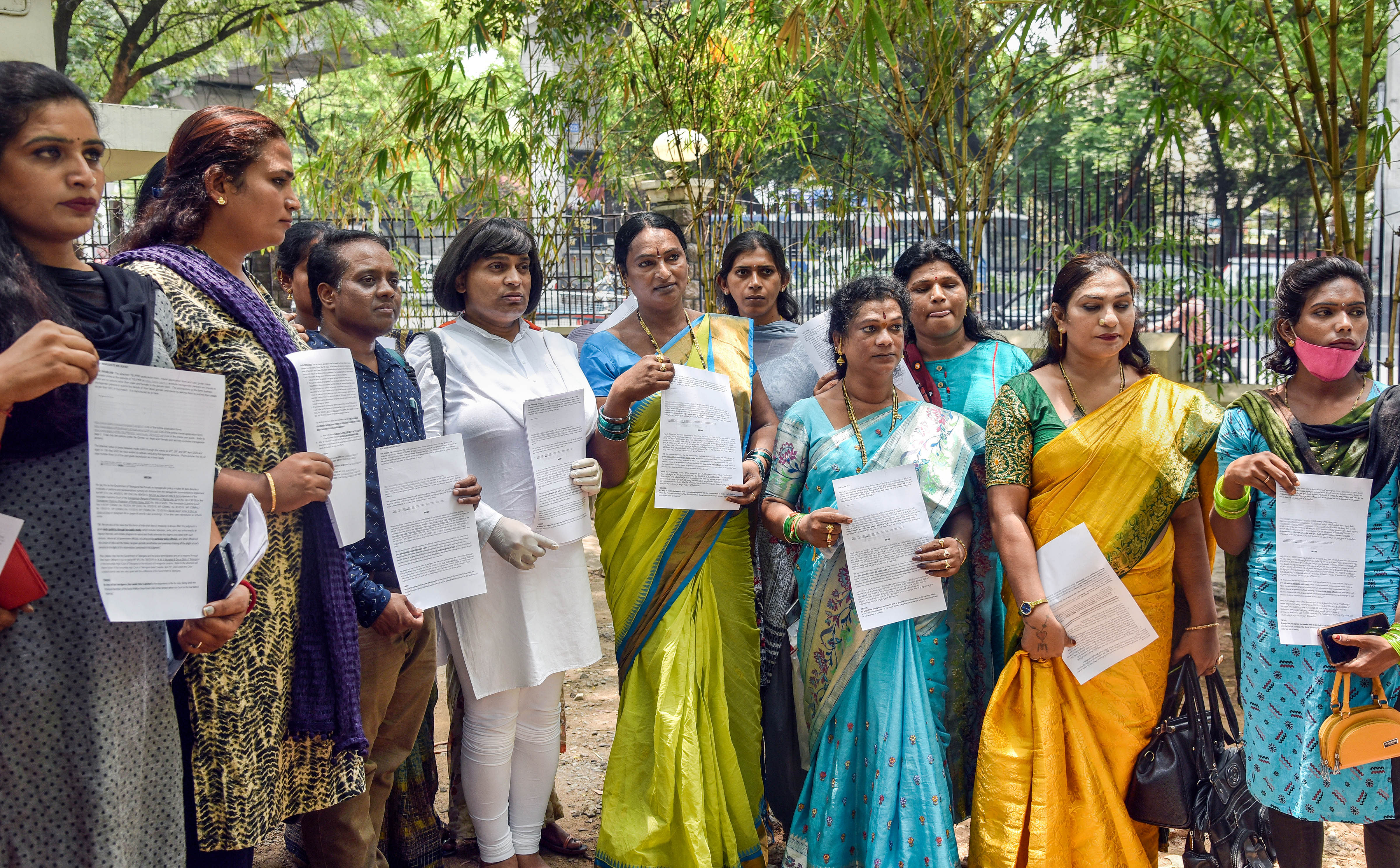

File photo of members of the transgender community submitting a memorandum to the office of the DGP in Hyderabad demanding an ‘others’ column (in the gender section) in job application forms.

PTI

The transgender community in India has been historically marginalised. It was in 2014 in the NALSA judgement that the Supreme Court definitively gave judicial recognition to the community by recognising the right of transgender persons to determine their own gender. The state and the central governments were also directed to give legal recognition to their gender identity as male, female, or third gender.

The governments have done this to some extent. However, the judgement also contained a direction to the governments to treat the community as socially and legally backward and to provide for reservations in admissions to educational institutions as well as in public appointments. The affirmative action programme was ordered so that the ‘injustice done to them for centuries could be remedied’.

This was exactly the same logic which formed the basis for reservations in favour of the scheduled castes and tribes. What is interesting is that the nature of reservations required to be given to the transgender community is a slight departure from those given to members of the lower castes. Reservations can be of two types — vertical or horizontal. Vertical reservations are how a regime of affirmative action is traditionally understood.

Thus, a fixed percentage of the total available jobs are reserved in favour of a caste or any other defined class. Therefore the 22 per cent reservation of government jobs for the scheduled castes would amount to vertical reservations. Horizontal reservations are different. Over time, different castes and groups have varying portions of reservation — the job pie, so to speak, is divided into slices of different sizes.

However, there could be disparity within these groups as well. For instance, women or the disabled as a class are likely to have been discriminated in whichever caste group they are found. Therefore, to accommodate for this kind of generalised discrimination, the law provides for horizontal reservations where a fixed percentage of each caste quota is further reserved for the discriminated class.

For instance, persons with disabilities are entitled to 4 per cent of posts irrespective of their reserved category. This distinction between the two forms of reservation has a profound effect on how inequality is viewed between sections. Horizontal reservations have been seen as part of Article 16 (1) while vertical reservations are stated to be a facet of Article 16 (4). Of course, this is a slightly confusing statement of the law because as we saw earlier, the two clauses of the articles are meant to be a composite whole.

However, the implication probably is that the beneficiaries of vertical reservations (i.e. the backward and scheduled castes) operate in a sphere which is an exception to the general concept of equality whereas beneficiaries of horizontal reservation (women and the physically handicapped) deserve reservations because the very concept of equality demands it. This recognises the unique experience and the special form of discrimination faced by the beneficiaries of horizontal reservations.

The court in NALSA did not clarify whether the mandated reservations would be horizontal or vertical in nature. Members of the transgender community have urged that they should be entitled to horizontal rather than vertical reservations. An application was moved before the Supreme Court asking for clarification that the reservations mandated by the NALSA judgement were for horizontal reservations.

The court dismissed the application on procedural grounds holding that the petitioners ought to have filed a substantive petition seeking horizontal reservations rather than asking for the clarification of a judgement already passed. As of the writing of this book, this issue remains unresolved. Sadly, even though the court has directed the provision for reservations, it has largely been ignored. The Central Government has taken a stand that no reservations can be provided to the transgender community. Some state governments like Karnataka have provided for reservation, while most others have not.

The Transgender (Protection of Rights) Act, 2019, which was enacted pursuant to the NALSA judgement, does not provide for reservations, in clear violation of the Supreme Court order. Being politically disempowered seems to offer a reason for the government to ignore the demands of those who most need State aid. A heart-wrenching instance is that of Ms X, a bright student in a private school in Delhi who dreamed of being a doctor. She also identified as a transwoman and eventually came out to her family. In her twenties, she felt that her family was not supportive and decided to move out of her home and support herself through giving tuitions and other part-time jobs.

She was, in essence, a person who faced social stigma and yet fought on to realise her goals. Her dream was to specialise in reproductive health. In an interview to a newspaper she said, ‘Since I cannot become a mother, I wanted to help others through methods such as IVF.’ She took the entrance test for the master’s programme conducted by AIIMS and secured the eleventh rank in the examination. Sadly, that rank was not enough to bag a place in her preferred course — MSc in Reproductive Biology and Clinical Embryology.

The course had seats reserved for various castes and the EWS category, but none for the transgender community. This was even though on most metrics, the transgender community performs worse than certain OBCs. Ms X has since moved the Delhi High Court seeking for implementation of the NALSA judgement. While the Centre denies and the court prevaricates, Ms X has no place to turn to — she is the child of a lesser god.

(An exclusive excerpt from 'Who is Equal' authored by Saurabh Kirpal, a senior advocate at the Delhi High Court. Penguin Random House India recently published the book.)