A decade ago, a break from journalism took me to a Montessori house of children as a volunteer, where I met Aditi, a beautiful girl with curly locks blocking her vibrant eyes. A child with severe developmental delays, Aditi was nonverbal and “able” to work with only a few materials in the environment. I set about teaching her to recognise the letters of the alphabet. I am not sure if I helped her learn, as I soon quit and moved on.

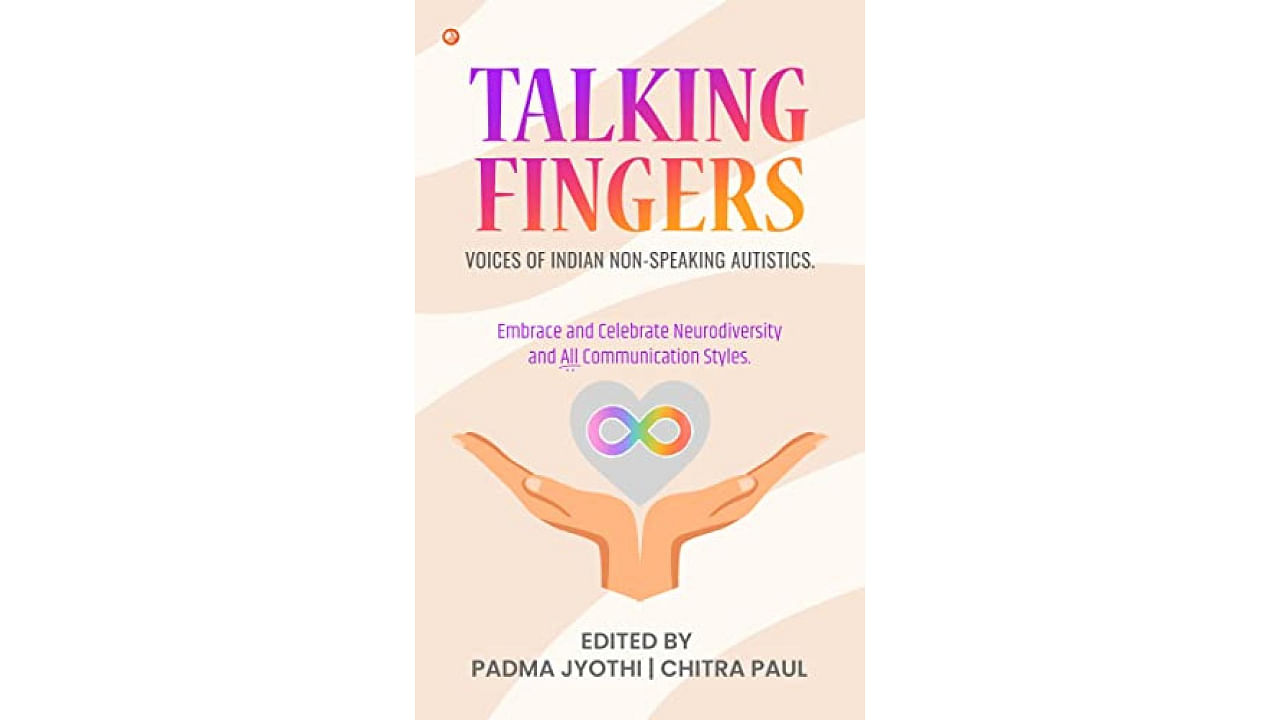

Today, I have a book in my hand, Talking Fingers, and Aditi is one of the writers. I am sorry I called her non-verbal. As I read her words in the book and on her blog, I realise how inappropriate the label is. She is mature beyond her years and profound. I am overwhelmed. I can see the beautiful mind behind those words, and I am in awe. The other 15 authors of the book seem familiar, like my own teenagers, for they talk about the world as they see it, and how they want us to see it.

Through Talking Fingers, its editors, Chitra Paul and Padma Jyothi, attempt to give voice to the voiceless. Both mothers of autistic children, the editors appear to be looking for answers to questions they themselves had while raising their children.

All individuals with autism have a “savant” skill. They are geniuses at music, math, and surgery, or they have a sixth sense. If this is what you think of autism, you are forgiven because that is the popular perception, thanks to movies, TV shows, and pulp fiction. Truth be told, they are all that and they aren’t. Just like the rest, some have average intelligence, average creativity, and below-average efficiency. They are us. If only we were willing to listen. Autism is a spectrum disorder, which means no two individuals with autism are alike.

“We wanted to bust the myth surrounding unreliable speakers — not speaking is not ‘not thinking or feeling,’” says Ms Paul, whose son Tarun Paul is also one of the authors. They are mothers and disability advocates determined to reveal the value that neurodiverse people can bring to our socioeconomic and political discourse.

The book is a brave attempt to introduce India and the world to the minds of unreliable speakers. It is a compilation of 16 writers answering 20 questions that range from when they realised they were autistic to how they want to be addressed. What do we call ‘them’: Disabled or a person with disability? Divyang or Angavikala? Their thoughts on neurodiversity and inclusion; how they see the world and how they wish to be seen; would they like to be addressed as “autistic” or “a person with autism”? Do they want to be cured of autism? Or are they comfortable in their own skin?

Isn’t that what we should be doing? Don’t give them what we think they want. Ask them and wait for their answer. Don’t assume.

Finally, here is a book that demonstrates our limitations in comprehending their ability. Our legislators, policymakers, and activists will do well to read the book and listen to more such voices. It will help make practical, relevant, and inclusive public policies.