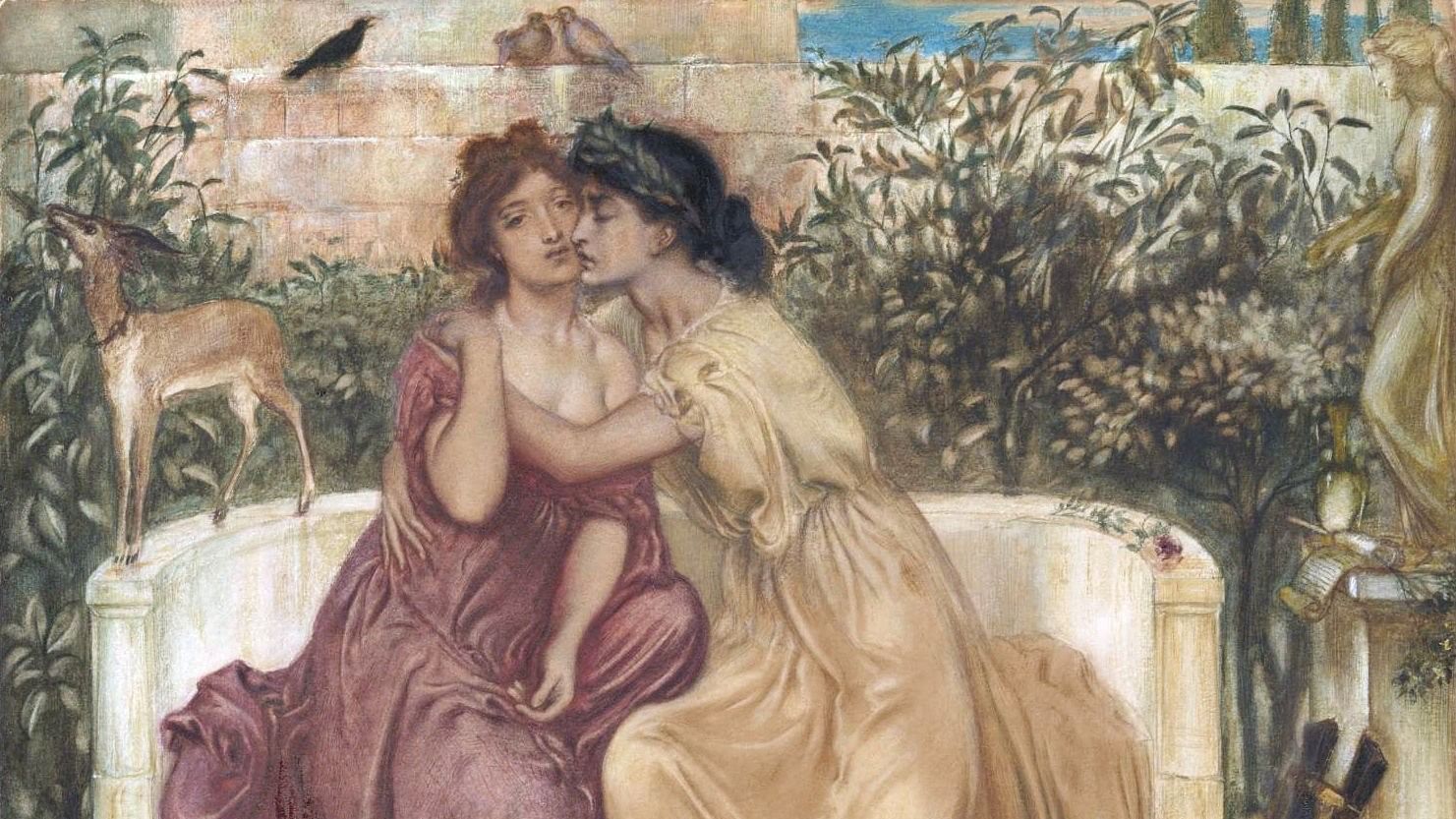

Sappho and Erinna in a Garden at Mytilene’ is an 1864 painting that is perhaps one of the first depictions of same-sex female desire made for a gallery-going audience in the West by painter Simeon Solomon, a Jewish artist from Victorian England.

Credit: Wikipedia

From bone-chilling evenings to sunny afternoons; from navigating the visually inhibiting foggy weather to finally witnessing the vibrant and lush bloom of marigolds, March doesn’t simply herald the transition from winter to spring; it is also a celebration of Women’s History Month in the United States and International Women’s Day globally on March 8.

This year’s theme, ‘Invest in women: Accelerate progress’, seeks to shine a spotlight on the prevailing economic, social, political, cultural, and legal systems that perpetuate discrimination and prejudice against women, thereby constraining their full and unrestricted participation in society. One need not look any further than the United States, where abortion rights have been dwindling since the overturning of Roe vs Wade almost two years ago. The top court in Alabama recently passed a chilling new order, ruling that frozen embryos were “children” for the purposes of an Alabama law, leading several In Vitro Fertilisation (IVF) clinics in the state to shut down for fear of being subjected to lawsuits. Until a day before, these clinics were merely providing reproductive health services. But today, they could be culpable of “murdering children”.

Unlike in the United States, women’s reproductive rights in India are enshrined in the Constitution (see Shreya Singhal vs Union of India, 2015), but it took our Supreme Court nearly five decades to realise that the term “woman” as it appears in our national abortion law (the Medical Termination of Pregnancy (MTP) Act of 1971) also includes “persons other than cis-gender women who may require access to safe medical termination of their pregnancies.” (As decided in X vs Principal Secretary, Health and Family Welfare Department, Govt of NCT of Delhi and Another, 2022). The Court, thus, expanded the scope of the term “woman” in the context of abortion law in India through this judgement. And while this is significant, we must also be cognisant of the fact that not everyone shares these progressive views about gender. There is a raging debate in many parts of the world, especially in the West, about who constitutes a woman and whether transgender women are allowed to fall into this category. While Indian law puts transgender people, including transgender women, into a separate category, it is not clear whether transgender men and women can claim recognition in their biological categories.

Left out

In India, the issue of inclusion becomes even more pernicious because queer women have little to no rights compared to their non-queer counterparts and have been largely left out of the policymaking agenda; so much so that even broad and meaningful developmental goals like “women empowerment” and specific initiatives like “Nari Shakti” systematically overlook the very existence of queer women from its purview. “Women,” according to the Indian state, cannot be anyone who is not heterosexual or cisgender. If they are transgender, they must fall into a different category. And if they are homosexual, then they must be left out. While queer women may not be considered as “women” by the Indian state, they are lumped into the amorphous category of “people” — a group that possess formal, but not substantive rights under the Constitution. Thus, non-heterosexual women have the right to life, as guaranteed by the Constitution to all people. However, that right does not translate into the right to marry a person of one’s choice — the state has opposed it and won that argument in the Supreme Court (see Supriyo vs Union of India, 2023). Similarly, the Constitution confers non-heterosexual women with the right to dignity as well, but that doesn’t translate to an automatic right to access the remains of one’s dead same-sex spouse (because Indian law doesn’t view a same-sex couple as a “couple” or a spouse as a “spouse” the way it does for heterosexual people).

Except for transgender persons, queer women are also not specifically protected under any comprehensive anti-discrimination law. Thus, while the Supreme Court has made slow and steady strides in recognising queer people’s, and by extension, queer women’s rights over the years, governments have been either sluggish to respond or have outrightly refused to codify judicial declarations into binding law, despite the court exhorting the government to do so.

Need for codification

The state’s disdain towards queer people in general and queer women, in particular, is apparent by the fact that while the 2014 NALSA judgement led the Union government to enact the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act in 2019, there was no concomitant action by them to similarly codify Navtej and expand the rights of sexual minorities. Many of the recommendations posited by the Chief Justice in the marriage equality judgement read more like post-Navtej implementation guidelines and that is unfortunately so because the state refused to act proactively in the years following Navtej. As we stand today, there is no update regarding the status of either the review petitions challenging Supriyo or the high-powered committee meant to look into the legal demands of queer couples. The state apparatus, it seems, is simply not interested in protecting women’s rights as long as those women are queer.

Towards recognition

On September 22, 1971, the Government of India instituted a high-level committee to study the social, legal, and political status of women in the country. It led to the publication of a landmark report in December 1974, titled ‘Towards Equality’ which highlighted the myriad ways in which the state apparatus left women behind. Chapter 4 of the report, titled ‘Women and the Law’ specifically foregrounded the need for comprehensive legal reform to protect women’s rights. Surprisingly, not a single page was dedicated to the status of queer women.

Five decades later, we’ve come a long way: homosexuality has been decriminalised, transgender people are entitled to the same rights as their cisgender counterparts, the Draft National Menstrual Hygiene Policy, 2023 includes transgender and non-binary people, and our abortion law now covers both non-cisgender women and survivors of marital rape under its ambit.

And yet, marital rape itself is not recognised as a crime under the new criminal law codes; same-sex couples have no legal right to marry or adopt; and customary practices within personal laws enjoy special immunity from judicial intervention, even if those practices are blatantly discriminatory.

Indeed, there is still a very long way to go before Indian women truly enjoy full equality. The problems are multifaceted, and reform initiatives have, over the years, been piecemeal.

Queer women, in particular, are at a significant disadvantage for they have been largely ignored by both the women’s movement and mainstream policymakers for decades, and only now are their issues slowly coming to the fore.

As another Women’s Day goes by, we must remember a promise made not very long ago at the historic G20 summit held last year in India — the first ever held in the country. With India’s leadership, the G20 committed to gender equality and promised to enhance “women’s full, equal, effective, and meaningful participation... across all sectors and at all levels of the economy.”

But this promise will mean nothing if the G20 (of which India is a part) continues to ignore queer women’s needs.

(The author is a Communications Manager at Nyaaya, the Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy and can be reached at sahgalkanav@gmail.com)