Mumbai, more than any other Indian metropolis, has been a long-time muse for fiction writers in English. We don’t know for sure when the first novel set in the city was written, but two works, both by Parsi authors, K E Ghamat’s ‘My Friend, The Barrister’ (in 1908) and Ardeshir and Dinbai Chinoy’s ‘Pootli, A Story of a Life in Bombay’ (1915), were among the earliest.

Though short on ‘literary’ quality, the books did provide a glimpse of suburban upper-middle class society and recorded key crises in the city’s history, such as the small pox and bubonic plague epidemics. In the intervening decades, authors of every ilk, from Salman Rushdie to Shobhaa De, have used the novel form successfully to tell remarkably different stories of Mumbai.

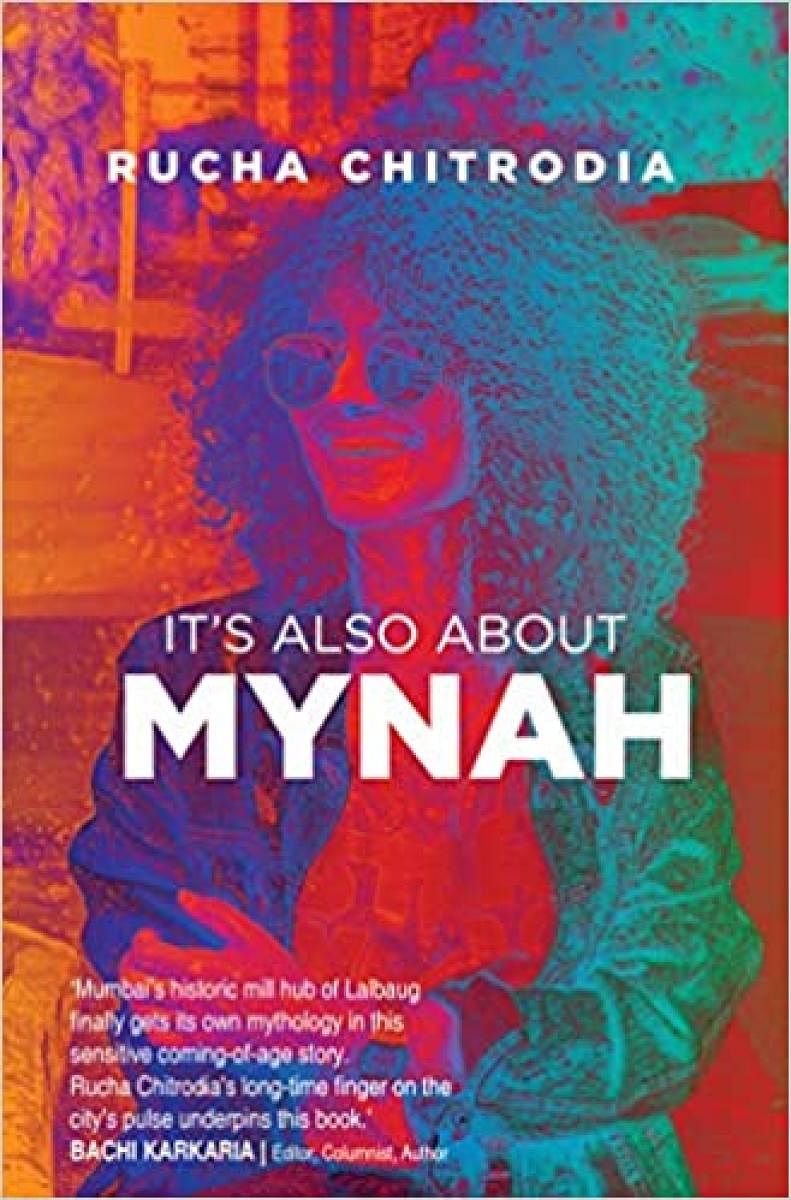

Joining their ranks is journalist Rucha Chitrodia with her debut work, ‘It’s Also About Mynah’. The title appears like a proviso, but one is probably needed, given the number of characters and stories that pass through this 200-page volume. However, Mynah, a ‘young woman with southern curls, milk chocolate skin and abnormally large and unusual yellow eyes,’ is a prime mover. It is her decision to get away from her over-protective father Gopala that prompts her to move to Mumbai for her first job. Her subsequent nervous breakdown, over the abrupt ending of a love affair, fastens the narrative to a plot that pirouettes around the themes of abandonment, struggle and healing. In short, a young woman’s coming-of-age tale.

Not only has Mynah’s boyfriend, the landscape architect Rohit, who once pursued her persistently, ghosted her, but in her distant past too, there is the spectre of her mother Gracy who left her (for a lover) when she was a three-month-old infant and never looked back. In Mumbai, Mynah works in an advertising agency. She is a paying guest in an apartment owned by a middle-aged divorcee, Aruna. The apartment complex is in Lalbaug, Parel, originally one of the seven islands of Bombay, and later, part of the mill hub, Girangaon that housed the textile mills on which the city’s prosperity was founded.

Ever-widening ripple

As the backstories of these characters unfold, they spread, in an ever-widening ripple, into the inner lives of others — Aruna’s ex-husband Subodh, his new wife Harsha, ‘self-assured with her old money swag’, Aruna’s maid Susheela, Susheela’s father-in-law Krishna, her son Suraj, her friend Kaveri and so on.

Likewise, Rohit, Mynah’s estranged boyfriend, brings his own labyrinth of kinship — a lacklustre father, Ram, who runs a coaching institute; a beautiful mother, Radha, who once, in her hometown Rajkot, had thought of marriage as an escape from poverty, but is ‘disappointed in the wimp of a husband whom she hit easily in frustration’ and spends her life, ‘imagining what could have been while lying on a bed that was too small for two.’

Readers looking for a conventional novel may find their expectations belied. While the key characters are fairly well drawn, the plot, as such, is not the driver of the tale. What Chitrodia presents instead is an alternate vision, via succinct insights and an assortment of montages, in which Mumbai’s former mill district is not just the backdrop but a character in its own story, as alive as all those who live — or once lived — in it, and from whose daily struggles it continues to derive its life force, the vibrant current that churns through its mazes and markets.

Glimpses of it are caught when in the maelstrom of traffic there comes a pause: ‘On the road where the taxi was waiting at a red signal several stores vended ready-to-wear festive traditional nine-yard sarees of Maharashtra and chaniya cholis from Gujarat for women aged zero to hundred and three, as a salesman was shouting to bring in customers.

Right next to it was an array of shops with stacks of cloth in a thousand colours, to be rolled up like ropes and wound around heads.’ Though this is a coming-of-age story, it is the author’s skill at social observation that makes the novel a worthwhile read.