School textbooks routinely refer to the Mughal emperor Akbar (1556-1605), as ‘Akbar the Great’, so much so that school children may be forgiven for thinking the epithet is part of the emperor’s name. In the firmament of historical stars, Akbar would arguably be next only to Ashoka, who preceded him by 17 centuries, both allowing their empire-building instincts to be interrupted by periods of reflection, of the questioning of received wisdom to venture into the fraught area of religious reform, of attempting to provoke new ways of thinking in their subjects.

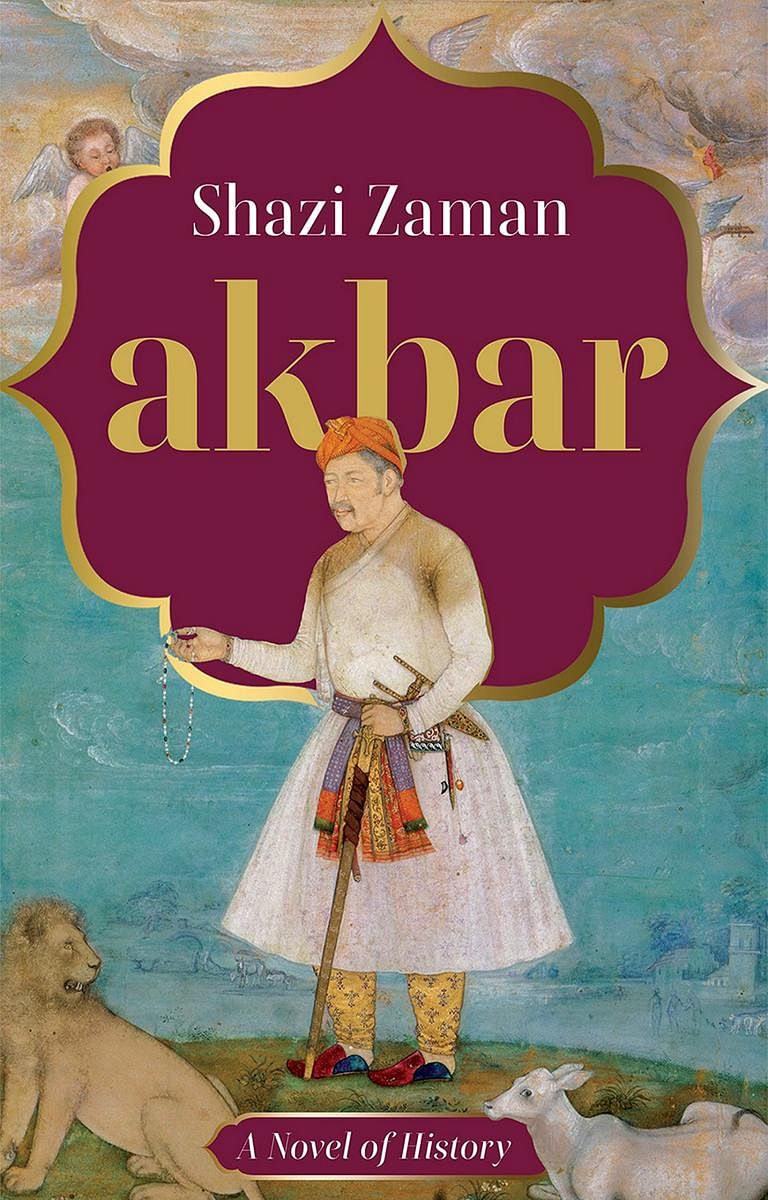

Written originally in Hindustani, this English translation calls itself ‘A novel of history’. The formidable arsenal of historical sources the author has consulted is in evidence, situated in a creative framework. “Where sources fall short or silent,” he asserts, “I have exercised the inalienable right of a novelist — that of imagination.”

The novel chronicles the main events of emperor Akbar’s reign, not necessarily in chronological order. The emperor is shown in all his dimensions: pragmatic, whether in the decision to shorten the length of his kurta after his father Humayun caught his foot in the hem of his upper garment and tumbled to his death, or in binding the allegiance of the restive Rajput kingdoms with matrimonial alliances; looking to ally rather than confront, but decisive, unrelenting and even cruel where the expansion of his dominions was concerned or when he felt slighted.

While the work lays out the panoply of historical figures of the period, including Akbar’s predecessors and successors, faithfully recalling the twists and turns of Akbar’s fortunes, the life “spent in the shadow of conspiracies”, what concerns the author in the main is Akbar’s state of mind, the possible cogitations that led to his not just seeking to bring harmony among his diverse subjects but to goad them to free themselves from bigotry, and finally to establish a new religion. A work of this nature calls for ambition in conception and nuance in approach, and the novel acquits itself admirably on these counts. The book is organised into two parts. Part 1 centres around the emperor’s camp at Bhera, on the banks of the Jhelum, in the year 1578, the site of one of the biggest qamargahs or royal hunts and the author uses this event as an inflexion point in the turn of historical events. It is perhaps indicative of Akbar’s state of mind that he orders the multitude of animals, trapped preparatory to the hunt, to be freed, in keeping with the spirit that the foremost of a king’s duties is to grant life.

Part 2 of the novel, more coherent than the first, traces the emperor’s interactions with scholars and theologians of different persuasions, the fierce debates in the Ibadat Khana or the House of Prayer at Fatehpur Sikri whose doors were opened to all faiths after the Badshah returned from Bhera, the culmination of the path of amity or sulh-i-kul into the Din-i-Ilahi , the new faith proposed by Akbar.

While acknowledging the monumental task involved in working the rich material the author has at his disposal into a readable story — for a historical novel, it is not very lengthy, and illuminating little-known material with imaginative flares, this is a novel that makes the reader work hard. Writers are advised to use a judicious mix of “show” and “tell” in their narrative techniques, and this one errs on the side of showing, leaving the reader to connect the apparently random dots. The author makes room for this in his note — “In some places, the articulation of some characters can seem long-winded. I appeal to readers to be patient as it is important to understand the manner of articulation of those times to get an idea of the age.” This is an exercise perhaps that only the connoisseur of historical fiction would be willing to undertake, but the patient reader will be rewarded.