Astute yet sensitive, written with elegant style and delicious verve, these stories by Wajida Tabassum are seductively glorious. Expressing herself within a dominant culture, being a woman in a male-dominated society and staying independent within a tight-knit family, the stories alone carried her out of a murky hole to a meadow. Breaking free from an impoverished and forbidden life, she weaved prose that allowed her to navigate the world without fear despite her hushed sadness and repressed emotions. Credit to her ingenuity that she did not allow social intimidation to get the better of her creative instincts.

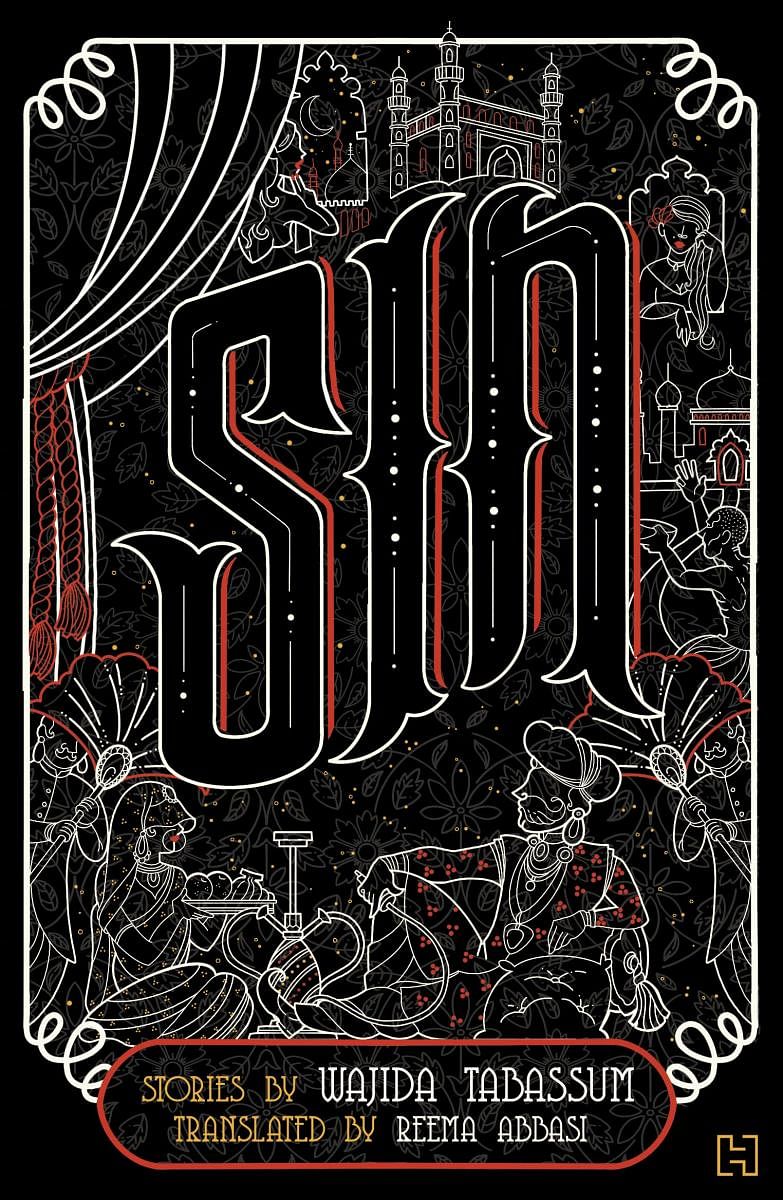

Translated into English for the first time by Pakistani journalist Reema Abbasi, this stellar collection of 19 short stories set in the old-world aristocratic society captures the entire range of the realities of middle-class compulsions and depravities indulged in by the social elite. Arranged under four sections — Lust, Pride, Greed and Envy — all that is a sin to others ends up as a triumph for the protagonist. Holding on to the force of its original rendition, Abbasi has translated the stories with flair and finesse to connect with the dilemmas that continue to confront women in modern times. ‘We are in a perpetual quest to find our voice and the courage to express what we really feel’. Wajida sets her women free to chase their freedom with a stubborn passion.

Asserting that Sin, like people, has many shades and facets, Wajida had hoped that the stories will be read and remembered as works of literature. Erotic with symbolic details, the women in her stories refuse to be puppets. Bearing a subtle resemblance to Ismat Chughtai’s Lihaaf, a begum revolts against her husband’s drunken sexual escapades in Hor Uper (Up, Further Up) by appointing a young boy to massage her. Replacing her gharara, a garment stitched between the thighs, with a long skirt called lehenga acts as a symbol of revolt. In Lungi Kurta, another tale wrapped around garments, a new bride exchanges clothes to take revenge on her husband’s betrayal. The stories make a smart, powerful, and very contemporary read that touches on the struggles shaping the very world women live in today.

Layers of emotions

In her lush and vivid prose, Wajida lets her women shed any threat of censure by society to take full ownership of their bodies. In doing so, she lets the reader confront the entrenched assumption that women lack the courage to radically liberate themselves. Through her own story, Meri Kahani, Wajida surprises readers with her rebellious fearlessness while being part of a conservative, demanding household. The consummate erudition is matched only by her creativity, and startling capacity for unfolding emotional layers. She wins the deepest admiration for it, while her vulnerability remains heartbreaking at the same time.

Each of the stories in this anthology captures the power of the subliminal with nuanced precision. Powerplay, betrayal, impotence and abandonment run through most of the stories, providing the backdrop for the downfall of the nobility. Zakat (The Alms of Death) and Joothan (Leftovers) reflect the nobility of the middle-aged Nawab Jung in poor light, who gets a lesson in charity from poor adolescent girls in the first and an eye-opening message on who survives on whose leftovers in the second story.

Considered a jewel of Urdu literature, Wajida demands to be read. Told in a sharp and evocative style, the stories in Sin examine the nature of domestic relationships, self-determination, and what it means to be a person. An entrancing pageturner, the stories have just enough to trigger the ultimate implosion. With notable exceptions, Wajida was a woman who did not so much express opinions or emotions but interrogated both. Reading her for the first time, I can safely say that she was a woman who mattered, very much. Such is the power of her prose that you can’t get her out of your head.