It is a regular, breezy Sunday when I embark on a four-hour road trip from Mumbai to Pune to taste one of the most ancient forms of alcohol to exist in the world. It is believed that the Vikings guzzled it down for strength before stepping into battlefields. It existed in Greek and Roman cultures too, and in China since 7 B.C. The Ethiopian version is called tej, while indigenous variations exist in Coorg, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Ladakh and stretches of the northeast even today. “How many of you know what mead is?” Nitin Vishwas, co-founder of Moonshine Meadery, Asia’s first mead makers, quizzes my group during a mead-tasting tour.

“A cross between a beer and a cider,” a Pune native responds from a crowd of 15 people. “A drink infused with beer?” asks another. “No,” Nitin protests whilst pointing at his shirt that declares ‘Mead is not Beer!’ We’re at the company’s site where the country’s first mead-making operations officially commenced in 2018, and as of January 2023, they’d recorded a production of 576 batches. Mammoth distillation machines and icy storage units occupy the factory space that leads to an alfresco-tasting area surrounded by jamun trees.

Mead’s moment to shine

“Mead comes from the Latin word medo, which comes from the Sanskrit word madhu, meaning honey,” Nitin clarifies. The humble drink is a mixture of honey, water, and wine or champagne yeast that is poured into a temperature-controlled tank and allowed to ferment over 45-60 days. When infused with fruits, it is called a melomel, and when mixed with spices or herbs, it becomes metheglin. The former is a popular means of food preservation, keeping summer produce for the winter, while the latter possesses medicinal properties and comes from the ancient Welsh words Meddyg, meaning healing, and Lllyn, which means liquor. Many meaderies in Europe are known to take around eight months to make a batch, but India prides itself on developing a formula that seals the deal in seven days. “In fact, we’re working on a technique to complete a batch in just four days,” Nitin reveals.

Legend has it that the Ottoman empire discovered distillation and gifted the idea to different cultures. Whiskey in Turkey was traded for feni in Goa. When the British brought with them spirits, mead was overshadowed, and over time, it disappeared from the radar. It wasn’t until recent years that the drink saw a resurgence, especially in the US around 2016-2017. “Every other form of alcohol has had its moment under the sun,” Devashish Sutavani, the special projects manager tells me. “What goes out of style eventually comes back. Now it’s mead’s moment to shine.”

The eclectic blend

The journey hasn’t been particularly easy in the Indian context. Up until 2017, meads did not even exist in the production category. Nitin, along with his childhood friend turned business partner, Rohan Rehani, put the framework in place and pushed the government to legalise it. The brewery’s operations started out of their own kitchens in 2016 before moving to a tiny shed in Pirangut, Pune two years later. Rounds of experimentation continued with machines and techniques before nailing the flavours. Grilled pineapple, mango chilli, chocolate orange, Thai ginger and kafir lime, coffee, salted kokum, and Christmas-special apple and cinnamon meads became tried and tested favourites. Hibiscus ginger and strawberry meads are the latest in the making, while the seasonal jamun from the premises is reserved for the team only. The use of real fruits (along with the fibres), naturally-sourced honey, and the lack of preservatives explains the rich citrusy notes and the clear consistency of the drinks, which go through three levels of filtration before settling at 6.5 per cent alcohol.

When asked if mead has a shelf life, Nitin answers in negative. Similar to wine, it is believed to get finer with age even after being bottled. In fact, a bottle of mead contains more antioxidants than a bottle of red wine.

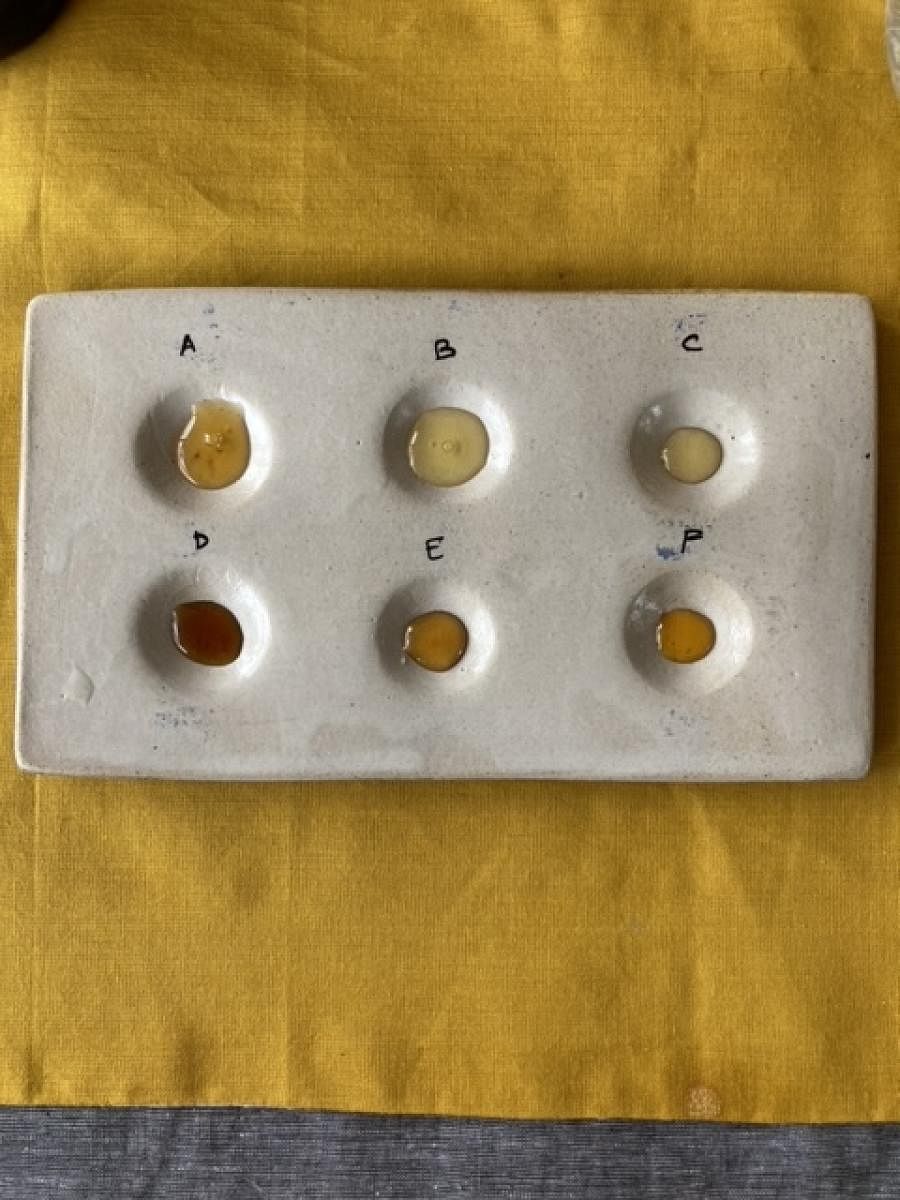

The A, B, C, D, E, F of mead

We move to the outdoor area to indulge in a honey-tasting session. A palette with six categories, labelled A to F, is placed in front of each of us. I learn that when honey is packaged for retail, multi-floral honey yields greater quality and health benefits as opposed to monochrome varieties of which mustard honey is the most common. It is also said that pure honey does not crystallise over time. We’re encouraged to scoop a dollop of each category, and test its viscosity or the lack thereof before relishing it. ‘A’ is a multi-floral honey that is deep golden in colour and tastes like most store-bought honey. It also forms the base for most meads at the factory. In the case of ‘B’— acacia honey, sourced from acacia trees near the Chambal River in Teepri, Rajasthan — the sweetness does not linger and the texture is less viscous. ‘C’ has hints of lemon and mustard, while ‘D’— a tribal honey from Palghar — is dark in appearance and laced with pungency. In the case of ‘E’, we’re asked to lift a large scoop and look for perfume notes. I sense rosewood. ‘F’—cider honey — has notes of toffee, butterscotch, and caramel. Each bottle of mead uses a combination of these kinds of honey; the nectar is extracted in-house from existing farmlands and beehives with the help of a designated beekeeper, making it a largely sustainable operation.

Finally, we take swigs of the coveted drink. Cold, citrusy, sweet, and spicy — a complex range of textures and flavours reveal themselves with each sip. It’s nothing like beer and I reckon the movement is here to stay.