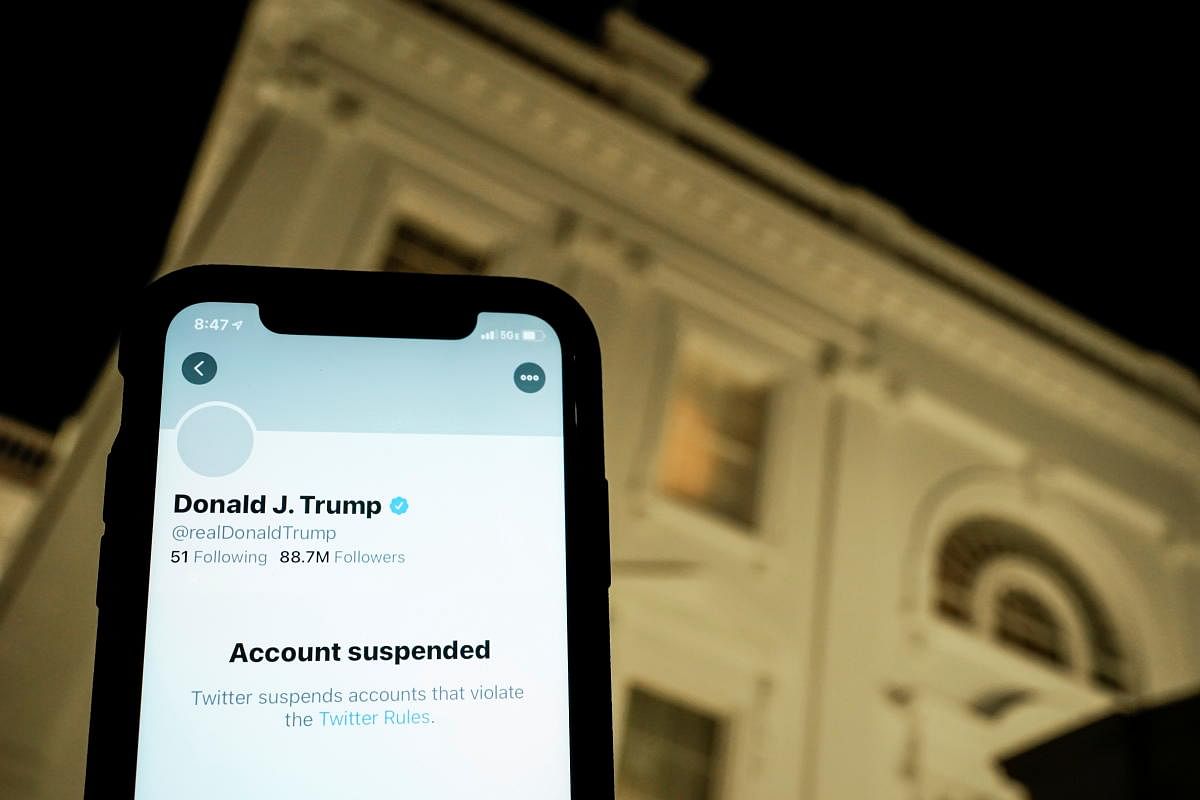

Some of the most fascinating stories about the internet are buried in boring legal documents that most people will never read. When Twitter banned Donald Trump earlier this year, people worldwide argued about whether platforms like Twitter should have such power. It was a fair question; if Twitter and Facebook could ban the leader of the free world, what was stopping them from banning politicians in India?

To understand why Twitter could ban Trump without severe consequences, there is some value in taking a closer look at the law which makes it possible and how it originated. Our story begins in North Dakota in 1956, where a Senate campaign in the US was being contested by Republican candidate Milton Young and Democrat Quentin Burdick. A few days before the election was supposed to be held, Arthur Townley (Independent) decided to make a controversial speech slandering his opponents and talking about a farmers’ union. And so he approached WDAY, a television and radio broadcaster.

WDAY recognised that the speech was controversial, but was bound by regulation to give candidates equal air time and let the speech air. As expected, the content did not go down well with his opponents and the union he mentioned in the speech. The latter decided to sue Townley. Probably recognising that suing Townley alone would not be very financially rewarding, the union also decided to sue WDAY, the network that aired the speech.

The matter made it to the Supreme Court, and they ruled in favour of WDAY. Cases with similar themes began popping up across the United States. If the broadcaster could not be held liable for the speech it was airing, could a bookstore be held responsible if it unknowingly was selling a controversial magazine? At the time, the decision from the Supreme Court and the American Judiciary was that the broadcasters and bookstores could only be held liable if they made active efforts to edit the content they were hosting.

Conversely, this also meant that to avoid any liability, platforms such as WDAY (and Twitter today), had an incentive not to moderate any content they aired or hosted. If none of the platforms controlled what was posted on them, they did not need to worry about being vulnerable to such lawsuits.

Shifting gears

Acknowledging how the lack of moderation could backfire on the rise of the internet (which was yet to emerge as an industry in the 1990s), Congressmen Chris Cox and Ron Wyden drafted Section 230 and got it passed in relative obscurity. Since almost no one in the Congress had a clue why this was important, the bill got passed without any opposition. The bill’s idea was that platforms like Twitter could moderate content hosted on them in good faith and not be held liable. So, they could remove someone powerful, like the then President Trump for inciting violence.

However, people have recently been dissatisfied with the amount of moderation platforms have engaged in. Depending on where you stand, it has been either too much or too little, and the gears are starting to shift on Section 230 in the US and India.

The US has been considering amendments to Section 230, as has India. As governments

get more aggressive in ordering Twitter to ban accounts, the debate around how much platforms should moderate has taken centrestage yet again. For better or worse, the amendments to these laws will be passed in anything but obscurity. There is no guarantee either that big tech will come out on the other side unscathed.

The writer is a policy analyst working on emerging technologies. He tweets at @thesethist

Tech-Tonic is a monthly look-in at all the happenings around the digital world, both big and small.