It was a gloomy Saturday morning. Clouds hung hazily, and the sun seemed fairly apologetic, weak and mild, like a cup of tea gone cold. There was a crowd at the clinic. There was always a crowd at the clinic. It seemed like everyone’s favourite weekend activity was to go to the nearest clinic and be diagnosed with expensive ailments that required even more weekends to the clinics. The waiting area was littered with magazines, and the receptionist behind the desk looked suitably in command. It was here that she could dispense authority — it was at her discretion that those waiting were ushered in or out of the doctor’s room.

Posters adorned the wall — some warning you to consider the ill effects of unchecked diabetes and some others, rather incongruously showcasing a summer camp, a musical event in the local hall, and door-to-door delivery of groceries.

The Receptionist Goddess finally smiled at us and beckoned us to enter the doctor’s chamber. I kept aside the magazine, holding the door open for my Dad.

“Who is the patient?” the portly doctor beamed behind a massive desk. An orthopaedic surgeon was what he called himself. That title came along with all the credentials that he had acquired over the years. MBBS, FHRCS, MS — fancy alphabets that were tagged on to his name like the extensions of a comet’s tail. He patted the little bar stool next to him. I sat down in front of him, watching as my father lowered himself gently to the stool. My phone blinked green. A message from ICICI Bank assuring me that I was pre-approved for a loan of Rs 10 lakh.

“So, tell me, Sir,” the doctor asked. The Sir was only too eager. I listened to them converse as I fiddled with a glass paperweight.

The doctor’s diagnosis was swift. He didn’t even need to be a doctor to give this diagnosis. Wasn’t it apparent from the moment we walked in? Or rather, I walked in, and my Dad limped in?

“This, Sir,” he said, pausing as my father gazed at him anxiously. He had a flair for the dramatic, pausing in all the wrong places as he spoke.

“This pain in the knee is just old age.”

My Dad looked disappointed. No. He looked shattered. This wasn’t the diagnosis he wanted or expected. Old age was not even a diagnosis. It was a sentence. A life sentence.

He tried to smile at the doctor, hoping that he might be able to convince him to reverse that diagnosis. A shy, nervous smile.

“Old age? But, Doctor, the pain is just unbearable. I can’t even sleep at night! Every night, I take a sleeping tablet to just sleep. I can’t even climb the steps to my room. This isn’t just old age,” he pleaded.

“I understand, Sir. I will give you painkillers to manage the pain, but really, Sir, your knees are just fine for someone your age. It’s the age when your knees won’t be the same as your daughter’s,” he said, pointing to me, still sitting in the chair opposite him, across his impressive oak table. “Just don’t climb steps, Sir,” he grinned, as if that alone was the cause of everything.

My dad and I glanced at each other. I tried to smile at the doctor, out of courtesy, even though I hated him at that moment, for sitting behind that glass-topped table and giving this smug diagnosis. Logic told me that the man was being practical. He had no reason to be emotional. For him, my dad was just another patient. His knee was just another X-ray. Those knees did not speak to him the way it did to me. “Old age.” Those words echoed around, circles of echoes, bouncing off the walls of disappointment. Those words hung in that still room.

I shifted uncomfortably, the paperweight suddenly feeling all too heavy. A grisly skeleton was just next to me; its jaw open to the world, one limb askew. I longed to reach out and correct it, my sense of order wanting to impose sense even when there can be none.

My dad’s shoulders drooped. He had come here wanting a more drastic verdict. One with a fancy Latin name that we could Google later. But Googling ‘old age’ doesn’t have the same feel, does it? The doctor was done here, his eyes wandering back to the laptop that tracked his appointments. He wrote out the prescription for stronger painkillers, an ointment for external application, and then suggested that we take a few physiotherapy classes at the clinic. That was it. We were dismissed with a consultation charge of Rs 450. That was the cost of old age.

We drove back in silence. In my head, I could see the skeleton still from the doctor’s office — but it was wildly dancing now, even its limbs askew. Dancing to the wild patterns of time. The tick-tock, tick-tock DJ of time.

Since that visit, my dad seems to be ageing faster. He no longer asks me about going to America or a trip to Singapore. He worries about just the act of walking itself. I have seen him walk more than five kilometres every day for as long as I can remember. “I walk five kilometres! Brisk walk!” he would say to anyone who stopped him on the street. But now, he stops taking those walks.

Instead of walking that brisk walk, he now takes slow steps, tracing a straight line from one end of the terrace to another. When I ask him, he blames Bengaluru’s uneven pavements and potholed roads for not venturing out. Prod him enough, and he snaps. “I don’t feel strong enough,” he says. “I am 81 years old now!”

I bite my lips, swallowing the urge to say that this is all in his head. How can old age be anywhere but in our head? Isn’t that what they say? Age is a number? When does that number become weighed down like this?But my dad doesn’t want to listen. He goes out with the driver to Jayanagar and buys a walking stick to support himself.

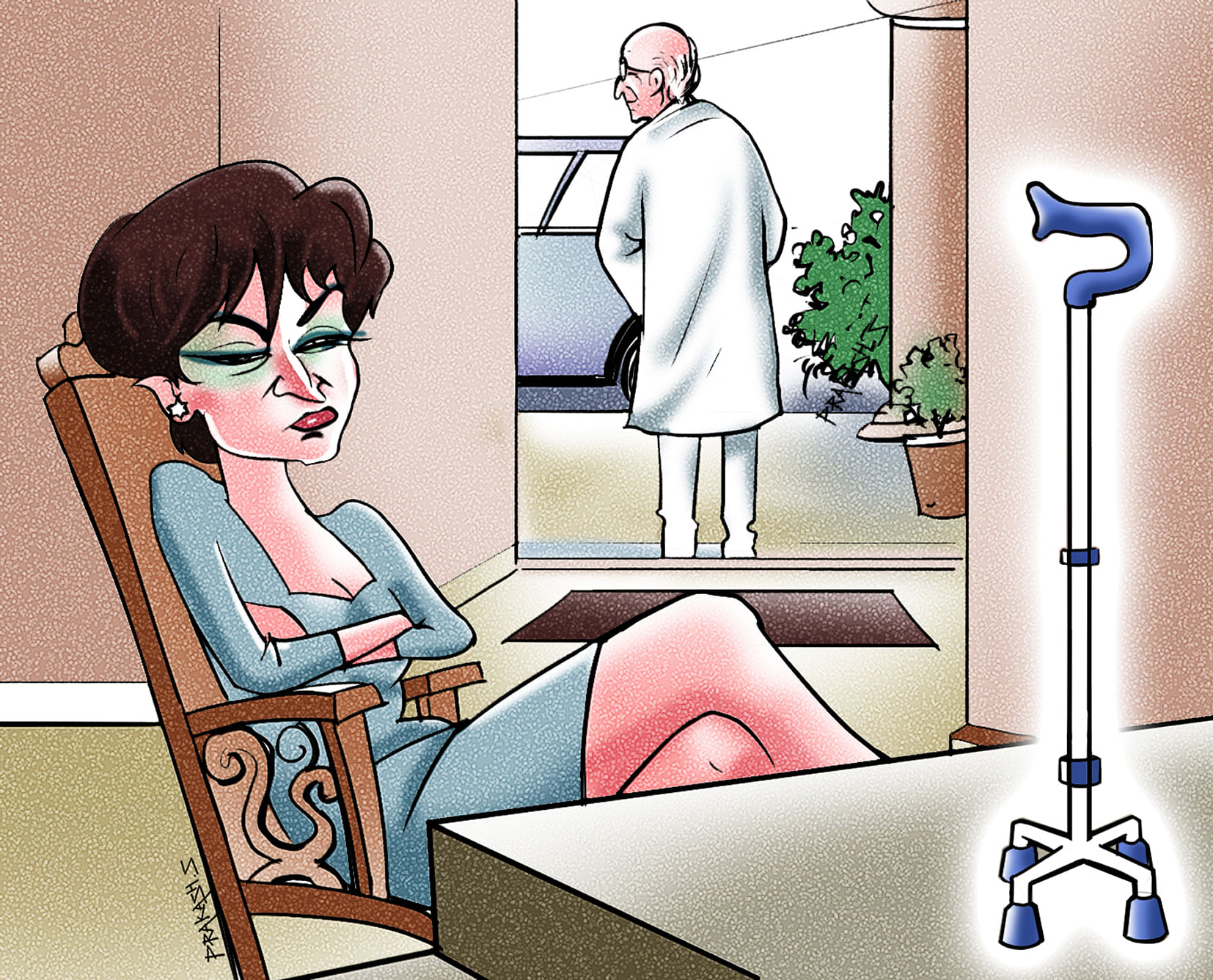

It’s not a romantic, wooden one such as you might have seen in movies. No. This is a plastic imitation with four legs. Almost as if the four legs are mocking the holder of that stick.

I hate that stick. I hate its smugness as it rests against the bed in my father’s room. I hate its four legs. I hate its plastic head, moulded to fit the palm of a person’s hand. I hate everything that is symmetric about it because it is killing everything that was and is symmetric in my life. I hate it more because it symbolises everything that I hate about life itself. That Time moves on, and we are inexorably clasped in its embrace. Lovers never do part. Till death. Of all my relationships, Time is the one that has been the most committed lover. I can leave all of them — my lovers — but Time won’t let me go. And now it has started to scream in my ear. An incessant siren of ticking moments.

These days, I wake up to the sound of that stick. And of Time. Plonk. Plonk. Plonk. The tap of it as my dad paces on the terrace outside my room, a dull echo seared into my brain. It is a sound I try hard to evade. Cotton plugs. Headphones. No matter what I try, I hear that sound even when I shouldn’t.

And then, I start seeing that stick every day. That gray head. The round plastic knob at the bottom. My dad would place it next to my bookshelf, resting arrogantly against my treasured books. Its insolence angers me even more. I rail at my father for its use.

“You don’t really need that! It’s just a crutch.”

My dad has very little patience, but in this, he is like a young father explaining to a petulant child. He repeats tiredly the doctor’s words. “Old age kano,” he smiles. “No. It’s not.” I can’t complete the sentence.

Every day, I wake up to that sound again and again. The sound of it is now an echo in my feverish brain. I am Edgar Allan Poe’s beloved coffin, lugging the dead sounds of the past, its weight heavier with each day.

That stick became a reminder of the futility of our days. Of Life. Of Time. Until one day, I decided that it could not stay. It had to happen. Now. Or never. And neither of those two dimensions exist. I smile at Time. I have you here, I think.

It is strangely another dank Bengaluru day. The monsoon has crept in and there is rain in the air. My dad is at my sister’s house. This is the only time I have to smuggle it out of the house, and into my car. My mom doesn’t hear me go out as I gently lock the door behind me. There is no need to involve more people in this, I resolve.

I drive away, down the street, down past the auto garage on the right and the driving school on the left. Past the old BET Convent and the biryani restaurant that no one really goes to. Past the Coffee Day. Past the BDA Complex. Past every single landmark that my dad has walked to over the years.

I don’t know where I am heading to. I don’t know how far I want to drive either. But my car seemingly drives itself. I go past the beloved coffee adda where my best friend and I have had many a cup of coffee, and then past the faded police station. I finally reach what I am looking for — a vacant plot — one of those that warn you that ‘This site is not for sale’, and splash the owner’s name in bold letters of pride.

This will do, I think. I snatch it from the back seat and then heave it into the overgrown cluster of weeds. There. I have done it! I have thrown the reminder of age; the reminders of mortality; the frailty of dependence. I have thrown away Time because I want my dad back.

I drive back, and I realise I’m smiling for the first time in days. I sleep soundly for the first time in many nights. And in the morning, I smile again when I wake up to the familiar sounds of squirrels screeching. But there is no plonk-plonk. I hear nothing that I dread. My mind is clear of my old lover.

When I step outside my room, my dad asks me about the walking stick. I feign ignorance. He looks puzzled but doesn’t ask more. No servants are blamed for its disappearance, and for some reason, my dad doesn’t replace that stick.

I don’t know when, but maybe it was then that we agreed that we would walk just fine without it. We don’t speak about it. We are not a ‘let’s talk it out’ kind of family. But we talk in other ways.

If he is in pain while walking, he doesn’t complain anymore. And if I see his face grimace in pain, I don’t ask.

Slowly, we slip into a routine that makes my life delicious in its comfort. In the morning, he wakes me up, and I walk outside with him through Bengaluru’s narrow lanes. We avoid the potholes and walk to the parks. We stand at times and watch as runners weave past us, lithe bodies glistening with sweat. We walk a few rounds and sit. And then we walk again. It’s a stop-start walk. Not at all a brisk walk.

At times, my dad leans on my arm for support. But most of the time though, it is I who is leaning on his arm for support. Because, you see, sometimes that is just what old age is.

Also Read:

An Appetite For Drama (The Second Prize-winning story by Pritika Rao)

The Silver Anklet (The Third Prize-winning story by Sharika Nair)